In the Land of INVENTED LANGUAGES (20 page)

Read In the Land of INVENTED LANGUAGES Online

Authors: Arika Okrent

In 2007, I met with Ann Running, a woman in her thirties with severe cerebral palsy, at a group home for the disabled in Toronto. This is how we communicated: I moved my hand over a laminated chart of about eight hundred words that was attached to a tray on her wheelchair. The words were arranged both

thematically (food words, sports words, color words, and so on) and by grammatical function (pronouns in one section, prepositions in another). At each section I stopped and checked to see whether she rolled her eyes upward. If she didn't, I moved to the next section. If she did, I pointed to the top of the first column of words in that section and checked for the eye signal, pointing to each column in turn until she indicated I had reached the correct one. When I had the right column, I started down the column, pointing to each word in turn until she signaled. Then we started the process again, until Ann had said all the words she wanted to say.

It was an incredibly slow and frustrating way to have a conversation. Often, I missed her eye signal—a random jerk of her body could make me think she had signaled when she hadn't—and I had to back up and check that I had the right section or column. Also, she refused to let me finish a sentence for her, even when it was completely clear where she was headed. And Ann didn't take any shortcuts. Her sentences were complete and grammatically correct—when she wanted to say “told,” she didn't just lead me to “tell,” but to “tell”

and

to an entry indicating past tense. When she wanted a name or a word that wasn't on her chart, she directed me to a section that had the alphabet arranged on a grid, and she spelled the whole thing out, letter by letter, even when I guessed the word correctly. She made no concessions to convenience.

To my convenience, that is. Her whole life was inconvenience, and she was accustomed to it. She depended on others to feed her, to dress her, to put her to bed at night and get her out of bed in the morning. She had no control over anything having to do with her body. But she did have control over her mind, and in

her use of language she could prove it. She was not going to leave it up to me, and my convenience, to guess at a good enough approximation of her intentions. She had the ability, as difficult and time-consuming as it was, to say what she wanted to say, in exactly the way she wanted to say it, an ability that most of us take for granted. Ann had known what it was like not to have that ability, and she was never going to take it for granted.

I had come to Toronto to find out more about Blissymbolics, a pictorial symbol language invented by Charles Bliss in the 1940s. I had found a copy of his 1949 book about his system in a used bookstore in Washington, D.C. It was full of rambling Utopian philosophy and naive scientific theories (complete with references to

Reader's

articles). I was delighted to add it to my collection of nutty universal language schemes that I considered myself to be single-handedly rescuing from obscurity. Upon further investigation, however, I found out that Blissymbolics was not as obscure as I thought it was. There was a school in Canada for children with cerebral palsy that was actually using it for communication. But what, exactly, were they doing with it? How could a language as crazy as this one be useful for anything?

Ann was a graduate of the program at the Ontario Crippled Children's Centre (now called Bloorview Kids Rehab) that had started using Blissymbolics in the 1970s. But like all the other program graduates I visited on that trip, she now interacted through English text. All of the students I met with talked about the way Blissymbols had changed their lives. Ann said Bliss had “opened a door to my mind.” But none of them used the language anymore. Why, I wondered, hadn't they just started with English, a language they could hear and understand, rather than

spend their time learning this bizarre symbol language? I thought about Stephen Hawking, who communicates in a manner similar to Ann's (his computer pages through the word choices for him, and he clicks a device with his hand when it arrives at the word he wants). He never had anything to do with Blissymbols and gets along just fine.

I mentioned this, delicately, to Shirley McNaughton, the teacher who had started the Blissymbol program. “Oh,” she said, “but Stephen Hawking was an adult when he lost the ability to speak.” He has ALS, a degenerative neurological disorder. “He already knew how to use English to express himself. He already knew how to read. Ann was five or six when we started with her. What good is English text to a child who can't read yet? And if a child can't speak and can't move, how do you teach them to read? How do you know what they know, what they understand?”

McNaughton didn't know anything about children with dis-abilities when she began teaching at the Ontario Crippled Children's Centre (OCCC) in 1968. On her first day, as she was touring the center, she saw a little girl drop one of her crutches, and, she says, “I was about to run over and help her, but they held me back. ‘She has to learn how to get up,’ they told me.” After that McNaughton relied on the kids to tell her what to do—how to open leg braces, how to adjust a wheelchair—and she learned to focus on their capabilities and strengths.

But she wasn't sure what to do with the children who couldn't speak. “They had little boards with pictures on them—a picture of a toilet, a picture of some food, all needs-based pictures—I went through a year just asking them yes-or-no questions: ‘Would you like to do this? Would you like to do that?’ But they couldn't initiate anything themselves.” They seemed to understand what was said to them, and, more important, they seemed to have

something to say. “You could just tell with the twinkle in their eye or something.”

McNaughton started talking with some of the staff about trying to introduce reading to these kids. She and Margrit Beesley, an occupational therapist, went to the administration to ask for a half day to work just with the nonspeaking kids. “The administration agreed, and we were given a laundry room in the basement to try our experiment.” First, they needed to figure out what the kids knew and what they understood. They decided to try making up symbols that the kids could point to in order to express themselves (most of the kids, unlike Ann, were able to point), but it took them a long time to figure out how to symbolize more abstract concepts, so they decided to see whether someone already had a system of symbols they could use.

Their search led them to

Semantography

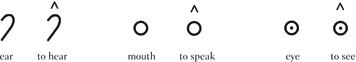

, Charles Bliss's eight-hundred-page book. He claimed that with the small number of basic symbols in his book, thousands of ideas could be expressed through combination. For example, this was how the words for emotions were expressed:

A noun could be made into a verb with the addition of an “action” symbol:

And adjectives could be made with the addition of an “evaluation” symbol:

Other words were derived from more complex types of combination:

This type of combinatorial system seemed promising. The children could only point to what they could reach from a seated position in their wheelchairs; they couldn't have a separate symbol for every word they might want to say. But if they could put two symbols together to create a third word, they could get more out of what fit in front of them.

Once McNaughton had taught the kids the meaning of a few symbols and showed them examples of how the symbols could be put together, she witnessed an explosion of self-expression. Kids whose communicative worlds had been defined by the options of pointing to a picture of a toilet, or waiting for someone to ask the right question, started talking about a car trip with a father, a brother's new bicycle, a pet cat's habit of hiding under the bed. Kids who were assumed to be severely retarded showed remarkable ingenuity in getting their messages across. When one little boy was asked what he wanted to be for Halloween, he pointed

to the symbols “creature,” “drink,” “blood,” “night”—he wanted to be Dracula. One particularly bright little girl named Kari took to this new means of expression with so much gusto that she could barely stand to be away from her symbols. When her father picked her up from school, she would cry through the whole car ride home, and could not be consoled until she was on the living room floor with her symbols, telling her family about the exciting events of the day.

McNaughton and the team of therapists she was working with took a picture of Kari, sitting in her wheelchair, surrounded by an array of symbols. Her eyes are sparkling, her smile is huge, and her dimples are adorable. When they finally tracked down Bliss in Australia, they sent him the picture. Before he received it, he later wrote, “I was resigned to my fate that I shall not see the fruits of my labours before I die. And then this picture, sent by Shirley, floated onto my desk. I can't describe the tumult of my thoughts. The heavens opened up and the golden sun broke through the darkened sky. I was delirious with joy.”

He immediately mortgaged his house in order to make the long trip to Toronto. Everyone was excited. When he arrived, there were meetings and talks and parties. Bliss told jokes and played the mandolin and showered everyone he met with over-the-top compliments. The children loved him; he juggled and sang and shouted his love for them at the top of his voice. When he found out that the speech therapist had recently lost her husband to diabetes, he shed tears of deep sorrow, raged at the injustice of her misfortune, professed his undying love for her, and proposed marriage.

The staff didn't quite know what to make of that. It seemed kind of sweet and funny at the time. He was seventy-five years old. He was exotic, Old World, an Austrian Jew who had survived

the war. He was effusive and emotional and not very Canadian. They stood back, amused but a little stunned. They had been hit by a personality tornado.

Near the end of his visit, Bliss gave McNaughton a copy of a book he had recently published,

The Invention and Discovery That Will Change Our Lives

. “We started to read it,” she told me, “and we all had a private meeting and we said the administration should never see this book. It was really something—about how the nuclear bomb is all a myth, how the Soviets killed Kennedy, and how teachers are to blame for the problems of the world, and how they are all cowards and sex perverts—we thought that if the administration sees this, they'll never let him come back.”