Jacky Daydream

Authors: Jacqueline Wilson

Contents

22. The Boys and Girls Exhibition

About the Book

Everybody knows Tracy Beaker, Jacqueline Wilson’s best-loved character. But what do they know about Jacqueline herself?

In this fascinating book, discover . . .

. . . how Jacky dealt with an unpredictable father, like Prue in

Love Lessons

.

. . . how she chose new toys in Hamleys, like Dolphin in

The Illustrated Mum

.

. . . how she sat entrance exams, like Ruby in

Double Act

.

But most of all discover how Jacky loved reading and writing stories. From the very first story she wrote, it was very clear that this little girl had a vivid imagination. But who would’ve guessed that she would grow up to be a bestselling, award-winning author!

Includes previously unseen photos, Jacqueline’s own school reports and a brand new chapter from Jacqueline on the response to the book, her teenage years and more!

For Emma, with all my love

1

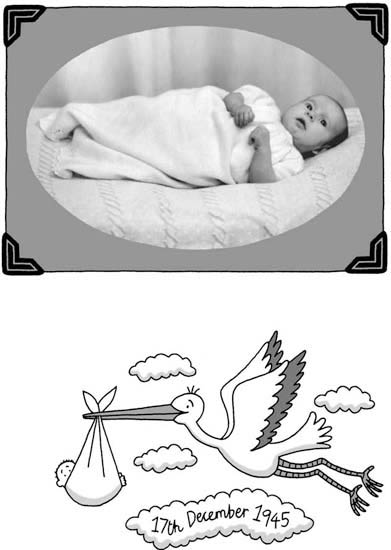

Birth!

I WAS MORE

than a fortnight late for my own birth. I was due at the beginning of December and I didn’t arrive until the seventeenth. I don’t know why. It isn’t at all like me. I’m always very speedy and I can’t stand being late for anything.

My mum did her level best to get me going. She drank castor oil and skipped vigorously every morning. She’s a small woman – five foot at most in her high heels. She was nearly as wide as she was long by this time. She must have looked like a beach ball. It’s a wonder they didn’t try to bounce the baby out.

When I eventually got started, I still took forty-eight hours to arrive. In fact they had to pull me out with forceps. They look like a medieval instrument of torture. It can’t have been much fun for my mother – or me. The edge of the forceps caught my mouth. When I was finally yanked out into the harsh white light of the delivery room in the hospital, my mouth was lopsided and partially paralysed.

They didn’t bother about mothers and babies bonding in those days. They didn’t give us time to

have

a cuddle or even take a good look at each other. I was bundled up tightly in a blanket and taken off to the nursery.

I stayed there for four days without a glimpse of my mother. The nurses came and changed my nappy and gave me a bath and tried to feed me with a bottle, though it hurt my sore mouth.

I wonder what I thought during those long lonely first days. I’m sure babies

do

think, even though they can’t actually say the words. What would I do now if I was lying all by myself, hungry and frightened? That’s easy. I’d make up a story to distract myself. So maybe I started pretending right from the day I was born.

I imagined my mother bending over my cot, lifting me up and cradling her cheek against my wispy curls. Each time a nurse held me against her starched white apron I’d shut my eyes tight and pretend

she

was my mother, soft and warm and protective. I’d hope she’d keep me in her arms for ever. But she’d pop me back in my cot and after three or four hours another nurse would come and I’d have to start the whole game all over again.

So perhaps I tried a different tack. Maybe I decided I didn’t need a mother. If I could only find the right spell, drink the necessary magic potion, my bendy baby legs would support me. I could haul

myself

out of the little metal cot, pack a bag with a spare nappy and a bottle, wrap myself up warm in my new hand-knitted matinée jacket and patter over the polished floor. I’d go out of the nursery, down the corridor, bump myself down the stairs on my padded bottom and out of the main entrance into the big wide world.

What was my mother thinking all this time? She was lying back in her bed, weepy and exhausted, wondering why they wouldn’t bring her baby.

‘She can’t feed yet, dear. She’s got a poorly mouth,’ said the nurses.

My mum imagined an enormous scary wound, a great gap in my face.

‘I thought I’d given birth to a monster,’ my mum told me later. ‘I wasn’t sure I

wanted

to see you.’

But then, on the fourth day after my birth, one of the doctors discovered her weeping. He told her the monster fears were nonsense.

‘I’ll go and get your baby myself,’ he said.

He went to the nursery, scooped me out of my cot and took me to my mother. She peered at me anxiously. My mouth was back in place, just a little sore at the edge. My eyes were still baby blue and wide open because I wanted to take a good look at my mother now I had the chance. I wasn’t tomato red and damp like a newborn baby. I was now pink-and-white and powdered and my hair was fluffy.

‘She’s pretty!’ said my mum. ‘She’s just like a little doll.’

My mum had always loved dolls as a little girl. She’d played with them right up until secondary school. She loved dressing them and undressing them and getting them to sit up straight. But I was soft flesh, not hard china. My mother cradled me close.

My dad came and visited us in hospital. Fathers didn’t get involved much with babies in those days but he held me gently in his big broad hands and gave me a kiss.

My grandma caught the train from Kingston up to London, and then she got on a tube, and then she took the Paddington train to Bath, where we lived, and then a bus to the hospital, just to catch a glimpse of her new granddaughter. It must have taken her practically all day to get there because transport was slow and erratic just after the war.

She was a trained milliner, very nifty with a needle, quick at knitting, clever at crochet. She came with an enormous bag of handmade baby clothes, all white, with little embroidered rosebuds, a very special Christmas present when there was strict clothes rationing and you couldn’t find baby clothes for love nor money.

I had my first Christmas in hospital, with pastel-coloured paperchains drooping round the ward and

a

little troop of nurses with lanterns singing carols and a slice of chicken and a mince pie for all the patients. This was considered a feast as food was still rationed too. Luckily my milk was free and I could feed at last.

Can you think of a Jacqueline Wilson book where the main character has a little chat even though she’s a newborn baby?

It’s Gemma, in my book

Best Friends

. Gemma chats a great deal, especially to Alice. They’ve been best friends ever since the day they were born. Gemma is born first, at six o’clock in the morning, and then Alice is born that afternoon. They’re tucked up next to each other that night in little cots.

I expect Alice was a bit frightened. She’d have cried. She’s actually still a bit of a crybaby now but I try not to tease her about it. I always do my best to comfort her.

I bet that first day I called to her in baby-coo language. I’d say, ‘Hi, I’m Gemma. Being born is a bit weird, isn’t it? Are you OK?’

I often write about sad and worrying things in my books, like divorce and death – though I try hard to be as reassuring as possible, and I always like to have funny parts. I want you to laugh as well as cry. One of the saddest things that can happen to you when you’re a child is losing your best friend, and yet even the kindest of adults don’t always take this seriously.

‘Never mind, you’ll quickly make a

new

best friend,’ they say.

They don’t have a clue how lonely it can be at school without a best friend and how you can ache with sadness for many months. In

Best Friends

I tried hard to show what it’s really like – but because Gemma is pretty outrageous it’s also one of my funniest books too. I like Gemma and Alice a lot, but I’m particularly fond of Biscuits.

He’s my all-time favourite boy character. He’s so kind and gentle and full of fun, and he manages not to take life too seriously. Of course he eats too much, but I don’t think this is such an enormous sin. Biscuits will get tuned in to healthy eating when he’s a teenager, but meanwhile I’m glad he enjoys his food. His cakes look delicious!