Jacky Daydream (4 page)

Authors: Jacqueline Wilson

The dog barked furiously and then leaped at my pram. I screamed. Biddy and my grandma came running but they were too late. The dog seized hold of Timmy and ran off with him, shaking and savaging him as if he was a huge rat. He dropped him halfway down the street, tiring of the game. Timmy was brought back scalped, his face chewed to pulp and both arms severed. I wanted to keep and tend him and love him more than ever, but Biddy and Ga said I couldn’t possibly play with him now. Poor Timmy was thrown in the dustbin.

I kept my children cooped up indoors for a long time after that. I rode my little green trike in the garden but tensed anxiously whenever I heard the Maloneys’ dog barking. But it didn’t put me off dogs in general. I longed for a puppy but Ga wasn’t any fonder of animals than my mother.

I would always pat any friendly dog I found and

make

up imaginary dogs when I played Mothers and Fathers. When I read the Famous Five books at six or seven, I didn’t envy George her adventures or even her famous picnics with lashings of ginger beer. I just longed for her dog Timmy. Then one day out at the seaside we came across a very lifelike toy Pekinese in a department store. It was a model of the artist Alfred Munnings’s dog Black Knight, VIP. I was told this stood for Very Important Person, which seemed an excessive title for a dog, but I wasn’t quibbling. I

longed

for this wonderful toy dog but it was hopelessly expensive. Astonishingly, Biddy fumbled in her white summer handbag for her purse. She bought him!

‘Is he for

me

?’ I whispered.

‘Well, who else would it be for, you soppy ha’p’orth,’ said Biddy.

‘Is he going to be my birthday present or Christmas present?’

‘You might as well have him now,’ said Biddy.

‘Oh, Mummy, really! You’re the best mum in the whole world!’

‘Yes, of course I am,’ said Biddy, laughing. ‘Now, let’s hope you stop going on and on about getting a wretched dog. You’ve got one now!’

I walked out of the shop with him under my arm. He stayed permanently tucked there for weeks. Old ladies stopped me in the street and

asked

to pat my dog and acted surprised when they found out he wasn’t real. I told them shyly that his name was Vip.

At last I was able to write school essays about My Pet. Vip slept in my arms every night. Even when I was a teenager, he slept at the end of my bed by my feet, like one of those little marble dogs on a tomb. I still have him, though my mum had a go at restuffing him and he’s never been the same since – he’s very fat and lumpy now. Even his sweet expression has changed so that now he looks both dopey and bad-tempered. He obviously didn’t take kindly to being restuffed.

I still don’t have a real dog because I travel about too much, but when I slow down and stay put, I intend to have not one dog, but two – a retired greyhound called Lola and a little black miniature poodle called Rose.

Which of my characters had a doll called Bluebell – and a fantasy Rottweiler for a pretend pet?

It was Tracy Beaker, of course.

My mum came to see me and she’d bought this doll, a doll almost as big as me, with long golden curls and a bright blue lacy dress to match her big blue eyes. I’d never liked dolls all that much but I thought this one was wonderful. I called her Bluebell and I undressed her right down to her frilly white knickers and dressed her up again and brushed her blonde curls and made her blink her big blue eyes, and at night she’d lie in my bed and we’d have these cosy little chats and she’d tell me that Mum was coming back really soon, probably tomorrow.

Poor Tracy. Someone pokes Bluebell’s eyes out and she never feels the same about her afterwards.

I think it’s just as well Tracy doesn’t

really

have a Rottweiler.

Tracy Beaker is the most popular character I’ve ever invented. She’d be so thrilled to know she’s

had

a very popular television series, her own magazine, all sorts of Totally Tracy toys and stationery and T-shirts and pyjamas, a touring musical and now

three

books about her,

The Story of Tracy Beaker, The Dare Game

and

Starring Tracy Beaker

.

I’ve often told the silly story of how I got her name. I was lying in my bath one morning, starting to make up Tracy’s story in my head as I soaped myself. I knew I wanted my fierce little girl to be called Tracy. It sounded modern and bouncy and had a bit of attitude. I couldn’t find a suitable surname to go with it. Everything sounded silly or awkward. I looked around the bathroom for inspiration. Tracy Flannel? Tracy Soap? Tracy Toothbrush? Tracy Tap? Tracy

Toilet

?

I gave up and got on with washing my hair. I don’t have a shower, so I just sluice the shampoo off with an old plastic beaker I keep on the edge of the bath. I picked up the beaker. Aha!

Tracy Beaker!

6

Hilda Ellen

I HAD TWO

books when I was at Fassett Road. I had my birthday-present history book and now I also had a Margaret Tarrant nursery rhyme book with rather dark colour plates. The children wore bonnets and knickerbockers and boots and fell down hills and got chased by spiders and were whipped soundly and sent to bed. My mum or my dad or my grandma must have read them to me several times because I knew each nursery rhyme by heart.

I can’t imagine my grandad reading to me. He was a perfectly sweet, kindly man, though his bushy eyebrows and toothbrush moustache made him look fierce. He put on a pinstripe suit every weekday, with a waistcoat and a gold watch on a fob chain, kept in its own neat pocket, and caught the train from Surbiton. He spent all day at ‘business’ in London. He was a carpet salesman in Hamptons, a big department store. He was eventually made manager of his department, a very proud day. He always smelled slightly of carpets, as if he secretly rolled himself up in his stock.

He returned home at half past six, listened to

The Archers

on the radio, ate his supper and fell asleep in the armchair, pale hands folded over his waistcoat as if guarding his watch. He gave me a sixpence occasionally or offered me a boiled sweet but that was the extent of our relationship. I don’t think I ever sat on his lap. I remember once combing his hair playing hairdressers when I was older, but this was unsatisfactory too, as he had very little hair to comb.

He seemed to have very little of anything, including personality, a nine-to-five man who did nothing with his life – yet he had fought in the reeking muddy trenches in the First World War until he was shot and sent home, badly wounded. Maybe he was happy to embrace a totally peaceful, boring, suburban life – no mud, no bullets, no swearing soldiers, just his little hedge-trimmed semi and his wife, and Phil and Grace Archer and old Walter Gabriel on the radio.

My grandma seemed settled too, perhaps because she’d had such a rackety-packety childhood. I loved curling up by her chair as she sewed, getting her to tell me stories about when-she-was-a-little-girl. These weren’t silly Diddle-Diddle-Dumpling See-Saw-Marjorie-Daw stories that didn’t make sense, like the rhymes in the Margaret Tarrant book. These were gritty

tales

of an unwanted, unloved child sent from pillar to post – the sort of stories I’d write myself many years later.

My grandma’s mother died of cancer when she was only twenty-seven. Ga, Hilda Ellen, was seven, and her brother Leslie was five. Her father, Papa, was a Jack-the-lad businessman, a fierce, feisty little man up to all sorts of schemes. He palmed his children off on different relatives and got on with his life without them. Leslie was packed off to an uncle, and as far as I know, was never reunited with his sister.

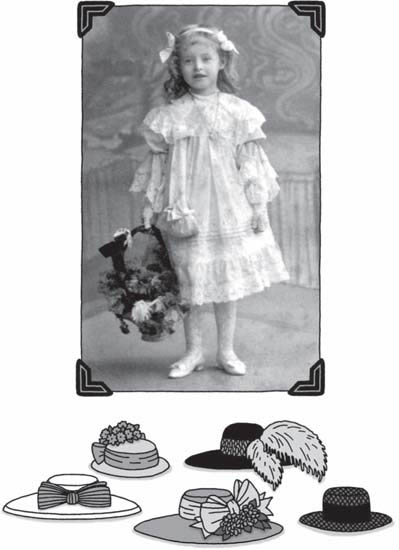

Hilda Ellen was sent to two maiden aunts who were very strict, but they taught her to sew beautifully. She loved dolls. She didn’t have a proper big china doll – no one wanted to waste any money on giving her presents – but she scavenged for coppers and sometimes dared save her Sunday school donation, and bought tiny china dolls from the local toyshop. You could get one the size of your thumb for a halfpenny but her hair was only painted in a blob on her head. Penny dolls were the size of your finger and had real silky long hair you could arrange with a miniature brush.

All the dolls were stark naked apart from painted socks and shoes. Hilda Ellen raided her aunts’ workbox and made them tiny clothes. At

first

they were just hastily stitched wrap-around dresses and cloaks, but soon she had the skill to make each doll a set of underwear, even ruffled drawers, and over these they wore embroidered dresses and pinafores and coats with hoods to keep their weeny china ears warm.

The dolls were a demanding bunch and wished for more and more outfits. Hilda Ellen got bolder in her search for material. When the dolls wanted to go to a ball, she crawled to the back of the older auntie’s wardrobe and cut a great square out of the back of an old blue silk evening frock. The auntie caught Hilda Ellen twirling her dolls down the staircase, looking like a dancing troupe in their blue silk finery. She recognized the material. She wouldn’t have worn that evening frock in a month of Sundays but she was still appalled. Hilda Ellen was sent packing.

Papa had taken up with a new lady by this time and didn’t want a daughter getting in the way. Hilda Ellen was sent to relatives who ran a pub in Portsmouth. It was a rough pub, always heaving with sailors, not really a suitable home for a delicate little girl, but Hilda Ellen loved it there.

‘I didn’t have to stay in my room. Well, I didn’t

have

a room. I just had a cot and shared with the bar girls. But every evening I helped in the pub, collecting up the glasses. My uncle would often sit

me

on the counter and get me to sing a song for all the sailors.’

She was given so many pennies she had a whole drawerful of tiny dolls, and she bought her own scraps of silk and velvet and brocade from the remnant stall at the Saturday market.

Then she was given her own big doll! The hairdressing salon along the road had a china doll in the window with very long golden curls of real hair. She sat there to advertise the hairdressing expertise of Mr Bryan, the owner. Hilda Ellen snipped her own hair every now and then, but she often paused outside the salon window, gazing at the beautiful china doll in her cream silk dress, her golden curls hanging right down to her jointed hips.