Imperial (185 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

Next I had to account for the fact that some of Imperial lies south of the international border. How much, exactly? From the bicultural standpoint which we have been considering in the previous paragraph, Imperial might extend indefinitely down the Baja Peninsula, where petroglyphs are matched by Anglo-owned resorts. (One Mexican historian claims that the border region

extends out at least sixty miles in both directions. By this calculation, the border region exceeds in square miles the territory of nations such as Spain and France.

) That may be true for the border as a whole, which continues alongside Arizona, New Mexico and Texas. But one of Imperial’s most notable characteristics is

slowness,

in evidence of which I advance the tortoiselike promenades of Mexicali’s citizens on cool afternoons, the almost-empty black streets, the angle-parked cars which remain in place for days, the stands of fruit awaiting their once-per-hour buyers. It made intuitive sense, given the un-Imperial, hustling, honkytonk character of Tijuana, and the equally foreign busyness and American-ness of the tourist resorts in Baja California below it—and also given the fact that on a pretty map I have, entitled “Phytogeographic Regions of Baja California,” this northwest corner of the peninsula has been colored emerald green, in deference to coastal scrub—to rein back Imperial’s frontier here to a few more border pulsations which will appear quite pretty in symmetry with the ones we’ve now agreed to establish to the Northside, while permitting the eastern portion of Imperial to extend much farther south—say, to the resort town of San Felipe, which was historically an entry point for illegal Chinese immigration into Imperial. You’ll be ecstatic to hear that “Phytogeographic Regions of Baja California” endorses my stand, for the tan zone called “San Felipe Desert,” driest of all the peninsula’s many arid places, runs neatly down the eastern side, outpacing its emerald green opposite, which quits at El Rosario.

And why should we stop at San Felipe? The tan zone keeps going, all the way past Bahía de los Angeles to the jade-colored coniferous zone. Not knowing the answer in advance,

359

I feel obliged to take you on a trip:>

Mexicali, if we ignore the zone consecrated to

GARY

WELLS WORLD CHAMPION MOTORCYCLIST, fades with graceful irregularity into Imperial desert, its house-cubes and

WORLD CHAMPION MOTORCYCLIST, fades with graceful irregularity into Imperial desert, its house-cubes and

carnicerías,

which are sometimes broken-windowed, colored like the illustrations in children’s books, then dusted over again; and gradually there are fewer cubes and there is more dust. Between two lanes of traffic, a man is selling plastic bags of strawberries. Smoke transects the concrete cube of

VIDEO LUCY’S.

At the side of the freeway, a cowboy is posting, gathering in his dark cows. Here Imperial’s fences begin to incarnate themselves in posts of saguaro cacti. A feedlot with its wall of bales could have been stolen from Northside. Next comes a palm orchard, the trees smaller and more densely planted than around the Salton Sea. Following Cerro Prieto at Kilometer 22, there comes the tan country, whose rivelled sand could have lain in any of the washes between Bombay Beach and Niland if it hadn’t borne such a wealth of grey-green brush. Two roadside crosses with immaculate plastic flowers, a beehive kiln in the dirt, a roadside restaurant built to resemble a six-pack of Corona beer, bottletops and all, any one of these might mark the end of Mexicali’s sprawl; certainly by Kilometer 50’s mounds of gravel and sand we’re in the midst of what the woman I was with called “that vast feeling,” that dream of emptiness as wholeness. For awhile the valley floor grows carpeted with olive-hued shrubs (mainly creosote bush). In early spring there are many yellow blossoms here. Farther south, around Kilometer 70, the vegetation begins to thin out again, the soil to blanch and crack. By Kilometer 75 the earth is naked, reddish, nearly vegetationless, a plain marked only by occasional ruined tires or the rarer salt-rimmed pool, around one of which I see men fishing to the accompaniment of a guitar. Right after the military checkpoint (green-clad soldiers jittering their machine guns at each approaching car), creamy sand dunes like better-vegetated cousins to those in Algodones mark another Imperial trick, and before I know it, the vegetation has grown up into rich green trees. This would seem to be the boundary of the Desert Lower Sonoran Life Zone. Cones of reddish lava bedeck the world. According to some sources, the Mexicali Valley, which of course is the Mexican half of the Imperial Valley, ends right here. Why not end Imperial itself here in that case? Well, the main reason is that I

want

to go farther. But here’s a rationalization, too: Highway 5 is about to go back down again, back into the Desert Lower Sonoran Life Zone. Kilometer 99 offers Imperial’s trademark extreme flatness on the left, jagged volcanoes on the right. From a distance, the salt flats around the cinder cones far ahead resemble shimmering water. And so the highway descends from the reddish lava-hills into this other vast plain striped with salt more or less as Jupiter is striped with gases: softly, colorfully and luminously. Nodding to the Sierra las Pintas at around Kilometer 120, the road passes a broken concrete encomium to a disco which died or never happened; Imperial is loved not only for its corrals of agave sticks but also for its high failure rate. Off to the left, the white-rimmed Colorado follows and borders Imperial, but at some point, it’s turned into the widening electric-blue line of the Gulf of California, which John Steinbeck described as

a long, narrow, highly dangerous body of water.

360

Thus at around Kilometer 186, we’ve reached San Felipe, a decent place to eat steamed clams and fish tacos while vendors walk slowly past, selling postcards and fourth-rate jewelry. The sea-fog makes it feel a little like San Diego. A round white sign says: SAN DIEGO BEACH OK. Isn’t this far enough south? The San Felipe Desert and the Desert Lower Sonoran Life Zone stretch on, and we’re only halfway to Puerto Refugio, where in 1940 the

Sea of Cortez

achieved her farthest north and swung round to sail down the east coast of the Gulf; but San Felipe seems pretty deep in Mexico just the same; we’ve left the Mexicali Valley behind. By fiat, Imperial ends here.

361

This version of the second map will remain unpublished. I had orginally envisioned

Imperial

as containing detailed chapters about all the native American groups within this area of study. My failure to do so rendered the old version of the map arcane to the general reader. This recapitulation of what it contained was prompted not only by the spirit of querulous attachment but also by an abiding belief that the boundaries of the entity I call Imperial do “mean something” from a material point of view.

The current version of the second map simply indicates Imperial’s territory, eschewing comment.

PERSONS AND PLACES IN IMPERIAL

The third map (page xxvi) locates a few people and places mentioned in the text.

RIVERS AND CANALS IN IMPERIAL

The next map (page xxvii) roughly delineates some of Imperial’s major waterways. My two base maps were from 1906 (to show where the New River / Río Nuevo used to flow from) and 1962, when the All-American Canal and Wellton-Mohawk were both in place. Canals on the Mexican side are grossly underrepresented because what depictions I found were inconsistent.

MY NEW RIVER CRUISES

The last map (page 84) is a closeup of the American portion of the New River as I met it in 2001.

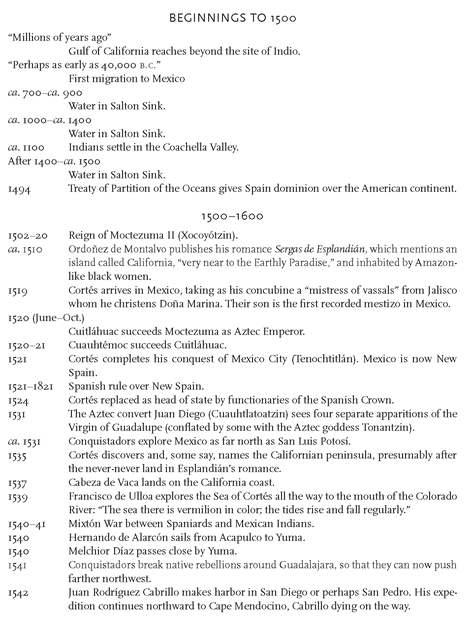

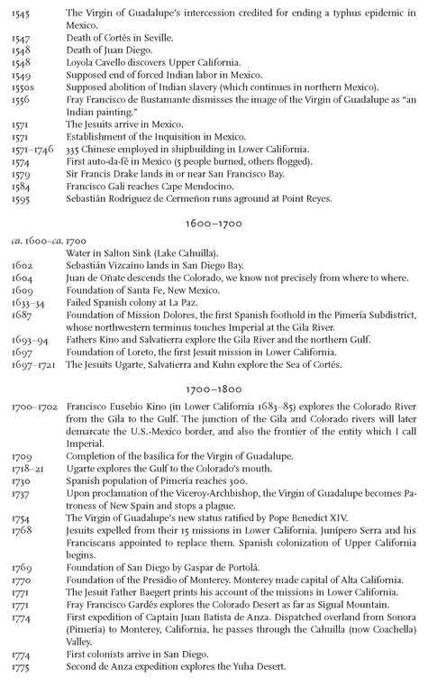

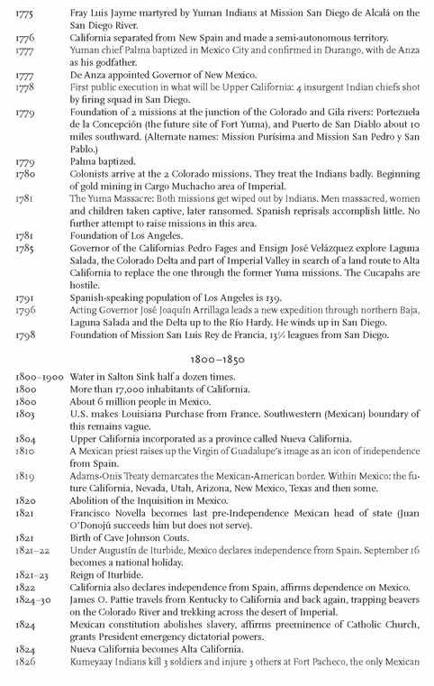

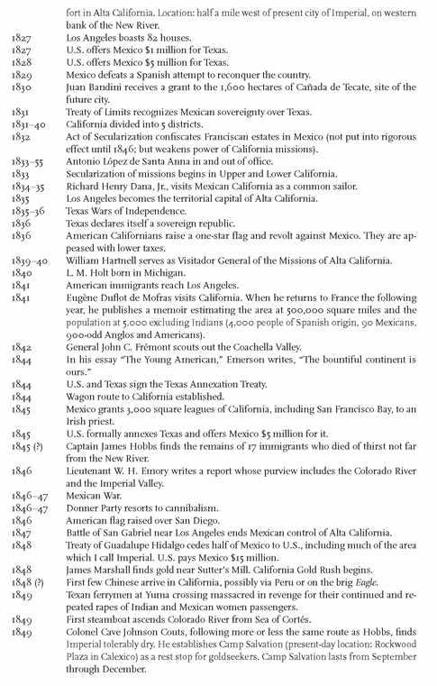

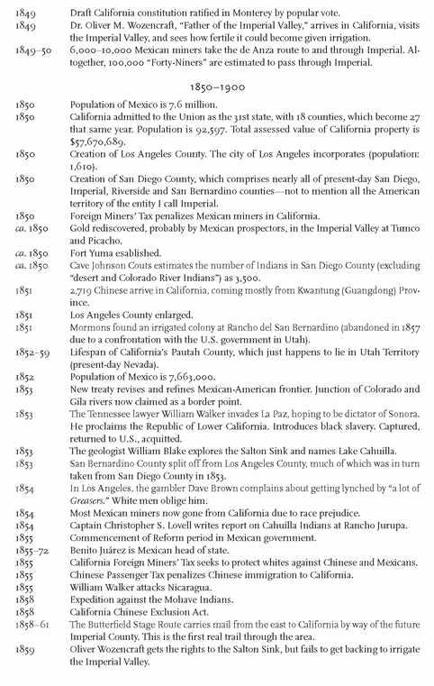

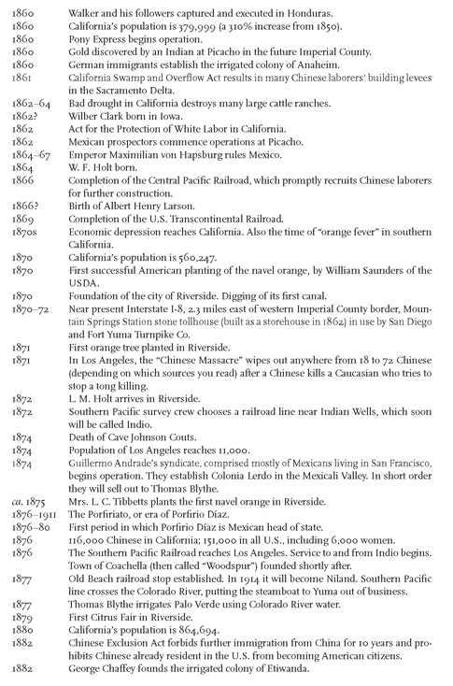

A CHRONOLOGY OF IMPERIAL