Jacky Daydream (3 page)

Authors: Jacqueline Wilson

4

Housewife’s Choice

BIDDY DIDN’T JUST

keep me sparkling clean. She fussed around our rented flat every day after breakfast, dusting and polishing and carpet-sweeping. She didn’t wear a turban and pinny like most women doing dusty work. She thought they looked common.

She listened to the Light Programme on the big wooden radio, tuning in to

Housewife’s Choice

, singing along to its signature tune,

doobi-do do doobi-do

, though she couldn’t sing any song in tune, not even ‘Happy Birthday’.

When she was done dusting, we went off to the shops together. You couldn’t do a weekly shop in those days. We didn’t have a fridge and there was so little food in the shops, you couldn’t stock up. You had to queue everywhere, and smile and simper at the butcher, hoping he might sell you an extra kidney or a rabbit for a stew. Biddy was pert and pretty so she often got a few treats. One day, when he had no lamb chops, no neck or shoulder, he offered my mum a sheep’s head.

She went home with it wrapped in newspaper,

precariously

balanced on the pale green covers of my pram. She cleaned the head as best she could, holding it at arm’s length, then shoved it in the biggest saucepan she could find. She boiled it and boiled it and boiled it, then fished it out, hacked at it and served it up to Harry with a flourish when he came back from work.

He looked at the chunks of strange stuff on his plate and asked what it was. She was silly enough to tell him. He wouldn’t eat a mouthful. I was very glad I still had milk for my meals.

She couldn’t go back to the butcher’s for a few days as she’d had more than her fair share of meat, so she tried cutting the head up small and swooshing it around with potatoes and carrots, turning it into sheep soup.

Harry wasn’t fooled. There was a big row. He shouted that he wasn’t ever going to eat that sort of muck. She screamed that she was doing her best – what did he expect her to do, conjure up a joint of beef out of thin air? He sulked. She wept. I curled up in my cot and sucked my thumb.

There were a lot of days like that. But in the first photos in the big black album we are smiling smiling smiling, playing Happy Families. There are snapshots of days out on the tandem, blurred pictures of me squinting in the sunlight but still smiling. I’m in my summer woollies now, still

wearing

several layers, but at least my legs are bare so I can kick on my rug.

There are professional photos of me lying on my tummy, stripped down to my knitted knickers, smiling obediently while Biddy and the photographer clapped and cavorted. There are pictures of me sitting up on the grass but I always have a little rug under me to keep me clean. There’s even a photo of me in my tiny tin bath. What a palaver it must have been to fill it up every day and then lug it to the lavatory to empty it.

My grandma must have been stitching away as I’m always wearing natty new outfits. By the autumn I’m wearing a tailored coat with a silky lining, a neat little hood and matching buttoned leggings, with small strappy shoes even though I can’t walk properly yet.

I had my first birthday. Biddy and Harry gave me a book – not a baby’s board book, a proper child’s history book, though it had lots of pictures. Biddy wrote in her elaborately neat handwriting:

To our darling little Jacqueline on her first birthday, Love from Mummy and Daddy

.

I don’t think I ever

read

my first book, but when I was older, I liked to look at the pictures, especially the ones of Joan of Arc and the little Princes in the Tower. I think my grandma might have made me felt toy animals because there’s a photo of me

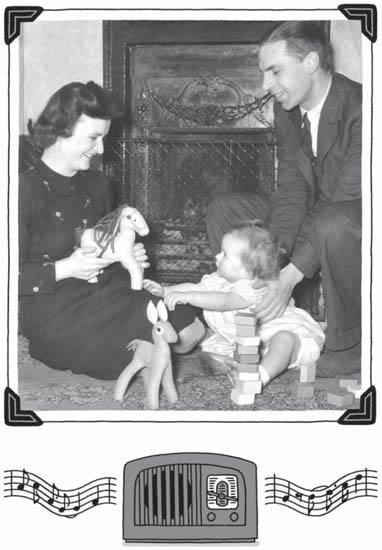

sitting

on the rug between Biddy and Harry, playing with a horse with a felt mane and a bug-eyed fawn.

The local paper did a feature on young married couples living in Bath and Biddy and Harry were picked for it. She’s wearing a pretty wool dress embroidered with daisies and thick lisle stockings. Harry is wearing a smart suit with a waistcoat, probably his year-old wedding suit, but he’s got incongruous old-man plaid slippers on his feet. Did he have to change his shoes the minute he got inside the front door in case he brought mud in?

We look a happy little threesome, sitting relaxed in front of the fire. We

needed

that fire during the winter of 1946/1947. It was so cold that all the pipes froze everywhere. The outside lavatory froze up completely. There was no water, not even cold. Harry had to go up the road with a bucket and wait shivering at the standpipe. Biddy stuck it out for a few weeks, but then she packed a big suitcase for her, a little one for me, dismantled my cot, balanced the lot on my pram, and took us to stay with my grandparents in Kingston.

We stayed on, even when it was spring. Harry lived by himself in Bath until the summer, and then left the Admiralty and managed to get a job in the Civil Service in London, even though he’d left school at fourteen. They looked for a place to rent but half of London had been bombed. There were

no

flats anywhere, so Harry moved in with my grandparents too.

Which of my books starts with the main girl describing all the beds she’s ever slept in, including her baby cot? For a little while they live with her step-gran, though it’s a terrible squash – and my poor girl has to share a bed with this grandma

.

It’s

The Bed and Breakfast Star

.

I had to share it with her. There wasn’t room in her bedroom for my campbed, you see, and she said she wasn’t having it cluttering up her lounge. She liked it when I stopped cluttering up the place too. She was always wanting to whisk me away to bed early. I was generally still awake when she came in. I used to peep when she took her corset off.

She wasn’t so little when those corsets were off. She took up a lot of the bed once she was in it. Sometimes I’d end up clutching the edge, hanging on for dear life. And another thing. She snored.

I love Elsa in

The Bed and Breakfast Star

. She’s so kind and cheery, though she does tell really awful old jokes that make you groan! I’m not very good at making up jokes myself, so when I was writing the book, I asked all the children I met in schools and libraries if they knew any good jokes, and then I wrote them down in a little notebook, storing them up for Elsa to use. There were a lot of very

funny

jokes that were unfortunately far too rude to print in a book!

There used to be several bed and breakfast hotels for the homeless in the road where I lived. I used to chat to some of the children in the sweetshop or the video shop. I knew how awful it must be to live in cramped conditions in a hotel, and many of their mums were very depressed. Still, the children themselves seemed lively and full of fun. I decided to write a book about what it’s like to be homeless, but from a child’s point of view.

The Bed and Breakfast Star

has a happy ending, with Elsa and her family living in the very posh luxury Star Hotel – though I don’t know how long they’ll be able to stay there!

5

38 Fassett Road

WE LIVED AT

38 Fassett Road, Kingston, for the next two years. I was probably the only one of us who liked this arrangement. It was much more peaceful living with Ga and Gongon. These were the silly names I called my grandparents before I could talk clearly and I’m afraid they stuck.

It must have been difficult for my grandparents having a volatile couple and a toddler sharing their living room, cluttering up their kitchen, using the only bathroom and lavatory. It must have been agony for my parents not being able to row and make up in private. They couldn’t even be alone together in their own bedroom because I was crammed in there with them in my dropside cot.

I didn’t have my own bedroom until I was six years old. I didn’t really

need

one when I was little. I didn’t have many possessions. I had my cot. I had one drawerful of underwear and jumpers in my mother’s chest of drawers. I had one end of her wardrobe for my frocks and pleated skirts and winter coats.

I had my toys too, of course, but there weren’t

many

of them. It was just after the war and no one had any money. I did royally compared with most little girls. My first doll was bigger than me, hand-made by my Uncle Roy. He was in hospital a long time during the war because his whole jaw was shot away and had to be reconstructed. He passed the time doing occupational therapy, making a huge doll for me, and then later one for

his

newly born daughter Rosemary.

I called my doll Mary Jane. She had an alarmingly nid-noddy head and her arms and legs dangled depressingly but I tried hard to love her. She had brown wool curls, a red felt jacket and a green skirt. You could take her clothes off but then she looked like a giant string of sausages so I generally kept them on. Mary Jane never developed much personality, but I remember being astonished on a rare visit to my uncle and aunt’s to find that Rosemary’s twin doll had exactly the same staring face and woolly hair and dangling body but wore a yellow jacket and a blue skirt. It was as if I’d found a letter box painted yellow, a lamppost painted blue. She was my first doll, my only doll, and I thought all other rag dolls would be identical.

I was given a new doll the next Christmas. I had a doll every single Christmas throughout my childhood – and a book for my birthday. My next doll was Barbara. She was a real shop-bought doll

with

a cold hard body and eyes that opened and shut if you tipped her upside down. The first day I owned her I tipped her backwards and forwards until she must have been dizzy, and her eyelids went

click click click

like a little clock. Her eyes were brown and her hair was short and brown and curly, rather like mine. She had a frock with matching knickers and little silky white socks and white plastic shoes that did up with a small plastic bobble.

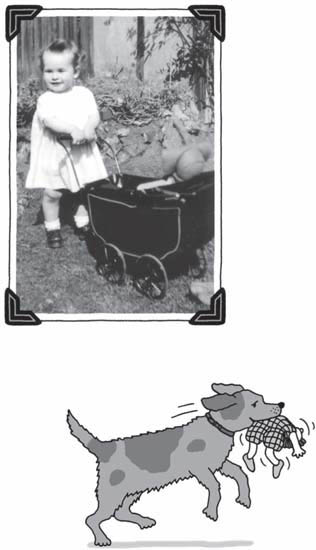

She was a little girl doll, not a baby, but she had her very own pram. Her composition legs were permanently bent in a spread sitting position so she was very happy to be wheeled about. I pushed the pram around my grandma’s back garden and up and down the hallway and in and out of her kitchen.

I had twins the following year, Timmy and Theresa, soft dolls with green checked clothes. Timmy had rompers and Theresa a little dress, again with matching knickers. They had little felt shoes, very soft. The twins were soft all over, but compact – very satisfying after large floppy Mary Jane and hard Barbara, though I tried hard to love all my children equally. Some great-auntie gave me Pandora, a quirky little rag doll with a severe hat and waistcoat and a disconcertingly middle-aged face. My pram was getting crowded by this time.

It

was hard to cram all five dolls under the covers.

Then tragedy struck. I was pottering with my pram in the front garden, wheeling my family round and round the pretty crocus patch, when the Maloneys’ mad dog came bounding in the front gate. The Maloneys were a very large Irish family, all with carrot-coloured hair and a zest for living. They’d been bombed out and temporarily rehoused opposite my grandparents, causing havoc in the quiet suburban street.