Imperial (167 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

On Monday the front page said:

U.S.: ‘DRAMATIC’ PROGRESS SEEN

in Iraq, an extremely helpful bit of news whose accuracy was underlined by

Iraqi resistance slows advance.

Page seven reported:

ASPARAGUS: MARKET SLIGHTLY HIGHER.

On Tuesday the front page said:

WRITTEN ORDER ON IID SUIT RELEASED

and

SANDSTORMS THWART AIR MISSIONS

and

Border Patrol reports fewer apprehensions.

Page ten noted that five illegals were burned alive in a controlled burn of a sugarcane field near the border; maybe it wasn’t so controlled after all, or at least I hope not; anyhow, it happened not in Imperial but in Raymondville, Texas; I must have put it in this book by accident

.

On Wednesday nothing at all occurred. I read the newspaper twice, because nothing was taking place in my life, either; all I could make out was that our military continued to make great progress.

On Thursday the front page said:

U.S. VOWS TO INTENSIFY ATTACKS

and

GUARDS POSTED AT IID DAM, NERVE CENTER: TERROR THREAT:

Beefed-up security aimed at protecting water, power facilities,

probably from the broccoli-carton thief

.

At the bottom of the page, I learned the following:

One dead, 18 hurt in rollover after blowout.

WINTERHAVEN—An unidentified man was killed and 18 others injured when a stolen vehicle suspected of carrying undocumented immigrants overturned near here Wednesday night when one of its tires blew out.

So now it had been a week and a day, and I had to face the likelihood that the name of the dead man in the All-American Canal would continue to be a mystery.

HOLTVILLE

Is this such a terrible thing? Someday, reader, you and I will be forgotten. In this regard I’m reminded of a certain haunting phrase by George Eliot:

unremembered tombs.

How many should we remember?

Leave the dead to bury the dead,

said Christ, in part because there are so many dead! On 12 July 1853, Señor Dolores Martínez of Los Angeles is

found shot by zanja.

A

zanja

is nothing more or less than a water-ditch, the All-American Canal itself being just another

zanja.

Who might Señor Dolores Martínez be to us? His identity will continue to remain an everlasting mystery. Moreover, in 1853 somebody died by violence pretty much every day in Los Angeles. So even if we could somehow come to know this murdered man, what about his three hundred and sixty-four-odd compatriots?

Once upon a time in Imperial—on Friday the eighth of May, 1914, to be exact—the former deputy county clerk, Miss June Bagby, now residing in San Diego, was

reported to be suffering from a slight indisposition, though nothing serious,

and James Hamilton of the Enterprise Grocery approached recovery from having inhaled a fly while being shaved. Aren’t these facts history? Don’t Miss Bagby and Mr. Hamilton deserve to be remembered just as much as Señor Martinez, even though they failed to accomplish anything as dramatic as dying right then? As the Women’s 10,000 Club used to say,

the aim, if reached or not, makes great the life.

And what if there exists no aim whatsoever, or if we’ll never discover it?

In the county of Imperial, in the city of Imperial,

1 mi n SP track,

local registered death number twenty-eight occurred on 29 July 1924. Full name:

John Doe unknown Mexican.

He was about thirty-eight, and his occupation was

apparently laborer.

The cause of death was

Heat Stroke found dead on

Southern Pacific

track 1-mi no-Imperial.

His birthplace, parents, etcetera, were all

not known.

They removed him to Mountain View Cemetery in El Centro.

328

Local registered death number twenty-nine occurred on 31 July 1924, the place of death being identical with Albert Henry Larson’s two years later, namely,

7 miles N West.

Monica Gordins,

female Mexican, single,

three months old, name of father unknown, maiden name of mother, if I can read it,

Yolda Yolda,

died of heat prostration and was buried that same day at Mountain View. Did the baby get no funeral?

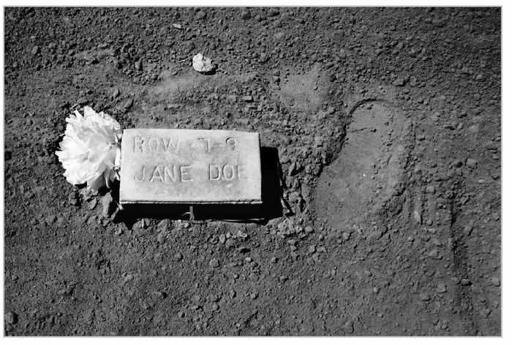

So much about those unknown lives will never stop being mysteries. But for mysteries within mysteries, visit the unremembered tombs of Holtville. I suppose that the dead man from the All-American Canal has now taken up residence there. Perhaps they allowed him to keep his black dress shoes.

Go through the green grass beneath which entitled people are buried. Pass beyond the immense hedge and then the shrubby border proper to the furowed naked brown field with the knee-high white crosses imprinted with the pious lie

NO OLVIDADO

, not forgotten; on each there is a paper flower and a cup and saucer. I have not forgotten

ROW 7 24 JOHN DOE

; nor have I forgotten

JANE DOE

beside him; I recollect

ROW 7 10 JOHN DOE

and

ROW 7 11 JOHN DOE

, not to mention

ROW 7 12 JOHN DOE

,

ROW 7 13 JOHN DOE

,

ROW 7 15 JOHN DOE

,

ROW 7 17 JOHN DOE

, all of whose identities remain mysteries, and then, when you are ready for them all to be

OLVIDADO

once more, why, return to the front lawn of Terrace Park Cemetery, where the dead bear names, lying across the highway from a hayfield of whirling sprinklers.

RAG ENIGMAS

In 1531, Juan Diego Cuauhtlatoatzin (“He Who Speaks Like an Eagle”) received miraculous winter flowers and wrapped them into his mantle. He carried them to the skeptical Bishop, and their magic left an image of the Virgin of Guadalupe on the very fibers of that garment. Sometimes in Imperial I think of that when I see the abandoned garments of

pollos

beaten down into the hardpacked desert until they’ve become flat stones. Whom did they belong to? That’s a mystery. (Officer Gloria I. Chavez, U.S. Border Patrol:

I think we all feel sorry for ’em.

)

JOSÉ LÓPEZ’S FUTURES

The fact that

the identity of a dead man found floating in the All-American Canal west of here Monday was still a mystery

reminds me that that veteran illegal border-crosser, my friend José López from Jalisco, committed one of his sixteen immigration felonies by means of that same

zanja.

It’s been about six years, he told me; I remember that it was very hot that day in 2002; José was still rich in hopes of crossing the line and emulating the broccoli career of our mutual friend Lupe Vásquez.—It was three of us guys, he said. We had met in that place where, you know, where people wait to get jumped across. We went all the way to where the fence ends, and then there’s the canal,

329

and we tried it there, but Immigration was

hard,

so we went to the other side of Mexicali, the west side, and we saw the Border Patrol, but we saw more probability of making it, so we waited until it was dark and just started. We had heard stories of people drowning there, so we were kinda scared, but our willingness outgrew our fear. Then we waited until that Border Patrol Blazer started to move. It was our first time. We didn’t know we were supposed to take our clothes off and put them in plastic bags over our heads, so we came to America with wet clothes. It was winter season, so I got a job harvesting lettuce. Then I went back home. It had been a pretty good season, I remember. I saved about two or three thousand bucks.

How was the current? I asked him.

I don’t know if it was the fear, he said, but I didn’t find it really hard.

(We pause to insert into the record the testimony of Mr. Rose, who represents

a private corporation down there,

which is to say in Mexican Imperial; despite his professed animosity for Harry Chandler, he must have something to do with the Colorado River Land Company. It is the year 1925. He testifies to the Senate Committee on the Colorado River Basin:

It is nothing uncommon to pull out a dead horse

or dead cow along the canal, or even a dead man . . . It is an extremely long canal; it is imposible to keep them out. They swim out in the water; you see a whole family out there paddling around in the water; it is a common practice among the Mexican people.

But no worries! In answer to the query of Senator Dill, Mr. Rose explains that we filter the water, so that dead Mexicans cannot make us sick.)

José was just then getting ready to make his seventeenth crossing, maybe in a week or two when the harvest started. For now he’d keep sleeping on benches in Mexicali. I asked him where he would try it, and he said: Downtown Calexico, right where the Port of Entry is. It’s gonna be on my own, since I don’t have no money to pay a coyote . . .

Why not the canal? You did it that other time.

It’s too hard, he said, but I saw from the look in his face that if he thought he had to, he would still try it. One day I would come to Mexicali and ask for him, and he would not be here. Perhaps he would have made it into the United States, or perhaps he would drown in the All-American Canal, or it could be that thanks to heatstroke or a panicky driver trying to outrun the Border Patrol, the coroner would already have released him to the potters’ field in Holtville, or not improbably he would have given up, temporarily of course, squatting in Colonia Chorizo or returning back home to his two children and their mother in Jalisco. In any case, he’d become a mystery to me.

And in time he’d be as forgotten as a cigarette carton crushed into the dirt of Avenida México.

INFORMAL LIBERTIES

His identity might be forever a mystery, his fate unknown to all who loved him, his purpose unfulfilled, his family perhaps left to fall apart in poverty somewhere in Jalisco, but at least he would be free, a term which I use in the same sense as it was employed in the following Western Union telegram from the Deputy Customs Collector in Los Angeles to the Deputy Customs Collector in Calexico at 1:30 P.M. on a 1913 day: ADMIT CORPSE AND CASKET FREE ON INFORMAL ENTRY.

Chapter 176

THE LINE ITSELF (2003-2006)

Yet across the gulf of space, minds that are to our minds as ours are to those of the beasts that perish, intellects vast and cool and unsympathetic, regarded this earth with envious eyes, and slowly and surely drew their plans against us.

—H. G. Wells, 1898

O

ur primary mission is to prevent terrorism and terrorist weapons from entering our country,” El Centro Chief Border Patrol Agent Michael McClafferty said,

and in my mind’s eye I can see these agents of delineation, far less self-questioning or half-ashamed than on that first coolish night in 1999 when I rode along with Border Patrolman Dan Murray, who was now retired; his primary mission had been simply to keep unauthorized Mexicans out. It wasn’t that anybody who hated Border Patrol agents liked them better now, and they must have known that; but they themselves and the people whom they ostensibly protected from Southside now shared the fear, I repeat,

shared the fear;

they stood shoulder to shoulder together against their fear of Islamic murderers which seared Northside like sunshine itself; they could uniform themselves in haughty secrets now; they could be brisker and probably more brutal than they had been for many years; we submitted without a whisper. New powers and titles nourished them. There was a measure afoot to triple the wall where Imperial met the sea; leveling canyon and mesa, they’d be granted advance immunity from any legal or environmental questions. They were the sole adults in Northside; the rest of us were children or worse.

Once upon a time in 1915, the Treasury Department admonished the Collector of Customs:

The general belief that opium in powdered form, pearls, aigrettes or other merchandise must be illegally introduced into the United States is not sufficient warrant for subjecting every pedestrian crossing the border to such a search as was made in the case of Mr. Edmonston. You will be governed accordingly.

Oh, that was once upon a time, all right!

Near the beginning of this book I wrote about the first time they detained me, which was comparatively jolly. The second time I got to visit their little room, three years later, I suffered from optimism: We wouldn’t remain there long, since we hadn’t last time. At my ease, I took note of the love-word MEXICO scratched upon the metal bench on which we waited. I was with somebody else by then, a woman whose lineage and place of birth tied her, at least in the conviction of Northside’s new department called Homeland Security, to Arabs. I will never forget the way she went from irritated to furious to unbelieving to frightened in the course of that seven hours.