Jacky Daydream (6 page)

Authors: Jacqueline Wilson

I was a reasonably well-behaved child, though as my mum said, I had my moments. If I was

naughty

, I was sent upstairs to bed. If I was being really irritating, I got smacked too. Parents smacked their children without any guilt or remorse in those days. It was a perfectly acceptable thing to do. I never got really

hurt

. My mum just gave me a slap on the back of my legs or on my bottom. My grandma gave me a light tap if she caught me with a finger in a pot of her delicious home-made raspberry jam, or picking holes where her kitchen plaster was peeling. My grandpa didn’t get involved enough to smack. I asked Biddy if Harry ever smacked me. I was frequently frightened of him, right up to the day he died in his fifties, but I couldn’t remember him hitting me.

‘He hit you once when you were little, and it worked a treat,’ said Biddy. ‘You were standing up in your cot one evening, howling and howling, and you simply wouldn’t be quiet. I went up to try to get you to lie down and go to sleep. So did Ga. You simply wouldn’t see reason. So Harry went up and he gave you an almighty whack and you shut up straight away.’

If I’d done something really bad, I tried to talk myself out of being blamed. I didn’t exactly fib. I simply told stories.

‘

I

didn’t do it,’ I’d say, wide-eyed, shaking my head. ‘Gwennie did it.’

I’d sigh and shake my head and apologize for

Gwennie’s

behaviour. Gwennie was one of the imaginary friends who kept me company during the day. Biddy and Ga found this mildly amusing at first but the novelty soon wore off, and I found myself being punished twice over for Gwennie’s misdemeanours.

‘You must always always always tell the truth, Jac,’ Biddy said solemnly. ‘You mustn’t

ever

tell fibs.’

Try telling that to a storyteller!

Which girl in one of my books always

tries

to tell the truth? She lives with her grandparents, just like I did when I was little

.

It’s Verity in

The Cat Mummy

.

I try very hard to tell the truth. That’s what my name Verity means. You look it up. It’s Latin for truth.

I can be as naughty as the next person but I try not to tell lies. However . . . it was getting harder and harder with this Mabel-mummy situation.

The Cat Mummy

is a very sad book (though there are lots of funny bits too). Many children write to me to tell me about their pets. They’re very special to them. They say: ‘Dear Jacqueline, I’m nine years old and I love reading your books and I’ve got a cat called Tiger and a guinea pig

called

Dandelion. Tiger is stripy and Dandelion loves

eating

dandelions. Oh, and I’ve got a mum and a dad. I’ve got a little brother too and he is a

pest

.’

They nearly always mention their pets

before

their parents and brothers and sisters, as if they’re much more important. The sad thing is, pets don’t live as long as people. I often get the most touching tear-stained letters, telling me that some beloved hamster or white rat has died.

I decided to write a story about a girl whose old cat dies. She feels terrible and wishes she could preserve her in some way. She’s just learned about the Ancient Egyptians at school and it gives her a very very weird idea!

8

Shopping

I LOVED LIVING

as an extended family at Fassett Road. I liked all the little routines of my preschool life. We would walk into Kingston every day to go shopping. It was a fifteen-minute brisk trot, a twenty-five-minute stroll. Biddy stuck me in my pushchair to save time. It was a pleasant walk, across a little blue bridge over the Hog’s Mill stream, down a long quiet street of Victorian houses, some large, some small, past the big green Fairfield, past the library, until we could see the red brick of the Empire Theatre in the middle of town. (I was taken to see

Babes in the Wood

there when I was little and loved it, though I found it puzzling that the boy Babe was a girl and the Old Dame clearly a man.)

Ga had already developed arthritis and could only walk slowly, so we strolled together, peering at everything along the way. We had our favourite houses. She would always pause in front of a pretty double-fronted house with four blossom trees in the garden. ‘

That

’s my favourite,’ she’d say, so of course it was my favourite too.

I live in that house now. My grandma is long dead, but I’ve hung her photo on the wall – and a replacement china Mabel sits underneath.

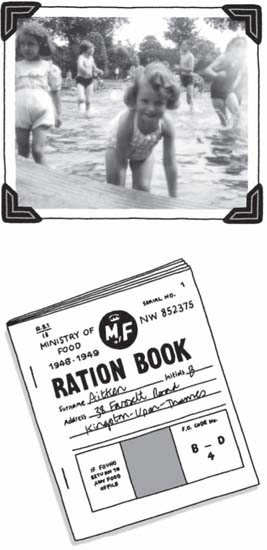

Shopping was very different in those days. I loved going to Sainsbury’s, but it wasn’t a big supermarket with aisles and open shelves and trolleys. The Kingston Sainsbury’s then had beautiful mosaic-tiled walls like an oriental boudoir. You queued at the butter counter and watched some white-overalled wizard take the butter and pat it into place with big wooden paddles. You couldn’t afford very much butter so you always had margarine too. They were both so hard you had to butter the end of the loaf and then slice it. There wasn’t any such thing as ready-sliced bread in packets then.

Then you queued at the cheese counter until another white-garbed lady sliced off the exact amount of cheese for you with a wire and ticked your ration book. You queued at the bacon counter and watched the bacon boy (who always wore a pencil behind his ear) use the scary bacon slicer, cutting your four rashers of best back bacon into wavy ribbons on greaseproof paper. You could queue for a whole

hour

in Sainsbury’s and still come out with precious little in your string shopping bag.

Then we’d go to John Quality’s on the corner by the market. It was another grocer’s, with big sacks

of

sugar and nuts and dried fruit spread out on the floor, just the right height for me. I was always a very good girl, but Gwennie sometimes darted her hand into a sack and pulled out a dried plum, just like Little Jack Horner in the nursery-rhyme book at home.

Then we’d trail round the market, maybe queuing for plaice or cod or yellow smoked haddock from the fish stall on a Friday, spending a long time haggling at the fruit stall and the veg stall. You could get bananas and oranges now the war was over, but everything was strictly seasonal and none of us had ever even

heard

of exotic things like kiwi fruit or avocado pears or butternut squash. Fruit meant apples and pears, veg meant cabbage and carrots and cauliflower. The frozen pea hadn’t even been invented. We didn’t have a fridge or freezer anyway.

The only shop I disliked was the butcher’s – it smelled of blood. The meat wasn’t cut up in neat cellophaned packets, it was festooned all over the place, great red animal corpses hung on hooks in the wall, chickens still in their feathers, rabbits strung in pairs like stiff fur stoles, their little eyes desperately sad.

I shut my own eyes. I breathed shallowly, trying hard not to moan and make a fuss, because if I’d behaved perfectly, I

might

be taken to Woolworths for a treat. I loved Woolworths. It had its own

distinctive

smell of sweets and biscuits and scent and floor polish. (When I left home and went to live in Scotland at seventeen, I used to go into the Dundee Woolworths just to breathe in that familiar smell.)

I liked the toy counter best. I’d circle it on tiptoe, trying to see all the penny delights: the glass marbles, the shiny red and blue and green notebooks, the spinning tops, the tin whistles, the skipping ropes with striped handles. I always knew what I wanted most. Woolworths sold tiny dolls, though sadly not the beautiful little china dolls of my grandma’s childhood. These were moulded pink plastic – little girls with pink plastic hair and pink plastic dresses, little boys with pink plastic shirts and pink plastic trousers, and lots and lots of pink plastic babies in pink plastic pants. The babies came in different sizes. You could get big penny babies alarmingly larger than their halfpenny brothers and sisters.

I was a deeply sexist small girl. I spurned all the pink plastic boys. I bought the girls and the little babies, playing with them for hours when I got home. I sometimes made them a makeshift home of their own in a shoebox. I took them for trips to the seaside in my sandpit. Best of all, I stood on a stool at the kitchen sink and set them swimming in the washing-up basin. They dived off the taps and went boating in a plastic cup and floated with

their

little plastic toes in the air.

I was very fond of the water myself. I hadn’t yet been swimming in a proper pool but we’d had several day trips to Broadstairs and Bognor and Brighton when I’d had a little paddle. Most days in the summer Ga took me for a ten-minute walk to Claremont Gardens, near Surbiton Station, where there was a paddling pool. She stripped me down to my knickers and I ran into the pool and waded happily in and out and round about.

I wasn’t supposed to go right under and get my knickers wet, but even if I was careful, the other children often splashed and I got soaked. One time Ga thought my knickers were so sopping wet I’d be better off without them, so she pulled my dress on, whipped my knickers off, and walked home with them clutched in a soggy parcel in her hand. We encountered Mrs Wilton, her next-door neighbour, on the way home.

‘Look at this saucepot!’ said Ga, twitching up my dress to show my bare bottom.

Then she waved my wet knickers in the air while she and Mrs Wilton laughed their heads off. I was mortified. I was worried Mrs Wilton might think I’d

wet

my knickers and then she’d tell her children, Lesley and Martin, and they’d think me a terrible baby.

I liked the trips to the paddling pool, but the

best

treat of all was a walk to Peggy Brown’s cake shop in Surbiton. There’s a health food shop on the site now, but in the long-ago days of my childhood the only health supplements we had were my free orange juice for vitamin C (delicious) and cod liver oil for vitamins A and D (disgusting) and some black malty treacle in a jar that my grandpa licked off a spoon every day.

Our concept of eating for health was a little skewed too: a fried-egg-and-bacon breakfast was considered the only decent way to start the day so long as you were lucky enough to have the right number of coupons; white bread and dripping was a nutritious savoury snack; coffee was made with boiled full-cream milk and a dash of Camp; and as long as you ate your bread and butter first then you always tucked into a cake at tea time.

Ga made proper cooked meals every day. She rolled her own pastry and made wonderful jam with the berries from the back garden, but I can’t remember her baking cakes. On ordinary days we had pink and yellow Battenburg cake or sugary bath buns from the baker’s near Kingston market – but once a week we went to Peggy Brown’s special cake shop.

They were fancy cakes with marzipan and butter cream and little slithers of glacé cherry or green angelica. They had exotic names: Jap cakes,

coconut

kisses, butterfly wings. There were tarts with three different jams – raspberry, apricot and greengage, like traffic lights. My favourites were little individual lemon tarts with a twirl of meringue on top.

Excellent as they were, the cakes were only incidental. We went to Peggy Brown’s to look at the shop windows. The owner had a vast collection of dolls, from large Victorian china dolls as big as a real child down to tiny plastic dolls not very different from my Woolworths girls.

Each season Peggy Brown did a magnificent display: false snow and a tiny Christmas tree in winter; Easter eggs and fluffy bunnies in the spring; real sand and a painted blue sea in summer; red and gold leaves and little squirrels in autumn. Each season every single doll had a new outfit. They had hoods and mufflers and velvet coats, Easter bonnets and party frocks, swimming costumes and tiny buckets and spades, Fair Isle jumpers with matching berets and miniature wellington boots.

Ga and I gazed and gazed. Ga worked out how Peggy Brown had designed the costume, cut the pattern, sewn the seams. I rose up, strode straight through the glass and squatted amongst the dolls. We made a snowman or stroked the rabbits or paddled in the sea or kicked the crackly autumn

leaves

until Ga gave me a little tug. I’d back out of the glass into the real world and we’d go home and eat our Peggy Brown cakes for tea.