Isis (2 page)

Authors: Douglas Clegg

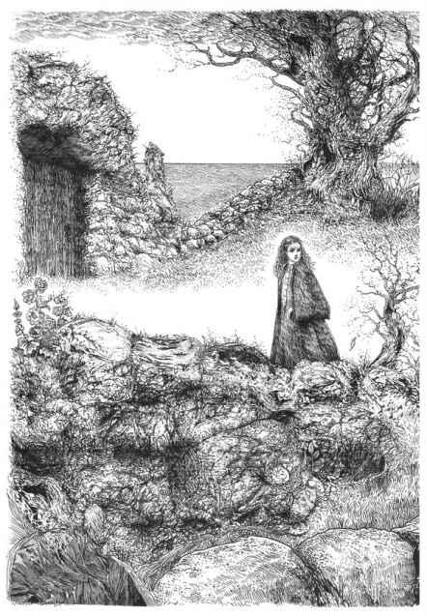

I looked upon the rock chamber with its small double doorways and its chains and lock, a ruins more than a mausoleum, sunken into the grassy earth with a view of the wide gray sea beyond it, and remembered such stories.

I did not intend ever to cross its threshold.

I was born Iris Catherine Villiers, and in the days before we came to Belerion Hall, my parents were still in love with each other. My older brothers—the “twin Villiers” as old Mrs. Haworth would later call them—Spencer and Harvard, and my eldest brother, Lewis (whom I rarely saw once we had left our first home), made up the children. To tell them apart, Spence parted his hair on the left, and Harvey, on the right. Harvey had a birthmark behind his ear, while Spence had none. Spence smelled, in the summer, distinctly of dirt and pond water, while Harvey had a fragrance as if he’d rolled in lavender.

I could tell them apart from the moment my memories began—for Harvey had always been pure warmth and gentleness whereas Spence was casually cruel and often cold, though perfectly nice in his own way. At my birth, Lewis was six, and Harvey and Spence were three. I did not have a moment in my life when one of them did not occupy my time in some way, whether for good or ill. Of the three, Harvey loved me from the moment I could remember. I loved him in the sisterly fashion for he was my protector in many ways from the rough-and-tumble of other children, and from his own twin, who resented the new baby in the family.

My earliest memories were of delight and love. We had a happy, bright, and beautiful mother who hailed from Chicago and had been, briefly, an actress and then a pianist. She had married my father, a British citizen, when they ran into each other outside of the Carthage Club in Manhattan before lunch. They fell in love over soup and roast beef at the Bellamy on Fifth Avenue, spoke of the future after cocktails at the “26,” and were married before City Hall had closed, much to the chagrin of my mother’s parents. My mother never again played the piano, and her only acting would be later, in local amateur theatricals that often thrilled me, for they seemed to be made of magic and stardust.

I was born in the summer cottage at Fisher’s Island that my American grandparents had given my parents as a wedding gift. I grew up an island girl, rarely ever going to the mainland, for I had a tutor and nanny at our house. I walked barefoot nearly all the summer, though my father called my mother “primitive” for allowing her children such immodesty.

My brothers took up slingshots when I was five. Harvey, as a joke, aimed at a bird in a tree, but when he’d shot it, he felt terrible that the bird had been hit and fell to the earth. We both ran to it, and Harvey lifted it into his hands and kissed it. He let it go and it flew off. “It was only stunned,” he said, and I told him, “Promise me never to do that again.” He promised. I made him promise a second time. We watched the bird fly off across the pink summer twilight, and then we went to bury his slingshot forever.

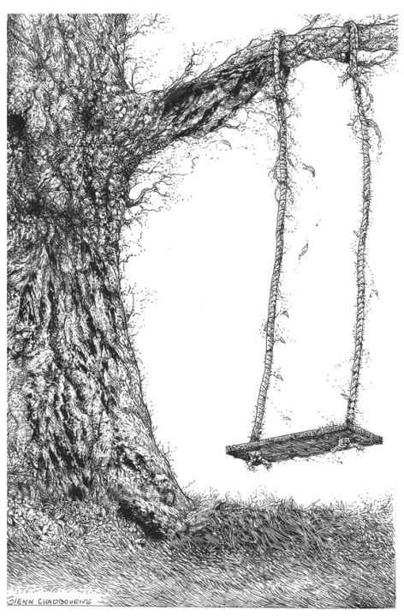

My brothers parted for their boarding school during the week and then returned Friday evenings to spend the weekends on the island. We played all the games of childhood, and when I was afraid to go on the swing that hung from the oak tree in our yard, Harvey had told me, “But we’re the Great Villiers Brother-and-Sister Trapeze Act!”

He would beat his chest and call out, “The greatest circus on the island! Come one, come all, to the Great Villiers Trapeze Brother-and-Sister Act!” And then he’d swing me up in his arms and rock me as if I were in a cradle. Gingerly, he would step onto the low swing, holding onto me with one hand while he squatted down upon the plank. We would swing up and down for hours, and he never once dropped me or let me go.

As we both became more comfortable with the Great Villiers Trapeze Brother-and-Sister Act, he’d swing me around and when I grew scared again, he’d say, “Close your eyes and count to ten, and when you open them, you’ll be on the ground.” And so we began to do minor acrobatics, which scared my mother half to death, for he might stand on the swing and lift me up to his shoulders while we flew out over the grass. I smelled summer lavender upon him, and sometimes I smelled the sea, too, for it was just in sight. I had no other friends on the island, and my other brothers paid no attention to me.

Harvey taught me the nursery rhymes our father had taught him when he had been my age, including the swinging rhyme about Jack Hackaway. “Jack Hackaway is a little troll who takes children to the goblins when they fall,” he said, and now and then to scare me a little he might say, as we swung, “Who goes there? Jack Hackaway, is that

you

?”

you

?”

Sometimes I felt as if I were flying with wings on when we swung together. He always treated me as if I were the special one in the family. I loved those memories, and I cherish them even now.

By my seventh year, my father had been called to Burma by the British government, for there was a war and he was a trader in wars. So many wars came and went while I was a child that even in later years, I barely remembered what my father looked like, or how he spoke, for it was like remembering a haunting stranger seen once in a crowded train station and then never again.

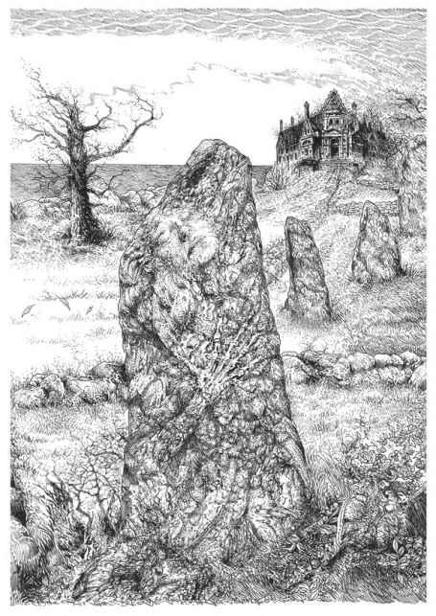

My mother and my older brothers and I were packed off to my father’s ancestral home across the sea to watch over his own father, who was close to death. We moved into Belerion Hall, traveling from my beloved cottage off the Long Island Sound to the rocky cliffs of the furthest perch of Cornwall.

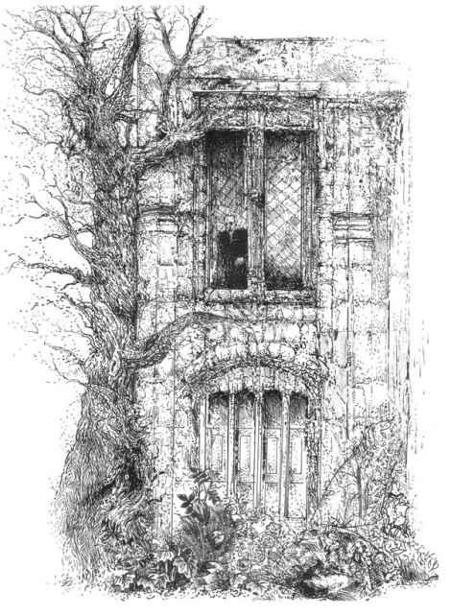

My first sight of the place was painful. I saw in its slate-gray curtain of rain nothing but a large prison, so unlike the delicate, wispy cottage I considered our true home, with its azalea and rhododendron bushes all around and the honeysuckle in midsummer. This new home had dead gardens that brimmed with the skeletons of briars, while moss slickened its rusty stones. Belerion Hall seemed like a millwork factory that had closed years ago, a great turgid red brick monolith to an unhappy era.

If Belerion Hall had the puritanical face of a factory, then my grandfather could best be described as the Gray Minister, which is what my brother Harvey named him immediately after our first encounter. “The Gray Minister lurks,” he’d whisper to me as I giggled. “He listens at keyholes.” Or after supper, when we played charades in the nursery, Harvey would make a signal in the air with his hands as if waving and say, “The Gray Minister comes a-tap-tapping.” This got the both of us in trouble when Spence told our grandfather of the nickname, and the elderly man came at Harvey with his gold-tipped cane, leaving my brother with bloodied trousers. Harvey had protected me, pushing me behind one of the many curtained alcoves of the corridors so that I might not be found for punishment.

Our grandfather was a tall, gaunt man of seventy, with a white wisp of beard like a goat, and a long pale face that rose up to meet the bits of peppery scrub hair left him upon his scalp.

He had eyes that always seemed red and smudged with sleeplessness, and his lips were thin and drawn back over an uneven row of teeth. He seemed perpetually smeared with a slight layer of coal dust, as if he’d been rooting around in the cellars. He rarely wore anything other than a gray coat, and beneath this, a stiff white shirt with a heavy white collar, both of which the maid had to press daily. His shoes and trousers were gray, as well, and he carried the Bible with him, though it was worn and its binding crackled and threatened to turn to dust each time he opened it.

“To spill thy seed,” he often warned Spence and Harvey, “is to invoke the wrath of God.”

To me, he would say (even when I was eleven or twelve), “Woman, thou art a temptation to Man. Clean thyself and thy thoughts. Scrub the unholy places of thy body, and bind thy flesh that it may be secret from our eyes.”

His mania did not limit itself to us. He waggled his finger at my mother, declaiming verse and psalm and invoking the deity as if the Lord were his personal servant. My mother had enough, and by the end of our first year at Belerion Hall, she locked her father-in-law into the North Wing of the estate. While servants might go there to care for him, we children could only see him on Christmas and on his birthday.

Still, we heard his shouts of wrath and brimstone and Babylon from the windows of the North Wing, often late into the night. The Gray Minister stood there in the smear of light from the flickering lamp at the window and cried out ungodly things upon our heads or upon the heads of the kings of the world.

“When your father returns,” my mother told me as she tucked me in one night when I had been agitated over my grandfather’s caterwauling, “we will find your grandfather a proper place. He is not himself. His memories are gone. This ceaseless rain must also prey upon him. We must pity him.” She kissed me on the forehead, and we said our prayers together as my grandfather continued crying out at the top of his lungs from the windows of the North Wing, “The Whore of Babylon rides upon the King of Hell! I have seen her! I have seen her! The Great Harlot! The Devil’s Dam!”

I loathed the place in the rainy times. My mother had a peculiar ailment that seemed part sorrow and part silence and grew worse when the weather grew rough and cold. In the winters, she took to her bed for weeks at a time, only seen by a nurse and the girl who took her supper. My mother’s headaches increased then, and she had begun getting deliveries in the afternoon from a druggist in the village whose boy dropped off two packages of tincture of laudanum, three times a week; and if the boy on the bicycle did not come, Mrs. Haworth sent Percy, our gardener’s son, into the village for a small bottle of

Dr. Witherspoon’s Vita-Health Tonic

, which smelled distinctly of rum.

Dr. Witherspoon’s Vita-Health Tonic

, which smelled distinctly of rum.

Other books

The Adjustment League by Mike Barnes

Cold Night (Jack Paine Mysteries) by Al Sarrantonio

All in a Don's Day by Mary Beard

Taydelaan by Rachel Clark

Blaylock, James P - Langdon St Ives 02 by Lord Kelvin's Machine

Werewolf Rebel Tamed (Werewolf Romance) by Fox, Michelle

The War Hound and the World's Pain by Michael Moorcock

The Gold Cadillac by Mildred D. Taylor

Blind Trust by Susannah Bamford

Spoken For by Briar, Emma