Jacky Daydream (17 page)

Authors: Jacqueline Wilson

‘I’ll tell you later,’ Biddy hissed – and fair enough, she did.

We had our jaunts up to London to look at the dolls and beg for Mandy photos. We also went to the big C & A clothes shop in Oxford Street to look at the party dresses. I hankered after the flouncy satin dresses – bright pinks and harsh blues and stinging yellows – but Biddy thought these

very

common. She chose for me a little white dress with delicate stripes

and

multi-coloured smocking and a lace collar. I still preferred the tarty satin numbers, but I loved my demure pretty frock and called it my rainbow dress.

I

didn’t

love the trying-on process. Biddy was always in a hurry, and if there was a long queue for the changing room, she pulled off my coat and tugged my dress over my head, leaving me utterly exposed in my vest and knickers. I protested bitterly, scarlet-faced.

‘Don’t be so silly,’ said Biddy. ‘Who on earth would want to look at

you

?’

She was forever putting me in my place and reminding me not to get above myself. If I got over-excited at a dance or a party and joined in noisily with all the other children, Biddy would seize hold of me and hiss in my ear, ‘Stop showing off!’ Yet this was the same mother who wanted me to turn into Shirley Temple and be the all-singing, all-dancing little trouper at a talent show.

She had no patience with my moans and groans but she could be a very concerned mother at times. When I was seven or eight, I developed a constant cough that wouldn’t go away even when she’d spooned a whole bottle of Veno’s down me. She was always worried about my chest since my bout of bronchitis so she carted me off to the doctor.

He didn’t find anything seriously wrong with me. I think now it was probably a nervous cough, an

anxious

reaction to the tension at home. The doctor advised Sea Air as if I was a Victorian consumptive.

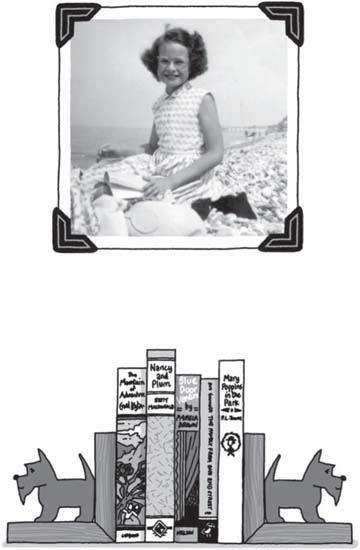

‘Sea Air!’ said Biddy.

We lived seventy miles from the seaside and we didn’t have a car. But she took it on board valiantly. She somehow managed to find the money to take me on Saturday coach trips to Brighton right the way through the winter. We mooched round the antique shops in The Lanes and had a cup of tea and a bun in a café and walked up and down the pier and shivered in deckchairs while I breathed in the Sea Air. It worked a treat.

You certainly didn’t go to Biddy for tea and sympathy, but she was brilliant at getting things done. She was almost too good when it came to school projects. I remember a nature project when we were told to collect examples of different leaves. This was a simple enough project. I could easily gather up a handful of leaves on my way home from school. But when I casually mentioned it to Biddy, she snapped into action. She dispatched Harry and me to Richmond Park on Sunday morning and instructed us to find at least twenty different samples. We did as we were told. Biddy spread leaves, berries, nuts – goodness knows what else – all over the living-room table. It was our job to identify each example with an inadequate I-Spy spotters’ guide,

her

job to mount them magnificently on special white board. She

labelled

them in her exquisitely neat handwriting, then covered the finished work of art with protective cellophane.

My arms ached horribly carrying this confection like a splendid over-sized tray on the half-hour walk to school. The other children claimed – justifiably – that I’d cheated. The teacher seemed under-impressed with Biddy’s showy display. I had enough sense to lie like crazy when I got back home, telling Biddy that I’d been highly praised and given top marks for my project.

She particularly excelled at Christmas presents. She had no truck with Father Christmas, not seeing why he should get the kudos when she’d done all the hard work and spent the money. I didn’t feel at all deprived. I didn’t care for Father Christmas either. I hated having to queue up to have my photo taken with this overly jolly old gent in Bentalls department store at Christmas. Once he’d peered myopically at my short-cropped hair and given me a blue-wrapped present for a boy.

We didn’t go in for stockings at Cumberland House. Biddy organized a special Christmas bumper

box

stuffed with goodies wrapped in bright tissue paper. There might be a Puffin paperback –

Ballet Shoes

or

The Secret Garden

or

The Children Who Lived in a Barn

. There would definitely be a shiny sheath of Mandy photos. I’d hold them

carefully

and very lightly trace her glossy plaits, smiling back at her. There could be crayons or a silver biro, and red and blue notebooks from Woolworths with the times tables and curious weights and measures printed on the back. I never encountered these rods, poles and pecks in my arithmetic lessons, and didn’t want to either. There would be something ‘nobby’ –Biddy’s favourite word of approval for a novelty item like an elephant pencil sharpener or two magnetic Scottie dogs that clung together crazily.

These were all extras. I always had a Main Present too. Hard-up though she was, Biddy never fobbed me off with clothes or necessities like a school satchel or a new eiderdown. My Main Present was a doll, right up until I got to double figures.

They were always very special dolls too. Sometimes I knew about them already. Once I saw a teenage rag doll with a daffodil-yellow ponytail and turquoise jeans in a shop window in Kingston and I ached to possess her. Biddy didn’t think much of rag dolls but she could see just how much I wanted her. We’d go to look at her every week. I went on and on wanting her. Then one Saturday she wasn’t there any more.

‘Oh

dear

,’ said Biddy, shaking her head – but she could never fool me.

I pretended to be distraught – and probably didn’t fool her either. I waited until I was on my own in the flat, then hauled one of the living-room chairs into my parents’ bedroom, opened Biddy’s wardrobe door, and clambered up. There on the top shelf was a navy parcel, long but soft when I poked. It was the teenage rag doll, safely bought and hidden away.

I’d go and whisper to her at every opportunity, imagining her so fiercely she seemed to wriggle out of her wrapping paper, slide out from the pile of Biddy’s scarves and hats, and climb all the way down her quilted dressing gown to play with me. My imagination embellished her a little too extravagantly. When I opened her up at long last on Christmas Day, her bland sewn face with dot eyes and a red crescent-moon smile seemed crude and ordinary. How could

she

be my amazing teenage friend?

Another Christmas I had a more sophisticated teenage doll, a very glamorous Italian doll with long brown hair and big brown eyes with fluttering eyelashes. She wore a stylish suedette jacket and little denim jeans and tiny strappy sandals with heels. When I undressed her, I was tremendously impressed to see she had real bosoms. This was a world before Barbie. She must have been one of the first properly modelled

teenage

dolls. I was totally in awe of her.

I had been reading in Biddy’s

Sunday Mirror

about Princess Ira, a fifteen-year-old precociously beautiful Italian girl who was involved with a much older man. I called my doll Ira and she flaunted herself all round my bedroom, posing and wiggling and chatting up imaginary unsuitable boyfriends. I shuffled after her, changing her outfits like a devoted handmaid.

I had one real china doll from Biddy. She saved up ten shillings (fifty pence, but a fortune to us in those days) and bought her from an antique shop in Kingston. She wasn’t quite a Mabel. She had limp mousy hair and had clearly knocked around a little. She was missing a few fingers and she had a chip on her nose but she still had a very sweet expression. I loved her, and her Victorian clothes fascinated me – all those layers of petticoats and then frilly drawers, but she was difficult to

play

with. She was large and unwieldy and yet terrifyingly fragile. I could move her arms and legs but they creaked ominously. I brushed her real hair but it came out in alarming handfuls, and soon I could see her white cloth scalp through her thinning hair.

I

wish

Biddy had been fiercer with me and made me keep her in pristine condition. She’d be happy living in my Victorian house. I’d never let some

silly

little girl undress her down to her drawers and comb her soft hair. She never really came alive for me. I can’t even remember her name.

The best Christmas dolls ever were my Old Cottage twins. Old Cottage dolls were very special. I’d mist up the special glass display case peeping at them in Hamleys. They were quite small but wondrously detailed: hand-made little dolls with soft felt skin, somehow wired inside so they could stand and stride and sit down. One Old Cottage doll in little jodhpurs and black leather boots could even leap up on her toy horse and gallop. The dolls were dressed in a variety of costumes. You could choose an old-fashioned crinoline doll, an Easter bonnet girl, even a fairy in a silver dress and wings. I preferred the Old Cottage girls in ordinary everyday clothes – gingham dresses with little white socks and felt shoes. Every doll had a slightly different face and they all had different hairstyles. Some were dark, some were fair; some had curls, but most had little plaits, carefully tied.

Biddy knew which I’d like best. She chose a blonde girl with plaits and a dark girl with plaits, one in a blue flowery dress, one in red checks. Then she handed them over to Ga. She must have been stitching in secret for weeks and weeks. When I opened my box on Christmas morning, it was a wondrous treasure chest. I unwrapped my Old

Cottage

twins and fell passionately in love with them at first sight. Then I opened a large wicker basket and discovered their

clothes

. Ga had made them little camel winter coats trimmed with fur, pink party dresses, soft little white nighties and tiny tartan dressing gowns, and a school uniform each – a navy blazer with an embroidered badge, a white shirt with a proper little tie, a pleated tunic, even two small felt school satchels.

I was in a daze of delight all Christmas Day. I could hardly bear to put my girls down so that I could eat up my turkey and Christmas pudding. I’d give anything to have those little dolls now with their lovingly stitched extensive wardrobe.

There’s a Christmas scene at the start and end of one of my books. Which do you think it is?

It’s

Clean Break

.

I was getting too big to believe in Santa but he still wanted to please me. I found a little orange journal with its own key; a tiny red heart soap; a purple gel pen; cherry bobbles for my hair; a tiny tin of violet sweets; a Jenna Williams bookmark; and a small pot of silver glitter nail varnish.

But Em thinks it’s going to be the best Christmas ever, especially when her stepdad gives her a real emerald ring – but it all goes horribly wrong. She has a tough time throughout the next year, but it’s Christmas Eve again in the last chapter. Someone comes knocking at the door and it looks as if this really

will

be a wonderful Christmas.

21

Books

WHENEVER I READ

writers’ autobiographies, I always love that early chapter when they write about their favourite children’s books. I was a total book-a-day girl, the most frequent borrower from Kingston Public Library. I think I spent half my childhood in the library. It meant so much to me to borrow books every week. It gives me such joy now to know that

I

’m currently the most borrowed author in British libraries.