In the Land of INVENTED LANGUAGES (25 page)

Read In the Land of INVENTED LANGUAGES Online

Authors: Arika Okrent

Sign languages differ for the same reason spoken languages

differ—they evolved naturally, from communities of people interacting with one another. Wherever deaf people have come together in groups, whether because they lived in places with a high incidence of genetic deafness or because they were brought together in institutions or schools, they have spontaneously developed a sign language. These languages may have their origins in gestures of “acting things out”—a type of vague,

partial

communication—but over time set meanings developed, means of marking grammatical distinctions became fixed, and they turned into real languages, systems of

full

communication.

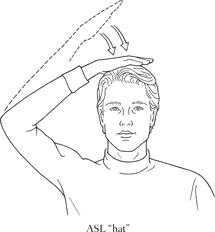

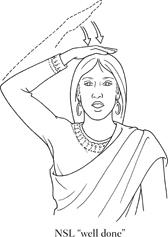

Signs mean what they mean by conventional agreement, and different communities of signers have different agreements. In American Sign Language (ASL), for example, the sign below means “hat,” not because it looks like a hat being placed on the head, but because the community of users of ASL agree that it means “hat.”

Users of Nepali Sign Language (NSL) have a different agreement: a sign that looks exactly the same means “well done.”

Does this sign “look like” a pat on the head for a job well done or a hat being placed on the head? It doesn't really matter. What matters is that Nepalese signers agree that it's the sign for “well done” and American signers agree that it's the sign for “hat.” The meaning isn't dependent on the imagery.

Many signs do, in some sense, “look like” what they mean, but just because you can come up with an explanation for why a sign has the form it has does not mean the sign gets its meaning by virtue of that explanation. This is true for spoken words as well. The word “breakfast,” for example, has a motivated form, inspired by the idea of breaking a fast, something you do in the morning when you eat after going eight hours or so without food. But “breakfast” does not mean “to break a fast.” It means “morning meal,” or, in the case of “breakfast anytime” diners, a meal consisting of eggs or pancakes. “Breakfast” gets its meaning from the way “breakfast” is used, not from the fact that it was once formed from the words “break” and “fast.” (Therefore it doesn't matter that the “break” in “breakfast” has come to be pronounced

“brek.” You don't need to recognize the motivation for the word in order to understand it.)

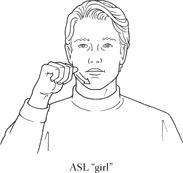

Likewise, the ASL sign for “girl,” which traces a line on the cheek, gets its meaning through conventional usage, not from the fact that it was motivated by the image of a bonnet string. (Therefore it doesn't matter that girls no longer wear bonnets.)

Gestuno, like most international language schemes, was a big flop. The committee had drawn from existing sign languages, trying to pick the most iconic signs, but without favoring any one country too much. Deaf people complained that the signs that had been chosen weren't easy enough to understand. Furthermore, Gestuno was only a lexicon, not a grammar, so there were no explicit guidelines for putting sentences together. At the 1979 World Deaf Congress in Bulgaria, the first congress to provide Gestuno interpretation of the presentations, the interpreters simply stuck Gestuno signs into (spoken) Bulgarian sentence structures (sign languages do not follow the same word order or grammar as their surrounding spoken languages). No one understood what was going on, and Gestuno never recovered from the fiasco.

Something else took its place—a spontaneous sort of pidgin

signing now called International Sign. It had actually been around long before Gestuno. Whenever deaf people of different sign language backgrounds get together at international events (like the Deaf Olympics, which began in the 1920s), they quickly find a way to communicate with one another. They sign more slowly, gesture, and repeat information in multiple ways, and pretty soon they come to a sort of miniature, incomplete, conventional agreement. They negotiate a standard, but one that is less reliable than any full sign language.

However, that standard, and a pretty good level of communication, is achieved far more quickly and easily than it ever could be between people who speak different

spoken

languages. That is because while the iconic imagery is not the primary principle on which sign languages depend, it is undeniably there, and it has the potential to be exploited. Spoken languages have this potential as well (something can last a “long” time or a “loooooooong” time) but a whole lot less of it.

Imagery, in signs or in symbols, isn't suitable for communication on its own. It must be interpreted, its meaning guessed at. But in a situation where the guesses can be constrained, where two people can use context and feedback from each other to put a limit on the possible interpretations, it is extremely useful. The teachers at the OCCC understood this, and what they did with the children was set up just such a situation. When a child wanted to say “dream” but did not have a symbol for it on her board, she pointed to “sleep + think.” Her teacher guessed from the context that she meant “dream,” and the child confirmed that guess. If a child tried a combination and the teacher guessed wrong, the teacher could take another guess, or the child could try a different approach. Communication had always been a guessing game for these children, but before Blissymbols they had no way to constrain

the guesses. If a child had needs-based pictures to point to, he might have tried to say “dream” by pointing to a picture of a bed. Then the adult would ask, “Do you want to go to bed? Do you want to get your pillow? Is there a problem in your bedroom?” and the child would have no power to direct the line of questioning. When the children learned Blissymbols, and a method for representing abstract concepts through combination, they finally had a way to actively put limits on interpretation.

And this changed their lives tremendously. On my Toronto trip, I asked another of Shirley's former students how he used to communicate before he learned Blissymbolics. He typed out a one-word answer on his computer: “Kick.”

Though Blissymbols was a huge improvement over what was available to the children before, it was still not good enough. The children could communicate about almost anything with their teachers, parents, and others who were familiar with the special mechanics of negotiated agreement that Blissymbols required, but they couldn't do this with just anyone. They had access to communication, but not full access. They had a very useful tool, but not a language.

So the OCCC staff modified and adapted Bliss's system in order to make it serve as a bridge to English. They added the alphabet to the symbol boards, so the kids, before they had fully learned to spell, could constrain a symbol by pointing to the first letter of the word they intended. Teachers using the symbols in other countries made adjustments in accordance with the requirements of their spoken languages: In Hungary, they changed the order of the symbols to reflect Hungarian word order and added symbols for grammatical markers as needed. In Israel, they wrote the symbols from right to left. All of these adjustments infuriated Bliss, because he thought he had invented a universal language.

After the OCCC administration told Bliss he was not welcome anymore, his level of interference increased tenfold, and he started threatening lawsuits. Twice, legal agreements were reached where he granted the center rights to use his symbols (under the terms of one agreement, the center was required to mark all symbols in its publications that he had not personally approved with a ), but he always found an excuse to break the agreements and begin fresh attacks on its progress.

), but he always found an excuse to break the agreements and begin fresh attacks on its progress.

He sent an open letter to all institutions in Europe that worked with disabled children in order to “voice my flaming protest against the machinations and perversions of my work by an irresponsible and irrational woman, Mrs. Shirley McNaughton.” He wrote a pamphlet called “My Terror of Toronto” and sent it to the government, the press, and anyone else he thought would listen. McNaughton started getting random “who do you think you are?” letters from strangers. At the same time, Bliss wrote her letters telling her how much he loved her and hoped they could “go on to a greater glory together.” After he viewed the

Mr. Symbol Man

film, he sent her a telegram:

HAVE SEEN FILM EXTREME CLOSEUP OF YOU DEADLY TO HOLLYWOOD BEAUTIES BUT YOU CAME OUT MORE BEAUTIFUL THAN EVER HAVE FALLEN IN LOVE WHAT AGAIN YES AGAIN LOVE TO BOB KEVIN DAVID

Bliss was desperate for respect, but he was more desperate for love. He was genuinely shocked and hurt when people got angry at him, or cut him out of their lives, despite the fact that it was his own irrational behavior that drove them away. He saw himself as a charmer, an entertainer, a selfless lover of humanity. In his oftrepeated and unlikely account of his release from Buchenwald,

he had melted the hearts of his Nazi prison guards with his mandolin playing. It was crucial to his view of himself that he believe in the magical power of his generous spirit.

So, often, when he sensed he had gone too far, he made an effort to win back love. But it never lasted very long. Sometimes the very next day after an apology, a flattery, a plea for pity and understanding, he would find himself fueled by a fresh wave of indignant anger, and the tirades would start up again. He couldn't help himself.

This was his holiday greeting the next year:

A MERRY CHRISTMAS TO YOU, PEACE ON EARTH AND GOOD WILL TO ALL MEN

. Yes, Good Will to all Men, but not to a woman, Mrs. McNaughton. She's trying to kill me, make me drop dead so she can take over, but im not going to. Are you protecting your fair maiden, well she's not fair. She has black hair and a black mind.

At one point, Shirley almost resigned, but found she couldn't leave her students behind. Instead, she accepted dealing with Bliss as another part of her job. He still came back every spring, and she still greeted him warmly. Despite everything that had happened, she maintained respect and admiration for him, and really did want to please him. Her equanimity in the face of it all resulted in a workable but absurd situation, as captured in one of her letters to Bliss.