Isis

Authors: Douglas Clegg

| Isis |

| Douglas Clegg |

| Vanguard Press (2009) |

Table of Contents

For

Mindy

Mindy

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

With thanks to Raul Silva, M. J. Rose, Glenn Chadbourne, Simon Lipskar, Francine LaSala, Roger Cooper, Amanda Ferber, Georgina Levitt, and all of Vanguard Press.

FOR READERS

Be sure to go to

www.DouglasClegg.com

for the free, private newsletter and get instant access to exclusive extras and treats, including novels, novellas, stories, screensavers, and more.

www.DouglasClegg.com

for the free, private newsletter and get instant access to exclusive extras and treats, including novels, novellas, stories, screensavers, and more.

Part One

The Window

Jack, swing up, and Jack swing down

Up to the window, over the ground.

Swing over the field and the garden wall—

But watch out for Jack Hackaway if you should fall.

—Nursery rhyme, 1800s

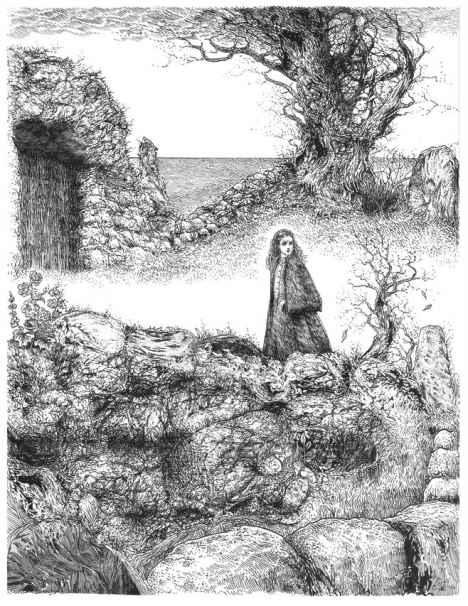

“Beware a field hedged with stones,” our gardener, Old Marsh, told me in his smoky voice with its Cornish inflections, as he pointed to the land near the cliff. “See there? The hedge holds in. Will not let out. Things lurk about places like that. Unseen things.”

A house, I suppose, is a stone-hedged field.

A tomb, as well.

The place where the stone-hedges ended, as they grew round our house and the gardens, was an old cave entrance that had been turned into a mausoleum beneath the ground, carved out for centuries for the bones of my ancestors.

The locals called it the Tombs, although it was much more than merely a series of subterranean burial chambers. It had been carved from rock by the local miners for some early Villiers ancestor and had been used just two years before my birth, when my grandmother had died. Her coffin was sealed up in granite and plaster within the Tombs, and there were spaces for other Villiers to come. My mother made me swear that I would never allow her to be buried there. “I don’t like that place,” she told me. “It’s cold and horrible and primitive. Put me in a churchyard with a proper marker. Do you promise me?” Certain that her death was years away, I promised her whatever she asked. I coaxed a smile from her when I demanded that upon my own death, she have the rag-man cart me away to the rubbish pile.

What lay below the Tombs had once been a sacred site to the Cornish people, more than a thousand years earlier. It had been a cave, leading down the cliff-side through a series of narrow passages out to sea. It was believed to be an entrance to the Otherworld—the Isle of Apples, it was sometimes called—where a stag-god and a crescent-moon mother goddess ruled.

There had been a legend, once, of a Maiden of Sorrow, who had traveled deep in the earth to the Isle of Apples to find her lover who had died a terrible death in a distant battle. When she had returned, she brought him with her and held his hand as they emerged from the winding caves into the sunlight. But when others saw the couple, they cried out in terror—for her lover’s eyes were black as pitch, and he had no mouth upon his face, just a seal of flesh as if he had not formed completely upon his journey back to the land of the living. The villagers knew he was not meant to be among them, yet the Maiden would not allow him to return to the earth. The legend went that the Maiden lived with him there at the edge of the sea, but he could not speak, nor did his eyes return to life, nor could anyone look him in the eye, lest they be driven mad from seeing the Otherworld reflected in his glance.

When someone in the nearby village was near death, the Maiden’s lover would appear at their doorway and seek entrance, as if trying to find his way back to his soul, which had remained on the other side.

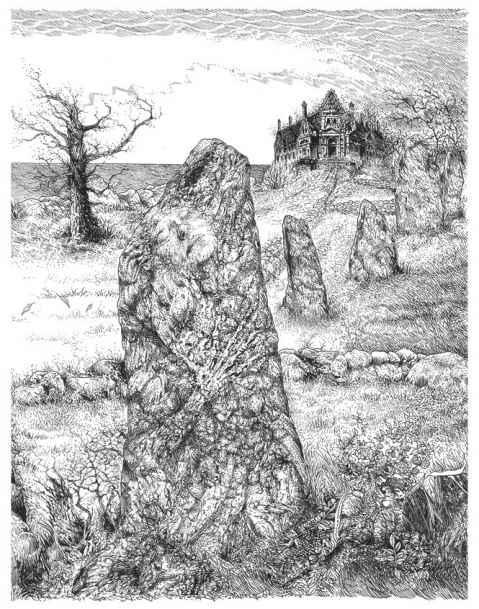

There was also a large round granite stone in the field at the edge of the sunken garden, not ten paces from the Tombs. Called the Laughing Maiden, it was believed that once in early times of the Christians, another maiden went out and laughed at the priest on Sabbath day and was turned to stone there.

I went to this stone as a girl with our gardener, who believed all the old tales. Old Marsh was thought of as the local color—the crackpot old-wives-tale man of the earth who believed all the old stories and would walk backward around a graveyard to avoid upsetting the dead. He had been known to plant sheep-nettle at the stables when one of the horses had gotten sick, “to keep out bewitchments,” he’d say quite proudly. He knew a story for every stone, every fountain, every plant, and every tree at Belerion Hall. Old Marsh took it all seriously, and he warned me against upsetting spirits by changing the old gardens too much. “They like their flowers as they like them,” he said when I had been uprooting the weed-like milk thistle. “Bad luck to do that, for the saying goes, ‘Set free the thistle and hear the devil whistle.’”

At the Tombs, he gave me the most serious advice. “Never go in, miss. Never say a prayer at its door. If you are angry, do not seek revenge by the Laughing Maiden stone, or at the threshold of the Tombs. There be those who listen for oaths and vows, and them that takes it quite to heart. What may be said in innocence and ire becomes flesh and blood should it be uttered in such places.”

Other books

Mila's Tale by Laurie King

City of Dragons: Of Flesh and Blood by Wilder, Adrienne

Abendau's Heir (The Inheritance Trilogy Book 1) by Jo Zebedee

Crowning Fantasy Book 1 by Coral Russell

Leviathan by Scott Westerfeld

The Bishop's Pawn by Don Gutteridge

Eternity by Heather Terrell

Souvenir of Cold Springs by Kitty Burns Florey

Into the Void: Star Wars (Dawn of the Jedi) by Tim Lebbon

Broken and Screwed by Tijan