Imperial (162 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

B

etween Phoenix and Tucson lies a quasi-Imperial zone which in the words of two climatologists

was mostly agriculture in the 1950s, but is now showing the effects of severe groundwater depletion, economic changes and widespread farm abandonment.

The farm abandonment desertification effect, by the way, is acronymically known as FADE.

FADE may cause up to one-third of the warming which would be brought about by outright urbanization.

FADE may also increase the dust content of the local atmosphere.

But just because farmers are leaving doesn’t mean that other thirsty entities cannot replace them. Back in 1927, Arizona’s bitterest rival had figured that out:

The relinquishment of agricultural land for urban use does not reduce the total water consumption as cities of fairly mature growth use water in amounts about equal to that required for irrigating the same area. The demand for water, therefore, can never grow less in southern California . . .

I wonder if the same might be true in Arizona?

By the century’s end, Arizona has “grown” sufficiently to gobble down her entire allotment of Colorado River water under the Colorado River Compact. Poor California!

Once upon a time, not long before the end of the nineteenth century, there was another Irrigation Convention in Los Angeles; and to there the delegate J. Rice of Arizona boasted, perhaps missing the menacing irony of his own words, that

in days that are forgotten in the history of Arizona there existed large canals, and large cities are now buried . . . that were . . . made possible only by extensive canals . . .

Arizona certainly needs her extensive canals! If only other states didn’t need them, too . . .

I went rafting down the Colorado River near Peach Springs, and my Hualapai Indian guide pointed at the white traces of waterline high above us and said in words as flat and wide as Yuma: That’s where the river used to be. Before Boulder Dam. Before California took all that for new cities and Nevada took the rest for Las Vegas . . .

320

And what might Arizona be doing with her share? Go to Boulder Dam, also known as Hoover Dam, whose curving, eerily white and dry wall, narrowing as it drops to a distant deck adorned with two powerhouses, looks down, so far down, to the dark brown-blue water whose expanding rings of white air rush up. That is how it looked in 2007. The Colorado went on, narrower. I cannot promise that some was not diverted to Arizona. Perhaps Nevada did sip away a trifle: I remember seeing that most beneficial of uses, the artificial waterfall at the MGM Grand Hotel (never mind the artificial river at the hotel New York New York, in which so many of the Strip’s shining signs are reflected). It might have been that California also dipped her fingers in and sucked them. And Arizona?

Go a hundred thirty miles south as the crow flies, to Quartzsite. Now you’re even with the entity I call Imperial. Yuma lies another sixty-odd miles ahead, but you’ll reach Laguna Dam first. On the Arizona side of the river, on the upside of Laguna Dam, beyond the skin of grass and cress, I remember that a sun glowed in the center of the still, still water—spuriously still, for white ripples streamed around it. This sun was the reflection of the sunset-struck nose of a rocky ridge in Imperial County; the greater part, which was shaded, had now nearly lost itself in the river’s greyness, so the peak shone almost alone, yellow-orange, made up of fractured rock; and as I watched and wrote, the water swallowed up ever more of the reflection, because evening’s shadow was creeping up the ridge; now the sun in the water was merely a crescent of gold; a moment later, it had gone to green shadow; all the orange was out of the sky now; the sky was white; like the sky in an old silver-gelatin photograph.

Below the dam, dark water flashed like time-scratched shale across the concrete basin and down between the wide-spaced concrete teeth to spew up in cotton-white clots, which then lost themselves in wider, more white-rippled darkness, then seeming to sink into the green plain of verdure.

Then it narrowed again, and narrowed . . . Perhaps Arizona drank a little bit.

One night on the California side, I gazed at the Colorado from under the Yuma bridge, studying the dull brown glint of it in the rushes. An Indian on the Quechan Reservation said that this was actually just a canal; from the map it seems to have been no less than the Reservation Main Drain. I crossed the bridge and entered Arizona. The Indian had been correct; the Colorado was a slightly wider stretch of slow brown water. As their creation song said:

This is my water, my water.

This is my river, my river.

We love its water . . .

It shall flow forever.

It shall flow forever.

Declining to shop at Yuma Citrus Plaza, I watched a six-locomotive train screeching slowly east of the Yuma yard; it was singing and screaming and rasping all at once, the broken bottle-bits on the sand not yet glittering in the winter morning sun. Then I went to the river where the small, paint-faded houses were; one even had a cupola. Soon I was at First and Gila.

Lieutenant-Colonel Emory, writing at the middle of the nineteenth century, describes the plain where the Colorado and the Gila meet as almost vegetationless except for

Larrea mexicana

and wild wormwood. (He was about six miles east of the confluence of the two rivers, both of which have shifted.) Here is my own description: Take Sixteenth Street, then go left toward San Luis, right to Quartzsite. You’ll see De Anza Plaza, Platinum Laserworks, the Inca Lanes bowling alley, and they all need just as much water as their counterparts in California.

Cocopah Casino—Stay on 95

.

Turn left to pass the various chain supercenters. Trust in Route 95. Then Yuma ends in flat green fields, with mountains off to the north; cross a winding blue canal, pass the Cocopah Casino; and the mountains and fields of Mexico will be ahead. Susy’s Plaza and Yuma Farm & Home Supply both use water, I suspect. Roll on, into Somerton, and after enjoying the sign for Paradise Water, feel free to observe the grey-green heavily odorous fields of cauliflowers going on and on. Then comes the wide S-turn of the highway between cauliflower and lettuce, and you’ve come into Gadsden. All across a long brown field, white buses and brown men in white sombreros are striding and bending in the dirt. White sprinkles of Colorado River water rise out of green and brown fields. And now you are entering Arizona’s last town, San Luis. A long flat pipe with frail side-pipes like fish-ribs lies across the dirt, and the horizon ahead is very low.

DO NOT ENTER

. Here’s Friendship Park! A Border Patrolman studies your face. Beside him in his vehicle stands a bottle of water. Next comes Mexico:

PUERTO FRONTERIZO

The taco shop in San Luis Río Colorado offers three bowls of salsa: blood-red with a hint of orange, carrot orange and deep green. Their liquid content derives from Colorado River water . . .

Chapter 166

WATER IS HERE (A VIEW FROM IMPERIAL) (2003)

W

hile singlemindedly attacking IID’s alfalfa and “low value” crops, Interior allows Southern California to fill its pools, water lush lawns, and frolic in water amusement parks.

Chapter 167

RAIN (2005-2006)

A

nd rain was smashing down on the greyness of Los Angeles and San Diego; even the Los Angeles River sometimes has water in it, reddish-brown with white foam, rushing past the graffiti on the gently slanted concrete bank—it could almost be the Seine!—the skyscrapers had become cloud-towers; silver puddles on grey concrete assured us:

It is simply needless to question the supply of water.

And in the Owens Valley, the smallish coagulations of clouds in the glowing blue sky graced snow-veined arid mountains, cottonwoods, sagebrush, tall greenish-grey grass. The orange-brown Bishop River had white foam in it. There were cloud-shadows on mountains, a huge golf course, a vacant lot which proclaimed itself the Property of the City of Los Angeles, pale leaves of cottonwoods, and then Bishop was gone. In the high desert, clumps of green trees were not ruined-looking. Big Pine was surprisingly green and lush, the Owens River a dark creek like the Colorado at San Luis . . .

South of Big Pine, the yellow-green desert went grey, balls of sagebrush yellowing and greying. Dust rose from what had been Owens Lake until Mulholland drained it. The steep dusty greenness of the Sierras did not change in the west, but the Whites went grey, yellow and blue under a rare rainstorm. Cool raindrops married dust in the hot air, and the temperature dropped in a couple of minutes from a hundred and one to ninety-five to sixty-nine . . .

Chapter 168

PROBATE (1901-2003)

Business . . . was his profession, but it was even more than a profession; it was the expression of his genius. Still more it was, through him, the expression of the age in which he lived, the expression of the master passion that in all ages had wrought in the making of the race.

—Harold Bell Wright, 1911

I

have never been cheated out of a dollar in my life,

but I’ve lost the odd dime here and there; oh, yes, Imperial turns my silver into quicksilver and it dribbles down, back into the sandy, silty earth. Barrett’s Boring Outfit sought oil in the 1890s and didn’t find it; we know what the great flood did to those two rival salt companies (their commercial skeletons must surely be festooned with whiteness now, in the foul depths of the Salton Sea). Next come the homesteaders, determined to profit from the transactions of agrarian democracy. Then the storekeepers and G-men commence operations. The Inland Empire creeps closer;

THE DESERT DISAPPEARS

, but where did it go? Where did Wilber Clark’s ranch vanish to? We find ourselves in the same position as the baffled subscriber to

California Cultivator

who writes (in 1920):

In the years past my father obtained patents to numerous property interests in this state from the Mexican government. On his death all of his property was willed to his wife. I have received no share in his property. Later there has been a fire in the house which has burned up all of the papers. I understand that my father was drunk when he signed the will. Much of this property was never probated. What is the position in respect to it?

How much is it worth? In other words, is Imperial rich or poor? That question could be answered in many ways. Should we find a per capita average income, or a median income, an income for field workers and another income for landowners? Must we, as everyone else does, separate Northside from Southside? Hopefully this book has helped you to make a determination, according to your own favorite category.

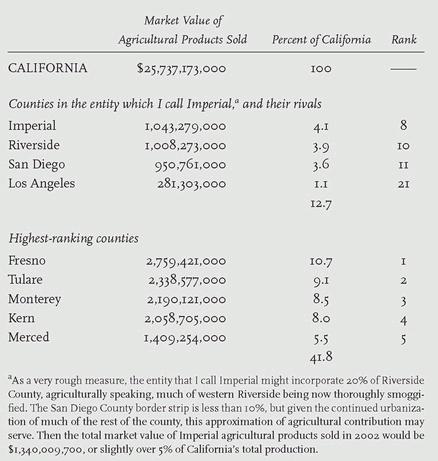

A question on which we can probably come to more agreement is: To what extent does Imperial continue to create agricultural wealth? Here are data for American Imperial:

CASH HARVESTS OF SELECTED CALIFORNIA COUNTIES, 2002

Source:

USDA, National Agricultural Statistics Service: 2002 Census of Agriculture, County Data (accessed online, 4/4/07).

In short, American Imperial’s accomplishments are hardly insignificant, but the boomers and boosters of early days, from W. F. Holt to Otis P. Tout, promised us more.

Were comparable data for Mexican Imperial available, we would surely find that the Mexicali Valley and the border strip produce a higher proportion of Baja California Norte’s agricultural yield. The Chandler Syndicate was quite aware of this; and did not trouble to buy much of the Marsscape beyond the delta.

So American Imperial is rich enough, and so is Mexican Imperial. But I met a Pentecostal pastor and his family on the road to Algodones. Those people made bricks, a thousand for thirty dollars. To wash, they swam in a canal of

aguas negras.

They said that they got so hot that many people they knew had gone to Jesus. They claimed to sometimes drink the

aguas negras.

At first I thought that I was not understanding, and kept pointing to the stinking black water in the ditch, and they nodded; perhaps they strained and boiled it . . .

How will their piece of Imperial be probated?

Chapter 169

SUCH A GOOD LIFE (2006)

You corn kernels, you coral seeds, you days, you lots: may you succeed, may you be accurate

—Popul Vuh, before 900?

T

eresa Cruz Ochoa and her husband José de Jesús Galleta Lamas were probably in their fifties but looked older. Both of them were grey, with strong reddish-dark hands. In their kitchen there were jars of candy, a poinsettia on the table, packets of American snacks in cardboard boxes. They had lived three kilometers south of the line in Colonia Borges for thirty years.