Imperial (169 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

Far below, the Mexicali Valley glows like a sulphurous sun.

333

Here at Rumorosa the plateau is especially beautiful just before dusk with the mountains low like purple crystals at the edge of it, and the few cloud-puffs touching it and everything gold or tan or purple-shaded as one goes eastward into that stunning golden light.

The road from Tecate down to Mexicali is called the Cantú Grade. Ahead one sees a maze of rock, and then suddenly the pink and orange cavern of light where Mount Centinela basks and many

pollos

cross, while the violet light gradually turns silver.

From Mexicali the clean, wide, green and brown grids of the Imperial Valley are best seen from between the slats of the border wall while one waits to cross, anticipating constellations of white birds in green fields, mirages on the almost-empty highways (emptier than Mexico), and ever so many longnecked birds.

(Once upon a time, coming into Northside past the long line of Mexicans with papers, I met the stern, tired, bald personification of American paternalism, who questioned me, then curtly, shruggingly gestured me out of his sight. Speechlessly they X-rayed my notebook, and I emerged from the big door crowned by portraits of Bush and Cheney; here was Calexico, whose streets were emptier and more orderly than Mexicali’s. There was some English spoken but the people looked mostly the same as in Mexicali. I heard the clink of the turnstile through which people depart the United States. A plump Mexican-American girl with a bun of brownish-blonde hair sat on the sidewalk in front of the burger chain store, smoking a cigarette. A Border Patrol wagon rolled briskly by. Then all fell still. After using the telephone, I went back to Mexico. How easy it was!—But it used to be even easier.)

Reader, shall I tell you what makes Mexicali unique? I know, because I have asked Rosa Pérez in the Park of the Child Heroes this very question, and she replied: For me, there are no boundaries. All is God’s. All is the same. The woman is the crown and the man is the creature of the earth.—And here the old lady began to sing:

From cup to cup you ruin your life, drunk for a woman.

But let us push on through the

ejidos, colonias

and desert of the Mexicali Valley’s three thousand square kilometers. (As it happens, the line itself follows squiggly rivers of shadow, DRIFTING SAND NEXT 7 MI at Glamis, then the new world of the dunes, their domes and facets so sharp in the evening, white and blue; they open up, salmon-colored in the dusk, with the mountains of Mexico a series of pink and blue jewels on the horizon.) Halfway between Mexicali and Algodones, cotton bolls and hay bales adorn a green October field; children play in a spilled truckload of cotton while their elders clean it up: three thousand dollars’ worth.

San Luis Río Colorado is longer and lower than the heart of Mexicali, the square blocks of bars and restaurants weighing down the pavement, like the smell of disinfectant in the Motel California, which is also the Hotel California. On the old-style wall, which is not see-through strips of landing mat, the top strip angles into Northside palm trees, whose bottoms have been artfully whitewashed. On the Mexican side, the wall has been painted with, for instance, a profile of Nefertiti, a map, hand-painted advertisements.

... And they come very very close to me, the tall tattooed boys, staring into my eyes and asking why. When I try to tell them that I am writing a book, they become contemptuous; because to them it is just wall, somewhere between rust-colored and tan against the grey dirt. The sky becomes a lovely yellow-orange over it; and farther away from town the wall is graffiti’d again with a skull and then it goes just blank, blank, a border and then more blankness, then a dairy cow corralled up against the wall.

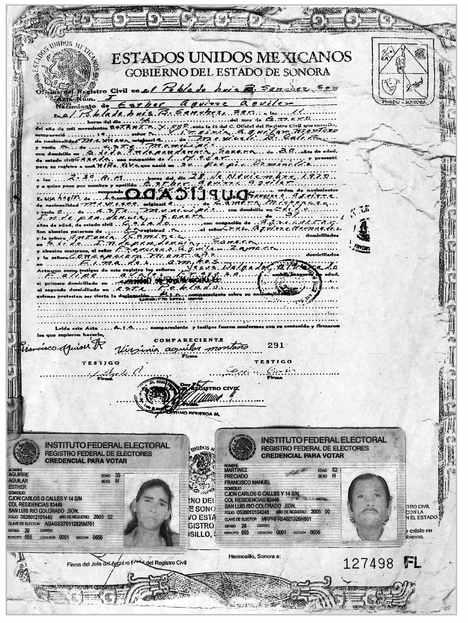

In this city called San Luis Río Colorado, Francisco Manuel Preciado Martínez weeps on a park bench ten minutes’ walking from the line itself. He comes originally from Hermosillo.—I got here in 2004, he says. This is where Immigration brought me from Seattle, Washington.—And he shows me a government document which bears a photo of his wife.—They took her, he says, bursting into tears.

Who took her?

I invited a friend to stay in my house and he took her. It happened on the twenty-third of October of this year.

When was the first time you crossed the border?

In 1963. Into Yuma, Arizona. From here. I walked, he said, weeping, because I did not have money. It took about three days. I saw many things but I was very hungry. I just remember that I was thirsty and I was hungry. It was in June and it was very hot. I wanted to work, he wept, wiping his eyes.

How did you know where to go?

I just went. I walked in the day and in the night. I got to Yuma and jumped a train and went to Los Angeles. That was the first time I had done it but some other people had told me how to do it. The train was stopped and I jumped onto a car. It was a boxcar with three holes up top. Nobody could see you. I was just lifting myself up and looking out of the hole. The train ran alongside the freeway. It took eighteen hours. It was right near Los Angeles, Puente Los Angeles, fourteen miles from Los Angeles. I went there because I wanted to work in Washington; I had a good job over there. I knew I would have a job with the Boeing Company, because I could fix airplane parts. So in Los Angeles I went straight to look for work. I went to work in Brooklyn Avenue, East L.A. I slept right there where I worked. They gave me some food and a place to sleep. It was like a tortilla factory and they made chorizo, carnitas, bread. I got paid sixty dollars a week. It was a little room where I slept. Fifteen people were sleeping and working there. Everyone was illegal. I saved my money and went to Washington. They were sad because I worked very hard. A man who was already headed that way, I paid him and he took me in his car. It took thirty-two hours. I paid him a hundred dollars. He dropped me off at the rescue mission on Second Avenue. I went to a placement company and put in an application to work in Alaska. Boeing called me after three months in Seattle, Washington, he says, sniffling, his face bright red, his left hand raised as if he were swearing some oath.—I was in Seattle for three months looking for work and then in Alaska for six months. In Saint Paul, near Russia. It was a contract job in a fishing boat. They paid twenty-five dollars an hour. And then I completed my job and flew back to Seattle on the company plane. When I came back to Seattle, I could afford an apartment. I kept in touch with my boss. And after two months my boss got me the job with Boeing. I had worked with a man from Missoula, Montana, in 1980. Through that friend I met the boss. I started working at Boeing in 1990. Then somebody reported me to Immigration, and here he burst into tears. Boeing paid me a lot of money.

A lot of money!

he shouted. I was working and then the next thing you know I was in an airplane. They grabbed me, just like that. They took me in the plane to Chihuahua. Then I hitchhiked here.

Police report on missing wife, received by WTV in 2006

He is fifty-two, and his wife, whose name is Esther Aguilar Aguirre, is thirty-six, according to the color photostat of the police report that he hands me. I buy him a meal and give him money; soon he is in the street getting drunk with his friends.

Pleading for more money, he follows me all the way to the wall, which is painted and rusted, aloof behind its row of whitewashed palm saplings, its fence and yellow curb so very still in the Sunday heat. After a longish time, a fat blonde comes, dragging her steps, with a plastic bag of groceries weighing down her haunch of an arm. This is the first street, where Mexico begins; it’s vitiated and poisoned by the wall, or maybe just defined by it.

Coming out of San Luis Río Colorado into Arizona, the twenty miles to Yuma will be wide, perfectly furrowed dirt, with sky-blue reflections in each irrigated furrow—oh, Northside’s wide highways are shockingly different—

Chapter 177

SUBDELINEATIONS: MARSSCAPES (2004)

Could the gray-green areas in an otherwise reddish disk be vast, plant-filled oases sprouting forth from a global desert? And was it possible that those remarkable straight lines some astronomers perceived were canals created by an advanced civilization?

—Astronomy, 2003

P

ossible indeed! May I tell you why? Because

WATER IS HERE

!

To tell the truth, the most Martian place of all isn’t Imperial, although I grant that Signal Mountain is somewhat that way, especially mornings and evenings when it glows grey-red; but if you ascend high enough to gaze down into Northside, then you’re compelled to believe in aliens, because here’s an onion field; there’s a haystack; they add up to vast, plant-filled oases sprouting forth from a global desert!

We need have no fear that our lands will not become better and better as the years go by.

That’s what the Martians say. But wait a minute! I’m from San Diego; I don’t believe in Martians. Better to enjoy the Marsscapes of San Diego County; for instance, near Split Mountain in the Anza-Borrego badlands, not far from Ocotillo, there’s a long wide streak of Martian daylight across the shadowed bluff; everything is a shard; red rocks crouch on tanscapes which appear to be made of sand but bear one’s weight without even leaving a footprint, like the superfrozen snow of the high Arctic; here on Mars the weird trees are invaders; the bursts of yellowheaded bushes out of fractured rocks shouldn’t be here; when from far away a human’s grating footsteps sound, that isn’t natural. Reddish-yellow shards of daylight lie in fractured marriage with the shadow.—Oh, man, like, see, this would be so cool to hike up to that mountain up there! cries Professor Larry McCaffery on 4 November 2003, smoking his last cigarette ever, the absolutely last before he quits.—And you can imagine the view you’d have!—Larry, also known as Lorenzo, at least when in the alien world of Mexico, takes two steps away while I’m scribbling in a notebook, and then before I know it he’s at the top of a ridge! It must be that low Martian gravity. This is the place where Imperial gets crumpled up against the sky.

One reason this must be Mars is that the sky is so dark and cloudless. Leaning strata of sand, fossilized oyster shells, these signifiers of long slow change almost seduce me into imagining an epoch when Martians actually existed, in which case they would have been worthy of my consideration. Oh, give me grooves, wrinkles, yonis and clefts in the rock instead; that way I don’t need to recognize anything but the pleasure principle! (What about freckled granite in white sand? I see it but I won’t acknowledge it; it’s not Martian; it hinders this subdelineation.)

I’m from San Diego. Imperial’s more remote than Mars to me. I need the water, so I’ll take it. A few million years from now I’ll explain to my friends:

Gone are the oases, canals and cities . . . But the abode of Mars as the abode of hostile aliens lives on.

“WARPED AND CRAWLING THINGS”

Reader, what is Mars to you? To me it’s simply Otherwhere, but most science-fictioneers refine that definition at least enough to convey a sense of desiccated deficiency. After all, who dares to claim the desert’s superiority to the oasis? A proper Marsscape, then, invites the following clichés:

harsh, dangerous, red, alien.

Never mind cold and thin air, which characterizes no part of Imperial excepting a few mountain-scraps around Tecate, the Sierra Cucapah, the Chocolate range; we know quite well the temperature appropriate to our area of study! Once this latitude has been granted, almost any science-fiction opus set in a dry place will qualify as an Imperial Marsscape—for instance, Walter M. Miller, Jr.’s bitter parable

A Canticle for Leibowitz,

which takes place on Earth.

Gone are the oases, canals and cities,

because nuclear war shattered and poisoned those.

The abode of Mars as the abode of hostile aliens lives on.

Who are they in this case? Mutants: piebald men, two-headed women, freaks and monsters with human souls, which is why the Church prescribes their raising and nurturing, so that they’re called

the Pope’s children. Their ranks were continually replenished,

we’re informed,

by warped and crawling things that sought refuge from the world.

They kill poor Brother Francis with an arrow between the eyes, because they’re hungry. Let’s call them Martians, unless you want to think of them as illegal aliens. The Martians in H. G. Wells’s

War of the Worlds

possess similar habits to the Pope’s children; they’re even scheming to sneak across the darkness of the interplanetary border and land here!

Now I hear the people smugglers are getting so brazen, now they got the Humvees with the guns mounted on them. They got laws on the books and they’re not being enforced.

All head and no digestive system (they live by injecting themselves with human blood), causing the narrator to muse over

the actual accomplishment of . . . a suppression of the animal side of the organism by the intelligence . . . Without the body the brain would, of course, become a mere selfish intelligence, without any of the emotional substratum of the human being.

Miller’s Martians are, on the contrary, idiotic bodies bent on their own needs and greeds; while the selfish intelligences he imagines are scientists and politicians who rebuild the world out of its postapocalyptic Dark Age in order to launch another nuclear war. Only the monks and abbots of this Marsscape recognize others’ humanity—or their non-Martian-ness, I should say. Wells again:

Those who have never seen a living Martian can scarcely imagine the strange horror of its appearance . . . There was something fungoid in the oily brown skin . . . Even at this first encounter . . . I was overcome with disgust and dread.

In the end, we almost feel sorry for his Martians, who are all carried off by terrestrial pathogens; the last one wails a solitary amplified ululation within its metal spider, then becomes bird-food. But until they perish, their otherness remains coolly malevolent. This is why Miller’s vision must be considered superior to Wells’s, at least from a standpoint of empathetic accomplishment. Who are we to judge the Pope’s children? A dying abbot, half crushed in a nuclear blast, receives the Host from a woman with two heads. The younger head, named Rachel, has taken over the woman’s body, and it becomes vigorous, supple and beyond the human exigencies of bleeding and pain.

He did not ask

why

God would choose to raise up a creature of primal innocence from the shoulder of Mrs. Grales . . . One glimpse had been a bounty, and he wept in gratitude.

Then he finishes dying, as does the Earth. Earth becomes Mars—I mean Imperial—so thoroughly that even the Martians are dead! In the words of still another science-fiction writer, J. G. Ballard,

the blighted landscape and its empty violence, its loss of time, would provide its own motives.

In other words:

Though large parts of this may certainly be reclaimed by the waters of the Colorado, we are not at present recommending our desert.