Imperial (182 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

W. F. Holt would have been glad to see this feedlot of dappled black-and-white cows whose many long bodies kept darkening into silhouettes.

Then the car turned left into Holtville, went left a block and left again on Sixth back out of town to the white crosses in their fresh-graded muck.

Do you remember what they wrote about Mr. Holt?

He works too hard to have time to sit around the corner store stove and whittle with the rest of the fellows, so when they get out to work they find the Holt fields are all plowed . . . Lots of people don’t like Holt; lots do.

That was all these illegal aliens in the cemetery had wanted, to work as hard as Holt did. Bad luck, in an unknown number of cases emblematized as Operation Gatekeeper, had caught them; and so here they were, home forever in Holtville.

Some of the crosses possessed wilted flowers, possibly from the Day of the Dead. A long cross made of carnation heads lay a dead body’s length in the muck before one cross with no name, not even

JOHN DOE

, simply

NO OLVIDADO

, and I touched a scattering of white bead-like things in the flowers; they were wax drip-pings.

When they get out to work they find the Holt fields are all plowed,

the sun now glaring right on top of the low trees at the edge of the potters’ field, the muck seeming to breathe, giving off a comforting breath of water-freshened earth, and the crosses, small and still and white, beginning almost to shine in the twilight.

And a big truck went by, and Holtville cooled. Birds began to sing. Night arrived; Imperial came alive.

Off the changing wind came a smell of manure.

IMPERIAL

The hatted heads like crops in the 1911 picnic “fiestas” of Holtville, so many ladies in white, the men often in dark suits, those squinting Western faces beneath the trees—where have they all gone? They’ve ridden away on that plank road of Edith Karpen’s memories, the road they used to oil from a cylindrical car pulled by half a dozen horses. They’ve gone to Yuma and beyond; they’re out of Imperial now.

Long trenches with poles across them supporting quarter after quarter of barbequed beef; farmers and neighbors together; that was Christmas in Holtville in 1909. Wilber Clark and his sister might have been present; perhaps Mr. Holt motored down from Redlands with his wife and daughters; the Edgar brothers had already opened a branch of their hardware store there; confident dreamers were growing grapes.

Manufacturing is hitting another level of evolution. You can’t produce things the way you used to.

So the grapes went away, and the farms dwindled in number and increased in acreage.

JOHN DOE’S PROMOTION

JOHN DOE

was born with a Mexican name.

He works too hard to have time to sit around the corner store stove and whittle with the rest of the fellows.

That was why he decided to go to Northside.

NEW TODAY!

Debt Collection Technician

Naturally

JOHN DOE

would never qualify for that exalted position.

NEW TODAY!

Agribusiness Warehouse / Delivery Person

Growing Western agribusiness [the newspaper never says which one] is looking for a Warehouse/Delivery person for our Holtville warehouse.

Once upon a time, in the years before Operation Gatekeeper,

JOHN DOE

could have gotten warehouse employment; even nowadays he might have aspired to such work had he known how to borrow someone’s social security number, obediently paying money into a system which would never return it to him in his old age

(they do work most Americans wouldn’t do);

a delivery job would have been more problematic, since he surely lacked a driver’s license.

NEW TODAY!

Field Labor

Growing Western agribusiness looking for a person who will not complain. No benefits; no job security.

That advertisement never appeared in the newspaper; advertisements were a waste of money in that business;

JOHN DOE

would wait regardless; I suspect he could not read the newspaper.

The sheriff’s department believes the deaths could outpace last year’s record of 95.

Yet as tragic as these events are, the patrolling policy, known as Operation Gatekeeper, is the correct one. I can’t help believing in people.

Some crosses had fallen; Terrie picked them up and set them right . . .

Chapter 202

CALEXICO (2003)

Among the outstanding attractions of Calexico are . . . 6.—Six miles of wastewater sewers and new sanitary outfalls.

—Imperial Valley Directory, 1930

A

t four-thirty in the morning the air smells sulphurous and sweet like Karachi, and a bird sings. A man walks briskly west, toward Donut Avenue, and a block away another man is also walking west. A truck goes down Fourth Avenue. The palm-tree shadows are crisp and still on the parking lots. A police car, a taxicab, a walking man in a work cap, a fingernail moon and a few stars, that’s Calexico at four-thirty.

But the deep blue sky is now going pink on the eastern end of Second Street, and men and women are standing at pay phones; people are emerging from the pallid blankness of the border station. Stores are lit but closed. An ancient brown man in a white Panama hat lopes along, carrying a plastic bag. At FALLAS PAREDES they’re pulling the racks of discount clothes onto the sidewalk because it’s already five, and across the street, under the Bank of America sign, half a dozen men sit on the yellow-lit sidewalk. Men stride rapidly toward Donut Avenue.

And in front of Donut Avenue there they are, at least two hundred of them, the lines and crowds of men in the parking lot, each huddle formed like a pearl around each truck or van. A big fat woman stands drinking coffee beside her man. Two men sit behind the dark window of a van, watching and perhaps choosing. In another van a man sits regally in the driver’s seat. Another man stands, leaning toward the open passenger door, swinging it idly. Men speak in brisk voices, smiling and even relaxing, with their plastic bags or backpacks slung over their shoulders.

Inside Donut Avenue, they are, of course, eating their doughnuts in paper bags, drinking their coffee, aggregating in threes and fours, most of them men although occasionally a woman will sit with several men. By the bank of video-game machines a man in white-salted boots kneels on the floor, reading a Jehovah’s Witness magazine. Most of the men’s clothes are clean. They do not speak loudly. Several of those whom I had taken to be chatting I now realize are dully rubbing their noses, gazing away from one another like people in elevators, waiting for the judgment.

A slender man in a cap which says FOXY stands in the doorway, one hand in his jacket pocket, the other on his coffee cup, and he strains his eyes, looking. A handsome young couple are flirting; a whitehaired, big-shouldered man in a checked shirt strides in as though he owns the world. A white van, crowded with the chosen, pulls away. Now it is five-thirty, with a few bloody sausage-shaped clouds at the eastern end of the pale blue sky. All the benches at the bus stop are full. A crowd of men listens rapturously to an older man tell a story in a sharp voice. One man whistles at another, who trots obediently toward him, while on a bus bench a third man watches them with narrowed eyes, working away with his toothpick. More of the battered vans head for the fields, honking. Across the street, on the sidewalk in front of Valley Independent Bank, a man begins to drone away with a leaf blower.

The man with the toothpick is very still now beside me. He crosses his legs, un-crosses them, and finally begins walking back to the border.

By seven, all that is over. The foremen have taken all the winners away! In the hotels, the smooth seagull-cries of women in orgasm are just beginning to pass through the walls. The sun is hot on the back of my neck. Lupe Vásquez is surely in the broccoli.

God, so that’s my life.

Then it is eight-o’-clock in Calexico when the wind smells like manure and the cashier inside the Rite Aid, which is still closed, has begun matching and inserting each drawer into each cash register. Rite Aid opens! Half a dozen people, most of them women, rush inside. And then Calexico is silent all day.

Meanwhile, the newspaper reports the coming of

a huge subdivision that could double Calexico’s population.

A young palm gently twitches in the hundred-degree night, and a cavalcade of automobiles—a good three of them—shines its way eastward on Third Avenue. In the windows of LA Selección, light clothes crowd against the glass like refugees peering through the portholes of a sinking ship, and crickets sing. A cockroach emerges from the manhole, scuttles briskly some two feet, takes fright and rushes home. How still it always is in those long hot archways! Is it my imagination or are they more brightly lit than before? There’s the old tower, white in the night, and the fence, through which the red brakelights of departing cars shine in Mexico.

Even there it seems quiet, due to the heat. But still, by ones and twos people speak to one another through the heavy mesh. An unshaven man glares piercingly into my eyes.

Chapter 203

EL CENTRO (2002)

Some lover of nature, seeking seclusion and health, has erected a cabin home, surrounded it with rustic comfort, and subsists upon the products of the rich responsive soil.

—Wallace W. Elliott, 1885

—A

nd change came; just as the urine of dehydrated people is turbid and dark,failing in transparency, so the evening sunlight, as if heated to exhaustion by and with itself, now lost the glaring whiteness which had characterized it since early morning, and it oozed down upon the pavement to stain it with gold; and suddenly

351

the lengthening angles of light alongside the railroad tracks and between the faded temples of agricultural success on Commercial Avenue became incredibly beautiful, the goldenness containing within itself an earthern rainbow of tans and browns; the next day I saw that same many-subsuming color in the hair of a woman who called herself Mexican-American and whose boyfriend even though he was thirty-seven could still make a baby if I knew what she meant; she’d had three children by three diferent men and they were all in foster care because the world kept kicking her when she was down; and she bore an ankh, the ancient vulva-based fertility symbol, tattooed on her upper arm; her parents were Christian and her brother was a Satanist, so she knew what was what (and while saying this she made it more than clear that she wanted me to do some business with her); and suddenly she became emblematic to me of Imperial’s troubled not to say polluted fertility, with her sun-colored hair and her silt-brown skin, her babies and her happylust to conceive more babies. When is conception a tragedy? When the pioneer generation took root in Imperial, it was “noble,” “heroic,” “romantic.” And now?

And change came.

A cliffhanger decision looms tonight for the most important water deal in California’s modern history . . .

That is what the newspaper said. How would the Imperial Irrigation District vote?

All the heavy weight is on the Imperial Valley,

opined a jeweler.

There were all these threats . . . that if we don’t do this deal, all these bad things could be done to us.

I think we all feel sorry for ’em.

Chapter 204

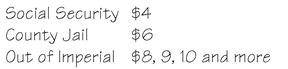

YELLOW CAB DISPATCHING PRICES, CITY OF IMPERIAL (2003)

Posted inside the taxi:

Chapter 205

LOS ANGELES (2002-2005)

The country was completely parched and desolate, but half-way up the hill we could see a green spot where a spring emerged from a mountain. It takes no more than this to create a settlement in Lower California.

—John Steinbeck, 1940

TÍPICO AMERICANO

The aggression of Palm Springs’s green lawns, casinos, gated communities, car dealerships and billboards, to say nothing of that literally grey eminence Los Angeles, with its myriads, its neediness and its greediness cushioned within cool smoggy mists, must surely conquer Imperial’s tranquil decrepitude, and indeed is already winning mile by mile.

It takes more “nerve” and more coin to invest in a corner lot than it once did, but the promise of returns is still good . . . A new water supply is coming; a mountain river has been annexed at great cost . . .

A booster wrote those words about Los Angeles in 1911. Nearly a century later their veracity has been refreshed, thanks to the water transfer from Imperial County. The promise of returns may indeed be better than ever, at least for the super-rich. Within ten or twenty years, won’t Indio be another suburb of Los Angeles? The

Imperial Valley Press

proudly announces the forthcoming appearance of this hotel chain and that fast food franchise in El Centro. When the new border checkpoint opened on the east side of Mexicali, which is to say considerably eastward of Mexicali’s puny counterpart Calexico, people told me that another of Northside’s industrial parks was going to sprawl and slither there; in some adjoining future year, Calexico will reach at least that far, manifesting what those of us to whom only human concretions are important have named “southern California,” meaning lawns and telephone poles, palm trees getting moved in on by baseball fields, the desert turning the color of money: green-green, greeny-green!