Imperial (69 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

Who are the new refugees to us? We decline to think of them any longer as noble Californios; a 1912 history of Riverside County falls more on the mark when it describes them as

the miserable half-breed race

which steals white people’s cattle and horses; at least they’re not Chinese; our Exclusion Acts will keep the Celestials in Southside, picking cotton for the Colorado River Land Company.—In 1919, only five percent of the arrestees in Imperial County will be Americans,

the rest being Mexicans, Hindus and other foreigners.

Now let’s put those foreigners to work!—I wonder what the result might be?—Irrigation democracy at its best, no doubt.

Santiago Gonzales from Las Barrancas sets off for Northside. He gets a job in the California gold mines. When he returns, he’s so well off that while preparing to throw a party he washes down the patio with expensive tequila.

Well, from then on many of the men from Las Barrancas went.

Near the end of a long career studying California’s underclasses and water politics, with frequent reference to American Imperial, Paul S. Taylor compiles a list of numbered points in his “Imperial Valley, Notes, Drafts,” dated 1979. Here are two of them:

13. The applicability of acreage limitation to Imperial Valley . . . is the essence of national policy on how land should be used. Without the law, Imperial Valley is a polarized society. Virtually 9 out of every 10 persons engaged in its agriculture are part of a “lower class” “mass of laborers.”

(Who might they be?

Well, from then on many of the men from Las Barrancas went.

)

14. . . . These people, overwhelmingly of Mexican origin, are virtually landless. The purpose of applying acreage limitation law as defined by the U.S. Supreme Court, is “to benefit people, not land.”

Well, they did it to themselves; nobody forced them to come. And until 1913 there’s not a single labor union in Imperial County.

A PAGEANT FOR SCHOOL TEACHERS

And so Northside watches Southside, apprehensive of trouble but hoping still to get while the getting’s good. Comforting herself with her superiority

(the entire equipment of the United States regulars at Calexico is considered far in advance of that of the Mexicans across the border),

American Imperial enjoys Mexican Imperial as exotic theater—trusting, I should suppose, that the performance will stay literally within bounds.

We see ladies in long dresses and big hats, adorned by purses, all smiling or half-smiling upon the dirt. The caption reads:

TWENTY-FIVE IMPERIAL VALLEY SCHOOL TEACHERS VIEWING THE ACTIONS OF THE REVOLUTIONISTS IN MEXICALI, BC, FEBRUARY 11, 1911.

The border post will be razed by arson that night.

In 1914, the following page-one news arrives from Southside:

Embargo Is Established On Huerta’s Orders

. . .

No mention is made of the rebels’ claim yesterday that Mazatlan had fallen . . .

On the same page, we read Northside’s counter-preparation:

Platoon of Machine Guns Arrives; Militia to Depart

. . .

With the arrival of a platoon of machine guns of the First cavalry, Calexico’s military garrison was greatly strengthened.

Seventh California Infantry has also been dispatched to Calexico. And finally, again on page one, we find the most important news of all:

Cotton Industry Reaching Giant Proportions Here.

We have two weeks yet before the opening of the cantaloupe season; the Holton Power Company is supplying us with mountains of ice . . .

THE PAGEANT THREATENS THE AUDIENCE

But there come moments when ice cannot keep the Imperial Valley cool.

At the end of 1910, which is to say of the grand year that Westmorland incorporates, Huey Stanley leads the Wobblies across the line, establishing socialism in Mexicali’s wide white streets! The following February, his army defeats the troops of Kelso Vega, Governor of Baja California. But in April he falls in battle, leaving Mexicali as he found it, namely, sandy and mostly bereft of buildings, the few in existence being scaffolded and low, while blurred people in antique dress walk past a now antique car.

Then come those American revolutionists of 1911, who incarnate William Walker all over again. But after all, who

isn’t

trying to put his face on the Revolution? In the Imperial County Historical Society Pioneers Museum there is a Hetzel photograph captioned

Horses stolen by insurgents, Mexicali, Mexicali, Jan. 29, 1911.

I see a blur; I see four men and four horses. I see

Lieutenant Berthold inspecting insurgent troops, Mexicali, 1911.

They are a blurry line of hatless men standing on a grey blur; possibly they are the same people who belong to the

detachment of Revolutionists patrolling the railroad in Mexicali, 1911.

The events of 1911 remain not only convoluted almost beyond belief, but obscure in their details. On 28 January, Ricardo Flores Magón, revolutionary anarchosocialist and therefore natural enemy of Porfirio Díaz, sends his Magonistas to Mexicali. Or do they go by themselves? What can be the true role of this unbending dreamer, who passes so much of his life in various Mexican and American jails? Perhaps in his honor, the Magonistas kill the jailer in Mexicali and release all prisoners; the government runs; two bridges get destroyed. In answer, certain altruistic Northsiders (call them friends of the Colorado River Land Company, some of whose stockholders have now utterly lost heart and long to get rid of their Southside properties) form a private army. On 7 March, thirty thousand American soldiers stand along the border, ready to come in. Who stationed them there? Did Harry Chandler send somebody a telegram? On 12 March, the Wobblies take Tecate. Meanwhile the mercenary Caryl Ap Rhys Pryce attacks Tijuana, which falls on the ninth of May. Upholding the highest principles of international liberation, Pryce’s men pillage the city. They charge tourists a quarter per visit. Then they get ready to seize Ensenada. It is actually now that Madero becomes President and calls for the factionalists to make peace. Pryce refuses, embezzles funds and leaves. In Northside, Magón likewise keeps the faith. Now Dick Ferris from Los Angeles, who once tried to blackmail Díaz into selling the entire Baja Peninsula, tries to pull a William Walker in Tijuana. Magón’s replacement general, Jack Mosby, accordingly denounces Ferris; the Federales retake Tijuana; Mosby flees to Northside but gets arrested, as does Magón, who, sentenced to twenty-three months, dies in jail after years and years. South of Tijuana there’s an Ejido Flores Magón; that’s all that’s left of him.

Just to thicken the plot, other altruistic Northsiders, who evidently bear less connection to the Colorado River Land Company than to the dreams of some new William Walker—or who knows? maybe they’re even Magonistas—send a night letter to the Governor of California:

We, the people of Los Angeles, in mass meeting assembled have adopted a resolution in sympathy with the Mexican Insurrectionists and have asked our government at Washington to declare the revolutionists to be belligerents, so that they may receive all the rights of soldiers under international law.

Perhaps on their account, or on account of people like them, in 1914 the

Imperial Valley Press

complains of a certain hardening of the line:

It is not possible any longer to make a dash across the Mexican border into Mexicali, as the Mexican customs officials have inaugurated a policy of minutely searching all who enter the city.

In the same breath, one speaks of Apricot Day.

Fruit and Vegetable Day Reflects Wealth of Valley.

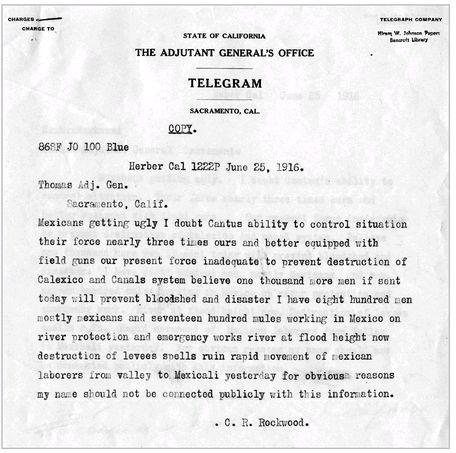

In that same year we hear and pass on rumors that Mexicans might cut the part of the American Irrigation Canal which lies on their side. We form home guard volunteers. In 1916, the Adjutant General of California receives a panicked communication from none other than Charles Rockwood, whose imprudent engineering gave us the Salton Sea. The telegram deserves to be shown in full, since every word of it is classic, right down to the determined refusal to capitalize the word “Mexican”:

116

Calexico mysteriously survives.

And it goes on and on like this in the border cities of Southside, while Northside watches from as far away, perhaps, as the Tinken Ranch in Calexico with its twin silos one of which reads PERFECTION. Surely there must be other times when the pageant threatens this audience. Did you know that in 1919, one out of every five American laborers went on strike? That was the year of the Red Summer Race Riots. The Ministry of Capital doesn’t care for that. Moreover, some of the shouts we hear from the other side of the ditch sound pretty damned Red.

HOLDING THE LINE

And so, come 1925, when Phil Swing demands an All-American Canal, he deplores for the edification of the appropriate Senate Committee

the uneconomic method of that great irrigation district,

namely Imperial County’s,

which has to spend between two and three million dollars annually in operation and trying to do business under two flags, and one of those flags a nation which has not maintained for some eighteen years any very stable form of government, whose people have not in recent decades shown any particular friendship for our people.

(I wonder why they don’t like us? In 1920 an American crosses the line at Calexico, asks to be taken to Cantú, the current Governor of Baja California Norte, and offers to smuggle weapons and ammunition to the good people of Southside. What credentials might he possess? Well, he has already transacted this same business with

Carrancistas and revolutionists in Mexico.

Cantú questions him in detail, then turns him over to the Americans.—In 1926 the

Imperial Valley Press

warns us of a certain M. Y. Mejía or Mejís,

believed to be the leader of bands which were partially organized in this section for an intended attack on Mexicali at the time of General Estrada’s ill-fated expedition . . . Mejis is known to have been in Seeley Sunday.

)

Phil Swing calls for more ruthless and complete delineation.

The canal in Mexico is for a great many miles above ground,

he warns,

and open to attack and destruction—when I was there as a county officer we were in great fear during the fight between the contending factions, when one faction held the capital, Mexicali, another army of another faction was camped upon the Colorado River and planning to . . . with a few sticks of dynamite cut off the water supply of the city of Mexicali.

Worse yet (for who cares about Mexicali?), they could have forced

us

out, all sixty thousand of us; because in the Imperial Valley we have stockpiled no more than three or four days’ worth of water.

Chapter 69

THE NEXT STEP (

ca.

1925)

B

y the mid-twenties,

writes Paul S. Taylor,

they succeeded in obtaining legislation assigning quotas to immigration from nations of Europe, Asia and Africa . . . The next step . . . was to try to close the western doors also, and especially to limit the recently emerging flow of immigrants from Mexico.

Chapter 70

EL CENTRO (1925)

The husbandman here does not think of his fields being moistened by the falling rain. He digs ditches around them, in which water is conveyed from a stream . . . whenever moisture is required.

—James O. Pattie, 1830

R

oth and Marshall’s Feed Store, El Centro: Two men, one in a hat, stand duty behind the long counter one pan of whose scales rests upon a box of bag balm; from the ceiling hangs an immense proclamation of American realism:

OUR TERMS ARE CASH. NO NEW ACCOUNTS OPENED.

I have never been cheated out of a dollar in my life.

How could I be? For in 1925, the El Centro Chamber of Commerce announces what we all knew would happen: Imperial County, California, is

THE THIRD RICHEST GROWING COUNTY IN THE UNITED STATES AND THE RICHEST PRODUCING AREA IN THE WORLD

.

A hundred and sixty thousand acres of alfalfa now, ha! And thirty-four hundred acres of tomatoes, twenty-three thousand acres of lettuce, forty-six thousand acres of barley, seven point nine million pounds of butter, all in 1925; don’t you dare think I couldn’t go on. And El Centro must therefore be—just think of it!—the county seat of the richest-producing area in the world! No wonder that here we find the chosen residence of Cary K. Cooper, Assistant Secretary and Manager of the Pioneer Title Insurance Company.

Mr. Cooper richly deserves whatever success has come to him, for he now holds a prominent place in the business world.

He sold out at a fancy price. Not far from Mr. Cooper (for one can easily stroll from one end to the other of this young city), at 513 Brighton Avenue, dwells Imperial County’s own Herodotus, Otis P. Tout. About him and the ones he chronicled it could well be said:

He had enormous and poetic admiration, though very little understanding, of all mechanical devices. These were his symbols of truth and beauty.

The above words were published in 1922, in Sinclair Lewis’s now classic

Babbitt,

whose vulgar, greedy, jingoistic protagonist is oddly sympathetic in his feeble and indeed mostly unconscious rebellion against the world of multiply replicated emptiness which he inhabits and busily sustains.

I have never been cheated out of a dollar in my life.

Isn’t that the most Babbittish thing you ever heard?

He now holds a prominent place in the business world.

Is that so bad? Not necessarily; nor is Babbitt, whose home is

a high-colored, banging, exciting region

of new factories and old; the author means it to be any small American city, so could it be El Centro, too?

OUR TERMS ARE CASH.

You can’t hate them properly,

says one of Lewis’s characters,

and yet their standardized minds are the enemy.