Jacky Daydream (20 page)

Authors: Jacqueline Wilson

I picked up a lot of tips from

Ballet Shoes

but

most

of all I liked it for all the realistic little details of girl life. It was written in the 1930s so it was already dated when I read it twenty years later. I puzzled over the Fossil sisters’ poverty when they lived in a huge house on the Cromwell Road and had a cook and a nanny, but I loved it that they were such

real

girls. They quarrelled and larked around and worried about things. I felt they were

my

sisters. I sighed over Pauline becoming swollen-headed when she had her first big part in a play; I suffered agonies with Petrova, forced into acting when she felt such a fool on stage and longed to be with Mr Simpson fixing cars in his garage; I envied Posy as she glided through life, showing off and being insufferably cute. I knew how important it was for the girls to have a smart black velvet frock for their auditions. I loved the necklaces they got for a Christmas present from Great-uncle Matthew. I longed to go too on their seaside holiday to Pevensey. I knew without being told that it was definitely a cut above Clacton.

Noel Streatfeild was a prolific writer, and so I went backwards and forwards to the library, determined to read everything she’d ever written. I owned

Ballet Shoes

. It was one of the early Puffin books, with a bright green cover and Ruth Gervis’s pleasing pictures of the three girls in ballet dresses on the front. Those illustrations seemed so much part of the whole book (Ruth Gervis was Noel

Streatfeild’s

sister) that the modern un-illustrated versions all seem to have an important part lacking. But at least

Ballet Shoes

is still in print. Most of Noel Streatfeild’s books have long since disappeared from bookshops and libraries.

I loved

White Boots

and

Tennis Shoes

and

Curtain Up

. I was given

Wintle’s Wonders

as a summer holiday present. I remember clutching it to my chest so happily the edges poked me through my thin cotton dress. It was an agreeably chunky book, which meant it might last me several days.

Noel Streatfeild edited a very upmarket magazine for children called the

Elizabethan

, which I subscribed to. Enid Blyton had a magazine too,

Sunny Stories

, but that was very much for younger children. I had to struggle hard with some of the uplifting erudite articles in the

Elizabethan

, which was strange because Noel’s books were wonderfully easy to read.

She wrote some fascinating volumes of autobiography, and one biography of

her

favourite children’s writer, E. Nesbit.

I loved E. Nesbit too. Biddy gave me

The Story of the Treasure Seekers

when I was seven. It was my first classic but it wasn’t too difficult for me as it was written in the first person. You were meant to guess which one of the Bastable children was the narrator. It seemed pretty obvious to me that

it

was Oswald. I didn’t realize this was all part of the joke. Now I think

The Story of the Treasure Seekers

is a very warm and witty book, and it makes me crack up laughing, but as a seven-year-old I took it very seriously indeed. It seemed perfectly possible to me that the children

might

find a fortune. I failed to understand that Albert’s uncle frequently helped them out. I had no idea that if you added several spoonfuls of sugar to sherry, it would taste disgusting. I’d had a sip of Ga’s Harvey’s Bristol Cream at Christmas and thought it was even worse than Gongon’s black treacle medicine.

I

thought the taste would be improved with a liberal sprinkling of sugar too.

I wished there were more Bastable

girls

. I liked Alice a lot, and I felt sorry for poor po-faced Dora, especially when she wept and told Oswald she tried so hard to keep her brothers and sister in order because their dying mother had asked her to look after the family. There were occasional Edwardian references that I didn’t understand. I sniggered at the boys wearing garments called knickerbockers. But E. Nesbit’s writing style was so lively and child-friendly, and the children seemed so real that I felt I was a token Treasure Seeker too, especially as they lived in Lewisham.

I loved

The Railway Children

too, and was particularly fond of Bobbie. I liked it that Mother

was

a writer and whenever she sold a story, there were buns for tea. (I copied this idea many years later whenever

I

sold a story to a publisher!) There was a special children’s serial of

The Railway Children

on television – not the lovely film starring Jenny Agutter, this was many years earlier than that.

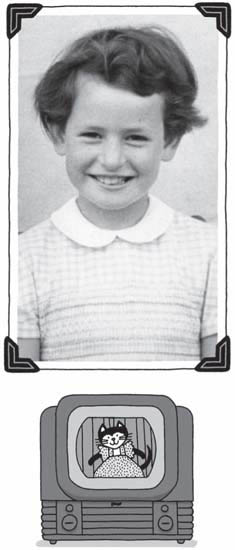

I sat in front of our new television set, spellbound. At the end of each episode the television announcer said a few words. She was called Jennifer, a smiley, wavy-haired girl who was only about twelve. She told all the child viewers about a

Railway Children

art competition.

‘All you have to do is illustrate your favourite scene,’ she said, smiling straight at me, cross-legged on the living-room floor in Cumberland House.

‘Mummy, can I do some painting?’ I said.

I had to ask permission because Biddy wasn’t keen on me having my painting water on the dining table and went through an elaborate performance of covering it over with newpapers, and rolling my sleeves right up to my elbows so my cuffs wouldn’t get smudged with wet watercolour.

‘Of course you’re not doing any painting now. You’re due for bed in ten minutes,’ said Biddy.

She believed in Early Nights, even though I’d often lie awake for hours.

‘But it’s for a competition on the television,’ I said. ‘

Please!

’

Biddy considered. I was quite good at painting for my age. Most of the children in the Infants were still at the big-blob combined-head-and-body stage, with stick arms and legs, the sky a blue stripe at the top of the page and the grass a green stripe at the bottom. I’d copied so many pictures out of my books that I had a slightly more sophisticated style, and I liked giving all my faces elaborate features. I was a dab hand at long eyelashes, though I was sometimes too enthusiastic, so my people looked as if two tarantulas had crawled onto each face.

‘Have a go then,’ said Biddy, relenting.

I was still having a go when Harry came home from work wanting his tea.

‘You’ll have to wait for once,’ said Biddy. ‘Jac’s painting.’

I dabbled my paintbrush and daubed proudly. I was on my third attempt. I’d tried hard to draw a train for my first picture, but I couldn’t work out what they looked like. I didn’t have any books with trains in them. I’d seen the little blue

Thomas The Tank Engine

books in W. H. Smith’s, but I didn’t fancy them as a girly read.

I made a determined attempt at a train, painting it emerald-green, but it looked like a giant caterpillar. I took another piece of paper and tried to draw the train head-on, but I couldn’t work out where the wheels went, and I’d used up so much

green

paint already there was just a dab left in my Reeves paintbox.

‘Blow the train,’ I muttered. I drew Bobbie and Phyllis and Peter instead, frantically waving red flannel petticoats. I drew them as if

I

was the train, rapidly approaching them. Their faces reflected this, their mouths crimson Os as they screamed.

I got a bit carried away with the high drama of it all, sloshing on the paint so vigorously that it started to run and I had to blot it up hurriedly with my cuddle hankie. The finished painting was a little wrinkly but I still felt it was quite good.

‘Put your name and address on the back carefully,’ said Biddy. ‘And put your age.’

I did as I was told and she sent it off to the television studio at Alexandra Palace the next day.

I won in my age category! It was the only time I won anything as a child. They didn’t send my painting back, which was a pity, but they sent a Rowney drawing pad as a prize. I’ve felt very fond of

The Railway Children

ever since.

I’d read my way through most of the girly children’s classics before I was ten. Woolworths used to stock garishly produced, badly printed children’s classics for 2s 6d, a third of the price of most modern books. I read

Little Women

over and over again, loving Jo, the tomboy harem-scarem sister who read voraciously and was desperate to

be

a writer. I also had a soft spot for Beth because she was shy and liked playing with dolls. I loved

What Katy Did

and felt desperately sorry for poor little Elsie, the middle child who wasn’t in on Katy and Clover’s secrets. I wasn’t so interested in Katy after she fell off the swing and endured her long illness. I couldn’t stomach saintly Cousin Helen. I enjoyed the Christmas chapter the most, and the detailed descriptions of all the presents.

I read

The Secret Garden

by Frances Hodgson Burnett, thrilled to read about irritable, spoiled children for a change, totally understanding

why

they behaved badly. I liked

A Little Princess

even more. I found Sara Crewe a magical character. I particularly loved the part at the beginning where she finds her doll Emily and there’s a detailed description of her trunk of clothes. I shivered in the attic with Sara after her fortune changed, and found the scenes with Becky and Ermengarde very touching. I was charmed that Sara made a pet out of Melchisedec – though if a real rat had scampered across the carpet in my bedroom, I’d have screamed my head off.

I read the beginning of

Jane Eyre

too. Biddy had a little red leatherette copy in the bookcase. I fingered my way through many of these books, but they were mostly dull choices for a child.

Jane Eyre

was in very small print, uncomfortable to

read

, but I found the first page so riveting I carried on and on. I was there with Jane on the window seat, staring out at the rain. I felt a thrill of recognition when she described poring over the illustrations in Bewick’s

History of British Birds

. I trembled when her cousins tormented her. I was horrified when Jane’s aunt had the servants haul her off to the terrifying Red Room. I shivered with Jane when she was sent to the freezing cold Lowood boarding school. I burned with humiliation when she was forced to stand in disgrace with the slate saying LIAR! around her neck. I wanted to be friends with clever odd Helen Burns too. I wanted to clasp her in my arms when she was sick and dying.

I read those first few chapters again and again – and Jane joined my increasingly large cast of imaginary friends.

Which girl in my books has Jane Eyre for

her

imaginary friend?

It’s Prue in

Love Lessons

.

For years and years I’d had a private pretend friend, an interesting and imaginative girl my own age called Jane. She started when I read the first few chapters of

Jane Eyre

. She stepped straight out of the pages and into my head. She no longer led her own Victorian life with her horrible aunt and cousins. She shared my life with my demented father.

Jane was better than a real sister. She wasn’t babyish and boring like Grace. We discussed books and pored over pictures and painted watercolours together, and we talked endlessly about everything.

I didn’t base the character of Prue on myself, even though we shared an imaginary friend

and

both had odd fathers. I was quite good at art, like Prue, and I was also fond of an interesting Polish art teacher at secondary school – but I

didn’t

fall in love with him!

24

Television and Radio

HOW MANY TELEVISION

channels can you watch on your set at home? How many channels do you think there were when I was a child? One! The dear old BBC – and in those days children’s television lasted one hour, from five to six. That was your lot.

I watched Muffin the Mule, a shaky little puppet who trotted across the top of a piano, strings very visible. He nodded and shook his head and did a camp little hoof-prance while his minder, Annette Mills, sang, ‘

We love Muffin, Muffin the Mule. Dear old Muffin, playing the fool. We love Muffin – everybody sing, WE LOVE MUFFIN THE MULE

.’