Imperial (166 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

With those words in my mind, I asked Lupe: Which side is more corrupt?

Lupe did not answer directly. He said:

La mordida,

it used to be that they never left you alone. But little by little it’s changing. They don’t harass you; they don’t ask for

la mordida

no more. A lot of people prefer to pay it, and not go to the fuckin’ court and lose a day’s work. See,

we

built the

mordida.

The people built it. So we’re at fault for that.

What is the main difference between life here and in the United States? I asked an old man in Tecate, and he replied: In the United States, life is easier, because people have a lot of help. For example, an old person here in Mexico, after seventy, they don’t get any help. Moreover, here if you didn’t work, you won’t get anything. But on the other hand, it’s better to live in Mexico because there’s less pressure. Over there you have to work all the time; you have to get up early; if you want to stand in the street and wait for a job, you can’t, because the police will investigate you. Over there, everybody works, and whatever you earn, you end up just paying your rent with it.

Again, what about this freedom that Mexicans kept talking about? Just west of Mexicali’s Colonia Chorizo, and in sight of the border wall, I remember a woman of the garbage dump: long-fingernailed, her smile sawtoothed and crescent-shaped like a citrus pruning knife

circa

1930. A girl of seven or eight years was also playing in those stinking heaps. When my interpreter and I asked to speak with her, the father, good defender, encouraged our departure with a machete. These people all survived; they stank but seemed vigorous; I doubt that they paid taxes. They were free, weren’t they?

We live more freely here, said a government worker in Colonia Santo Niño, but on the other side (meaning Northside) there are many Mexicans, and you won’t see them taking an empty can and throwing it into the street. The instant they cross

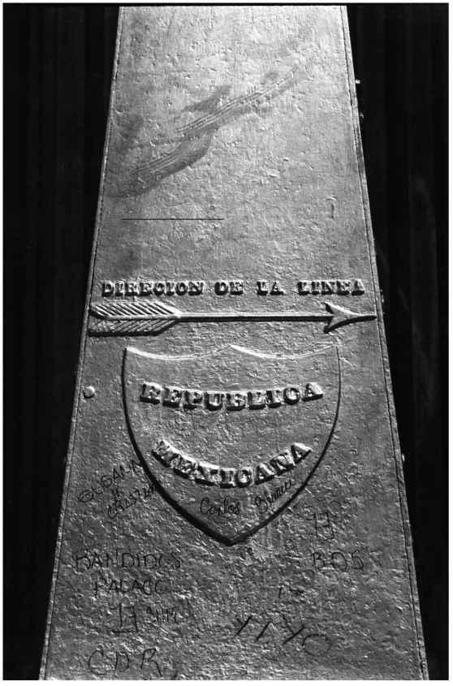

la línea,

they do that. Right over here, it’s all garbage.

The border may indeed be unfortified,

wrote Ruben Salazar in 1970,

but it separates two people

[

s

]

who created the Mexican-American—a person many times tormented by the pull of two distinct cultures.

But, thanks to the Spanish Conquest, might not bifurcation be a part of

all

Mexican-ness? The syncretic Virgin of Guadalupe rushes back into my mind. The pull of that latest Spain, Northside, now sucks

pollos

out of Mexican villages everywhere. One Mexicana said to a biographer of Cortés’s native mistress:

Malinche has always been venerated, here in Tlaxcala.

325

But perhaps we have been punished for this. People say that is why all our young men leave. They go to the capital, to the north, or even worse, to the United States . . . It’s a curse, they say, . . . the allure of foreign things.

Gringos hoard their ill-gotten riches; Southsiders expropriate. The existence of such stereotypes, which contain some truth, explains why it is that in Mexican Imperial we find such folk saints as the rapist Juan Soldado, the bandit-revolutionary Pancho Villa, and the robber Jesús Malaverde, now the patron of narcotraffickers; while American Imperial has proffered such exemplars as W. F. Holt, also known as Jefferson Worth, Minister of Capital; nor should we forget his fictive daughter Barbara Worth.

Mexican-ness partakes for better and worse of localism.—Josefina Cruz Bermúdez said to me: I am from Mexico City and I only know Tecate. It’s the same in other places. You only know your own neighborhood.

As for me, I know many neighborhoods, or think I do. Perhaps I know none. Does that make me an American?—Where am I from? I was born in California; I think of myself as a Californian; but when I meet an Oregonian or a New Yorker, in my mind our similarities far outweigh our differences. We are Americans first and last. Meanwhile, in the late 1920s, Paul S. Taylor shockingly

found no recognized word or phrase all-inclusive of the various groups of persons of Mexican ancestry in the Southwest.

They are all Mexicans to us, of course.

I asked the government worker in Colonia Santo Niño: In your opinion, when somebody crosses the border and decides to live over there in the United States, how soon does he become an American?

On the north side, people who live there are North Americans. On this side there are Latins. Before, there were patrons who would sponsor people to come across the border and would get their papers in order. When they live there three years, that’s in my opinion when they stop being Mexicans and start becoming Americans. There was an American governor who said that.

Well, I thought, why not?

THE UNKNOWN

Working hypothesis: To be American is to cross the ditch or not, but in either event to remain unchanged by the other side. To be Mexican is to cross the ditch and be changed, or to be prevented from crossing the ditch and therefore to be changed. (I would never characterize them as hostile, objected the old pioneer from Heber, becoming hostile.) Is there anybody in Mexico, even in the remotest mountain village in Chiapas, whom the reddish-rusty shimmer of the border wall fails to reach? Mexico means Mix-aco; everything and everybody is mixed like a produce market’s red, white and green: blackish-red chili pods heaped like a mass of curve-clawed crabs, white garlic and red beans splendiferously abundant in their various tubs, emerald nopal lobes in a boy’s hand as he whittles away their spines with a dreamy smile. (I give a Mexican a dollar and his face lights up: Ah! A green peso!) At Algodones, just south of the Quechan Reservation, the line of cars bound for the United States waits for blocks and blocks, while a loudspeaker shouts into Mexico:

All right, everybody, mrphh mrphh mumpph.

Algodones possesses taco stands; Algodones offers serapes for sale in U.S. dollars (once, in Niland, almost in sight of Leonard’s mountain, the old lady whose child owned the hotel let me pay for my room in pesos, once and only once; that was an exotic experience). Algodones bears many English-language signs for the better assistance of tourists. In front of one of them a man is hacking up a fallen palm tree. And down below him, on the banks of the Río Colorado, a man in a baseball cap which advertises an American fast-food chain sits all day on a rock surrounded by algaed water whose breath makes him feel a trifle cooler; his beard grows longer; he keeps thinking about invading Northside, but he feels discouraged. He treasures a single cigarette in the breast pocket of his shirt. He crosses his wrists in his lap, deciding what he should do. This side or the other side of the ditch?

Now I hear the people smugglers are getting so brazen, now they got the Humvees with the guns mounted on them.

MORE UNKNOWNS

I “love Mexico.” What does that mean? Would I live there? Only if I had money. Would I marry a Mexicana? Undoubtedly. Would I worry about crime there more than I do now? Yes, because more people in Southside are poor, and my white skin asserts me as a Northsider.

326

Would I be more free in Mexico? I honestly believe so. Would I be happier? Are

they

happier? Not particularly . . .

Mexico is the street prostitute Liliana, who keeps reminding her clients: I’m a poor woman.—In the hotel she’s all enthusiastic: I want to suck your dick! I need to suck your dick! Please let me suck your dick! and then: I want to be your friend! and then: I want to know all of life, so I want to be a serial killer. And she keeps staring at you with her crazy eyes when she repeats this last thing, so that it’s legitimate to wonder whether she’ll suddenly caress your throat with a razor. Fertile, sincere and occasionally menacing, that’s Liliana; that’s Mexico.—I’ll be back, she says. She adds: But you said you had no money and you’re staying at this expensive hotel! You lied to me. I’m going to wait out in the street for you all night. What do you really want? Just tell me the truth. I’m a poor woman; I’ve got to go now; I’ve got to work all night.

America is—what? America is me. I come to buy Mexico’s time (I can’t even remember anymore whether I slept with her). I want to be her friend, and then I want to write down my notes to put her in this book. What do I really want? Of course I lied to her; if I’d told her how much money I had, she would have robbed me . . .

I’m generous, I tell myself. I always tip José López on top of what I pay him; I invite him into my room to take a shower; he washes his stinking clothes in my sink. I buy him a meal. Then what? I put him in my book and stroll over to Northside, where he cannot go except at extreme risk. Who is he to me? I worry about him. So what? He’s a poor man; he’s got to work all day.

Proud, sad, yet watchful; portrayed with a downward gaze; hooknosed, with fleshy lips; simply stylized, as Orozco’s creations usually are, with bright light on his cheekbones, nose and chin, most of the forehead darkened by inky hair, the rest of his profile in shadow—this gouache is called “Study for head of an Aztec migrant.” Who is he to me? Who am I and who can I be to Mexicans, who have enriched my life beyond my most greedy and romantic calculations?

PART THIRTEEN

INSCRIPTIONS

Chapter 175

STILL A MYSTERY (2003)

Names Appearing in Black Letters

IN THIS DIRECTORY are the names of people who ACCOMPLISH THINGS and are entitled to favorable consideration . . . The publishers are honored in thus making them better known to the public.

—Imperial Valley Directory (1930)

I

opened the newspaper and read:

JUDGE ORDERS FULL WATER ALLOTMENT

and

TERROR ALERT ORANGE: Calexico: High risk level may cause delays for border-crossers.

That was on page one. On page two I read:

Holtville readies for Schwingfest

and

Man pleads to smuggling ring in S.D.

(a human-smuggling ring, of course) and

County marks end of phase 1

and then, at the bottom of that page,

Identity of dead man found still a mystery.

The identity of a dead man found floating in the All-American Canal west of here Monday was still a mystery due to the advanced state of decomposition . . . According to the deputy coroner, it was not thought the man was trying to enter the country illegally at the time of his death due to the way he was dressed. The man was reportedly wearing a T-shirt and jeans in good condition, black dress shoes and a Mexican military trouser belt.

That was on Wednesday. On Thursday, the front page said:

U.S. INVASION OF IRAQ BEGINS

and page two said:

Filth an ongoing problem, merchants say.

I guess that the identity of the dead man was still a mystery, since the newspaper didn’t mention him. Well, after all, how could we be expected to keep track of every death? On Tuesday a lady in the three hundred block of Chisholm Trail in Imperial had discovered a dead bird in her back yard.

An animal control officer was sent to pick up and dispose of the carcass.

That was in the

POLICE BRIEFS

section of another newspaper.

On Friday, the brand-new “Liberation of Iraq” section began with a quotation from the President, and then on page A2 the most dramatic item of local news was

El Centro asparagus thief sought.

The identity of the dead man must have still been a mystery.

I missed Saturday because the newspaper fooled me. Usually it didn’t appear in the vending machines until midafternoon of its day of issue, so I foolishly waited until Sunday morning to get Saturday’s news, but it turned out that Sunday’s paper was already there. Anyhow, on Sunday the front page said:

HALFWAY TO BAGHDAD

and page three said:

Broccoli cartons latest stolen crops.

I can’t honestly claim that anybody else had died on the international line; and no doubt I am bigoted; no doubt I tend to think of Imperial as being more correctly represented by the newspaper some months later, which not only reported a

Body found in mountainous area

(a suspected illegal in Mountain Springs Grade) but also bad fishing on the Salton Sea (Ray Garnett, in whose boat I had motored down the lower reaches of the New River, informed me at that time that algal blooms had prevented him from catching a thing for three weeks now), than by

Broccoli cartons latest stolen crops,

which downplayed the gloom and doom, recasting Imperial as nothing more or less tragic than the epitome of provincial dreariness—straight out of Chekhov. Illegals didn’t die every day in Imperial,

327

and the Salton Sea wasn’t always terrible. Meanwhile, the identity of that dead man continued to be a mystery.