In the Land of INVENTED LANGUAGES (24 page)

Read In the Land of INVENTED LANGUAGES Online

Authors: Arika Okrent

At one point, Bliss was invited to give a lecture at a hospital in Sydney. Afterward, he fumed that only nurses had shown up. “Not one doctor!” he complained. He threatened to cancel an upcoming lecture at another hospital unless the organizers could guarantee that full, high-ranking medical doctors would be there. Instead, they canceled on him. Despite the documentary, the lecture invitations, the reporters knocking on his door, he felt ignored, disrespected. He was getting the attention of nurses, social workers, and teachers, when he wanted doctors, professors, and heads of state.

He was lucky to be getting any attention at all. Blissymbolics was not the only pictorial symbol language to emerge after World War II. There was Karl Janson's Picto (1957) and John Williams's Pikto (1959) and Andreas Eckardt's Safo (1962). No one was using those languages for anything.

Bliss had come to adulthood in interwar Austria, where a man was nothing without a title. He longed to inspire the same awed respect in others that he had felt when, as a poor, provincial nobody, he encountered the Herr Doktors, Herr Ingenieurs, and Herr Doktor Doktor Professors of Vienna. He thought people didn't listen to him because he lacked the right titles, and so he never ceased trying to get those titles. He wrote to every university in Australia, asking to be granted a professorship, or at least

a Ph.D., on the basis of his success with the Toronto program, but none responded. (He did finally purchase a mail-order Ph.D., shortly before his death.)

The titles wouldn't have done him any good. While Bliss was traveling around giving interviews and lectures (“nurses'” lectures though they may have been), one Doktor Doktor Professor John Wolfgang Weilgart was unsuccessfully trying to get someone, anyone, to pay attention to his universal language.

Weilgart was a professor of psychology (at Luther College, in Iowa) with two Ph.D.'s when he first published his

aUI: The Language of Space

, in 1968. Weilgart was also from Austria, but had grown up in much more elevated circumstances than Bliss had. His grandfather was a Hungarian nobleman of some sort. His father, Hofrat Professor Doktor Doktor Arpad Weixlgärtner, was the director of the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. His uncle Richard Neutra was a famous architect. They lived in Schoenburg Palace for a time. They socialized with Freud and other luminaries of turn-of-the-century Vienna.

As a boy, Weilgart had visions of winged beings who came from the stars to deliver a message of peace. When he told his parents about his visions, they took him to a psychiatrist, who diagnosed nothing more than a high IQ but warned him that he should speak about such visions only as “dreams” or “poems.” Since he seemed to be obsessed with words and sounds and meaning, his father encouraged him to get a degree in languages and philology, which he did, completing his dissertation a few months before the outbreak of World War II. He spent the war in the United States, teaching German, Spanish, Latin, and French at various schools and colleges in Oregon, California, and Louisiana. After the war, he returned to Europe and got another degree, in psychology.

He began teaching at Luther in 1964, where he completed his book on aUI. It begins with a poem about a boy who is visited by a kindly “Spaceman.” The Spaceman wants to transmit the wisdom of his beings to the people of Earth, but cannot do it through the languages of Earth, because “if we learnt your millions of words, we would be infected by your warped way of thinking.” So he teaches the boy the language of space.

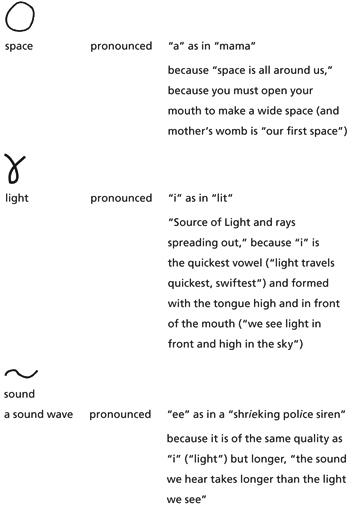

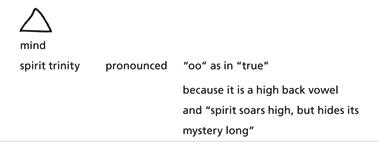

In aUI, all concepts are derived from a set of thirty-three basic elements that have not only a motivated pictorial representation but a motivated sound representation.

The word aUI is formed by combining “space” (a), “mind” (U), and “sound” (I) and means “the language of space” because language is “when your mind sounds off.”

Weilgart's aUI was supposed to serve as a neutral international language, and a cure for diseases of the mind caused by language. Weilgart claimed it was a language of cosmic truth that could bring about peace, dissolve selfishness, and align the conscious and subconscious mind. He developed a psychotherapy technique where he had patients translate words into aUI, in order to help them better understand the meaning of the concepts that troubled them. He worked for a time with drug addicts in the navy's drug rehabilitation program, where, according to a recommendation letter from his boss, “meditations in these ‘Elements of Meaning’ superseded the desire for drug experience.”

Despite his credentials, Weilgart could not get anyone to listen to him. His self-published books were full of bizarre line drawings, poems, and mystic philosophizing. Weilgart's bewildered colleagues at Luther tolerated him in their polite Lutheran way, while the administration pushed him to the margins as much as they could. He was asked not to peddle his books on campus, so some summers he left his family behind and toured across the country in a van, a prophet of the cosmos, stopping people on the street to tell them about aUI. He wrote to everyone he could think of, trying to drum up support for his project—Kurt Waldheim, B. F. Skinner, Pearl Buck, Albert Schweitzer, Noam Chomsky, the Shah of Iran. He asked Johnny Carson to make an announcement on his show. He asked Kurt Vonnegut to introduce aUI “in some of your stories … by letting e.g. a space-man speak in this language (I would be glad to translate any sentence into it).” In each case he molded his approach to what he thought the recipient might want to hear, often to embarrassing effect. He began his letter to Margaret Mead by appealing to her womanhood (“it takes a woman to teach the mother-tongue … I see you, dear Mrs. Mead, as prophetess of motherhood”), and his letter to Harry Belafonte describes aUI as a “language without prejudice” and dwells on the unfortunate sound associations of the word “niggardly.”

He wrote to some of the same people Bliss did, and at some point one of them must have informed Bliss about Weilgart's project. Bliss wrote to him immediately, but kept it polite. After all, here was a Doktor Doktor Professor who didn't dismiss the idea of a universal symbol language but rather embraced it. Perhaps he could convince Herr Professor to support Blissymbolics instead. Weilgart wrote back an equally polite letter, expressing admiration for Bliss's ideals but not saying much about his project

beyond that he thought it was “a most interesting endeavor.” The rest of Weilgart's letter was a slyly aggressive description of his background—the illustrious relatives, the degrees he had received, his experience being diagnosed with an abnormally high IQ—every detail no doubt another knife twist in Bliss's fevered knot of insecurity.

Bliss received Weilgart's letter in April 1972, just before his first trip to Toronto. He was about to experience the peak of his career, and Weilgart, who wasn't being written about in Time magazine or anywhere else that Bliss knew of, soon seemed a much diminished threat. Bliss shifted his attention to other problems.

The Catastrophic Results

The Catastrophic Resultsof Her Ignorance

B

oth Bliss and Weilgart claimed their languages expressed the fundamental truth about things. They also claimed that because they used “natural” symbolism—forms that looked like, or sounded like, the things they referred to—their languages were transparent, able to be universally understood. However, their ideas of what was “true” and what was “natural” were completely different.

For example, Bliss's symbol for water is Weilgart's symbol for sound. For Weilgart, water is not a primitive but a complex concept:

The explanation is that water is the liquid (

jE

, matter that “stands even, when at rest”) of greatest quantity.

For Bliss, sound is not a basic primitive but a complex concept, —an ear on top of the earth—that “indicates a vibration of air molecules.”

—an ear on top of the earth—that “indicates a vibration of air molecules.”

Weilgart's image of water refers to how it looks when it is level, and Bliss's refers to how it looks when it has waves in it. Bliss's image of sound refers to the organ that receives it, and Weilgart's refers to the “wave” physics of its transmission. Who has the truth? Whose representation is more “natural”?

If two men who come from the same place and speak the same language can't even agree with each other about the “true” representation of anything, how can either one of them stake a claim on universality? The act of understanding a sentence in either system is an act of figuring out one man's opinions, of guessing one man's intentions. These languages are about as opposite of universal as you can get. They require mind reading, a task considerably more difficult than, say, learning French.

Imagistic symbolism can transmit meaning, but in such a vague and open-ended way that it makes a terrible principle on which to build a language. This is why there are no languages, and no writing systems, that operate on such a principle.

This includes sign languages, which are assumed by many to be a sort of universal pantomime. In fact sign languages differ considerably from country to country, so much so that in the 1950s, the newly formed World Federation of the Deaf assigned a committee to look into the matter of developing an auxiliary sign standard that could be used at the federation's world congress and other international deaf events. The result, finally published in 1975, was Gestuno, the Esperanto of sign language.