In the Land of INVENTED LANGUAGES (18 page)

Read In the Land of INVENTED LANGUAGES Online

Authors: Arika Okrent

However, in most ways, the advance of English was very bad for the international language movement. The more common reaction was to stick up not for an invented neutral language but for your own home language, as France did in meetings of the League of Nations. Another alternative was to just accept English as the new lingua franca, as Sweden and Norway did in those same meetings. (Denmark wanted Ido.)

By the beginning of the 1920s, English had accumulated a heap of advantages—economic power, political power, large numbers of speakers—but it was not the only potential world language in town. French, Portuguese, Russian, and other colonial languages also enjoyed such advantages (though none on as grand a scale). However, by the end of the 1920s, English had added to its arsenal even more compelling advantages: jazz, radio, Hollywood. It became the language of a

new, media-driven popular culture. It was the lingua franca not just of elite pursuits—diplomacy, business, science, belles lettres—but of good ol' entertainment. It swaggered around with a gum-cracking friendly confidence, shaking hands and winning people over.

It also seemed to already possess many of the qualities that the language inventors were after. When Count Coudenhove-Kalergi, son of an Austro-Hungarian father and a Japanese mother, founded the Paneuropean Union in 1923, he proposed that English be the language of its administration, claiming that the “ease with which the English language may be learned, and its intermediate position between the Germanic and the Romance language groups, predestine it to the position of a natural Esperanto.”

The 1920s was the last decade of vigor in the second era of language invention. Though a few international language projects continued to crop up every year (as they still do today), even the language inventors were turning toward English. These inventors accepted English as an international language, but thought it could be made into a

better

international language by getting rid of some of its messy inconsistencies.

Some focused exclusively on spelling reform, as the Swede Robert Zachrisson did in his

Anglic

(1930):

Forskor and sevn yeerz agoe our faadherz braut forth on this kontinent a nue naeshon, konseevd in liberty, and dedicated to the propozishon that aul men ar kreaeted eequal.

Others sought to regularize the grammatical irregularities, as Ruby Olive Foulk did in her

Amxrikai Spek

(1937):

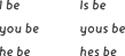

Pronouns and verbs:

Plurals:

man, mans

Comparatives:

good, gooder, goodest

Other regularizations:

Frenchman, Americaman, Italiman, Mexicoman

historiman, scienceman, artman, musicman

The best-known project of this kind was C. K. Ogden's

Basic English

, first published in 1930. Ogden was a Cambridge-educated editor, writer, translator, and mischief maker. As a student, he opposed compulsory attendance at chapel and, with a few of his like-minded friends, founded a group called the Heretics Society, where he honed his skills in questioning authority and challenging dogma. He supported progressive social causes like women's rights and birth control, and generally enjoyed being on the wrong side of stuffy propriety. At his own request, his entry in

Who's Who

says that he spent 1946–48 “bedeviled by officials.”

Basic English was his proposal for an international language based on a reduction of English to 850 words. Though he believed in spelling reform, he was practical enough to see how unlikely it was to be accepted (he called it “a problem waiting for a Dictator”), and instead tried as much as possible to build his Basic vocabulary around words that presented “no special difficulty.” He claimed that of the 850 words he had chosen, “less

than a hundred involve wanton violations of orthographical decency.” He also objected to irregular plurals and past-tense forms, blaming their persistent existence on a dastardly cabal of “printers, lexicographers, and schoolmasters.” However, realizing that an English that looked like English was more likely to succeed, he left the grammar alone.

Instead, he simplified the language by doing away with words like “disembark,” “tolerate,” and “remove” and replacing them with “get off a ship,” “put up with,” and “take away.” In this way, he eliminated almost all verbs—including “to eat” (“have a meal”) and “to want” (“have a desire”)—from his list of 850, leaving them to be expressed with what he called “operators” like “get,” “put,” “take,” “come,” “go,” “have,” and “give.” Ogden believed that such a recasting not only made English easier to learn and understand but also had the potential to cure our minds of some bad habits. He believed that much of the world's troubles could be traced to the negative effects of what he called “Word Magic,” the illusion that a thing exists “out there,” just because we have a word for it. When we are under the spell of Word Magic, we fail to see that “sin” is a moral fiction, “ideas” are “psychological fictions,” “rights” are “legal fictions,” and “cause” is “a physical fiction.” (He also feels compelled to pick on “swing” by pointing out that it is a “saxophonic fiction.”) Word Magic makes us lazy; we don't question the assumptions that are hidden in words, and so we allow ourselves to be manipulated by “press, politics, and pulpit.” Ogden thought Basic English could work as an antidote to Word Magic by forcing people to express themselves in simple terms, thus forcing them to really think about what they are saying.

Winston Churchill, himself a tireless advocate of plain language, was a fan of Basic English and made efforts to promote it. He thought it could help create a different kind of empire, one based

not on “taking away other people's provinces or land or grinding them down in exploitation” but on a shared language. He encouraged the BBC to take it to the airwaves and teach it far and wide.

He also appealed to President Roosevelt to join the cause of Basic English. Roosevelt promised to look into the matter, but he couldn't resist teasing that Churchill's inspiring speech about offering his “blood, toil, tears, and sweat” to his country may have been less effective if he “had been able to offer the British people only blood, work, eye water and face water, which I understand is the best that Basic English can do with five famous words.”

For all they did to argue for its virtues, neither Churchill nor Ogden actually used Basic English in their own writings. They rather took luxurious advantage of English vocabulary. But Ogden didn't really intend for Basic English to replace full English. It was to serve as a second, auxiliary language, a utilitarian lingua franca. He advertised two other benefits. For foreigners, it would serve as an easy entrée into fuller English. For English speakers, it would serve as “an apparatus for the development of clarity of thought and expression.”

I'm not so sure Basic English fit the bill on either point. Although sometimes the Basic English version is clearer (“First, God made the heaven and the earth.” I like that. It's snappy), at other times it seems to strangle itself on its own restrictions:

Seven and eighty years have gone by from the day when our fathers gave to this land a new nation—a nation which came to birth in the thought that all men are free, a nation given up to the idea that all men are equal.

“Came to birth in the thought that all men are free”? How does that clarify things? And if you don't speak English, how are you

supposed to know that “given up to” means “dedicated to”? Just because you are familiar with the “operator” words that Ogden expected to bear the brunt of so much meaning, you don't necessarily have any idea what they mean when put together. It is precisely those words, and the huge number of idioms they participate in, that make English such a headache for the non-native speaker. You haven't really solved much by replacing “happen” with “come about,” “tease” with “make sport,” or “intend” with “have a mind to.”

In 1943, Churchill touted Basic English in a speech at Harvard, and soon the reporters were at Ogden's doorstep. He received them wearing a mask and, over the course of the interview, exited and entered the room through different doors, each time wearing a different mask. This behavior was a symptom of his generally irreverent attitude and what friends called his “impish humor.” He wore masks on other occasions, explaining that when the speaker wears a mask, the listener is forced to pay attention to the content of the speech. Whatever the content of his speech that day, he did nothing to dispel the impression that Basic English was kind of a kooky idea. When Churchill left office in 1945, officials at the BBC suggested that Basic English be left “on a high shelf in a dark corner.”

Ogden's plan wasn't without merit. The promotion of plain language is a fine idea and I'm all for it. A simplified form of English is clearly a good thing for someone trying to learn the language. In 1959, two years after Ogden's death, the Voice of America began broadcasting news stories in something they called Special English, and these programs are still popular today in non-English-speaking countries all over the world. Special English is simplified, but not according to any particular theory or rules. It doesn't have anything against verbs, and while it has a core vocabulary

of fifteen hundred words, other terms are introduced when they are needed, along with brief explanations. The few rules it does claim—no passive voice, one idea per sentence—are violated when they interfere with sensible judgment. It is what Basic English probably would have become if Ogden wasn't so hung up on grand philosophical justifications for his system. Or with having it be a “system” rather than a loose set of guidelines.

Basic English also might have had a better chance if Ogden had been a little less eccentric. But it almost didn't matter what his personality was like, for by the time he came along, the whole endeavor of inventing or even manipulating a language had been so thoroughly tainted with the eau de quackery that even the most sober, sensible language inventor had little hope of being taken seriously.

Language schemes had always been viewed a little skeptically. John Locke, a contemporary of Wilkins's, said he didn't think that anyone could “pretend to attempt the perfect reforming the languages of the world, no not so much as of his own country, without rendering himself ridiculous.” But in the seventeenth century, highly prestigious people were working on the development of philosophical languages, and their work was circulated and discussed among the biggest names of the day.

And although at the beginning of the era of international languages, plenty of jokes were made at the expense of Volapük and Esperanto and other languages that came to public attention, they did get attention, and sometimes from quite esteemed sources. Respected institutions like the American Philosophical Association and the American Association for the Advancement of Science got involved in the international language question, and major papers reported on the different projects as they came out. Esperanto got a lot of press. In 1910, when the sixth universal Esperanto congress

was held in Washington, D.C., the Washington

Evening Star

carried the headline “Zamenhof Alvenas” (Zamenhof Arrives), and the

Washington Post

ran daily stories on the program of events.

Public recognition of invented languages manifested itself in other ways, too. A Scottish company produced an Esperanto cigarette (“The international smoke”), and Cadbury manufactured an Esperanto chocolate. When the universal congress was held in Barcelona, the king of Spain sent a horse-drawn carriage to pick Zamenhof up on his arrival. Later, as Zamenhof traveled south to Valencia, groups of people came out to greet his train at different stations, waving and cheering him on.

As time went on and the crackpot element of Esperanto society became more pronounced, people concerned about their public image became less willing to be associated with it. And as the number of invented languages increased to the point where the language inventors were (in the words of one newspaper editorial) fixing to “out-Babel Babel,” the newspapers and the scientific academies stopped paying attention.

Hundreds of language projects were published at the beginning of the twentieth century, and many of them were second or third attempts by people who weren't quite satisfied with their own original “optimal” solutions. Language inventors are, after all, motivated by the urge to reform and improve, and many of them, once they got going, found it hard to stop. They grew dissatisfied with their own projects and continued to tinker and adjust, publishing revised versions of their languages. Ernst Beermann, not satisfied with his Novilatiin (1895), later created Novilatin (1907). Woldemar Rosenberger (onetime director of the Volapük Academy) created Idiom Neutral (1902), followed by Idiom Neutral Reformed (1907), followed by Reform-Neutral (1912). Some of the most prolific producers were former Volapükists, such as Julius Lott, who

gave us Verkehrssprache (1888), Compromiss-Sprache (1889), Lingua Internazional (1890), Mundolingue (1890), and Lingue International (1899); or Esperantists, such as René de Saussure (brother of Ferdinand, the father of modern linguistics), who gave us Antido I (1907), Antido II (1910), Lingvo Kosmopolita (1912), Esperantida (1919), Nov-Esperanto (1925), Mondialo (1929), Universal-Esperanto (1935), and Esperanto II (1937).