Jacky Daydream (2 page)

Authors: Jacqueline Wilson

2

My Mum and Dad

I WAS FINE

. My mum was fine. We could go home now.

We didn’t really have a

proper

home, a whole house we owned ourselves. My mum and dad had been sent to Bath during the war to work in the Admiralty. He was a draughtsman working on submarine design, she was a clerical officer. They met at a dance in the Pump Room, which sounds like part of a ship but is just a select set of rooms in the middle of the city where they had a weekly dance in wartime.

My mum and dad danced. My mum, Biddy, was twenty-one. My dad, Harry, was twenty-three. They went to the cinema and saw

Now, Voyager

on their first proper date. Biddy thought the hero very dashing and romantic when he lit two cigarettes in his mouth and then handed one to his girl. Harry didn’t smoke and he wasn’t one for romantic gestures either.

However, they started going out together. They went to the Admiralty club. They must have spun out a lemonade or two all evening because neither of them drank alcohol. I only ever saw them down

a

small glass of Harvey’s Bristol Cream sherry at Christmas. They went for walks along the canal together. Then Harry proposed and Biddy said yes.

I don’t think it was ever a really grand passionate true love.

‘It wasn’t as if you had much choice,’ Biddy told me much later. ‘There weren’t many men around, they were all away fighting. I’d got to twenty-one, and in those days you were starting to feel as if you were on the shelf if you weren’t married by then. So I decided your father would do.’

‘But what did you like about Harry?’

My mum had to think hard. ‘He had a good sense of humour,’ she said eventually.

I suppose they did have a laugh together. Once or twice.

Harry bought Biddy an emerald and diamond ring. They were very small stones, one emerald and two diamonds, but lovely all the same.

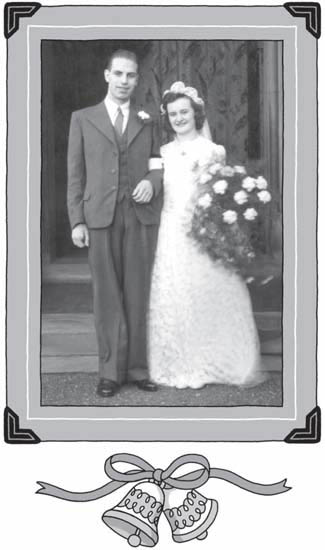

They didn’t hang about once they were engaged. They got married in December. Biddy wore a long white lace dress and a veil, a miracle during wartime, when many brides had to make do with short dresses made out of parachute silk. She had a school friend who now lived in Belfast, where you didn’t need coupons for clothes. She got the length of lace and my grandma made it up for her.

She had little white satin shoes – size three – and a bouquet of white roses. Could they have been real roses in December during the war? No wonder my mother is holding her bouquet so proudly. Harry looks touchingly proud too, with this small pretty dark-haired girl holding his arm. They’d only known each other three months and yet here they were, standing on the steps of St John’s Church in Kingston, promising to love and honour each other for a lifetime.

They had a few days’ honeymoon in Oxford and then they went back to Bath. They’d lived in separate digs before, so now they had to find a new home to start their married life together. They didn’t have any money and there weren’t any houses up for sale anyway. It was wartime.

They went to live with a friend called Vera, who had two children, but when my Mum quickly became pregnant with me, Vera said they’d have to go.

‘No offence, but there’s not room for two prams in my hall. You’ll have to find some other digs.’

They tramped the streets of Bath but my mother had started to show by this time. All the landladies looked at her swollen stomach and shook their heads.

‘No kiddies,’ each said, over and over.

They must have been getting desperate, and now

they

only had one wage between them, because Biddy had to resign from work when people realized she was pregnant. There was no such thing as maternity leave in those days.

Eventually they found two rooms above a hairdresser’s. The landlady folded her arms and sucked her teeth when she saw Biddy’s stomach, but said they could stay as long as she didn’t ever hear the baby crying. She didn’t want her other lodgers disturbed.

Biddy promised I’d be a very quiet baby. I was, reasonably so. Harry came to collect Biddy and me from the hospital. We went back to our two furnished rooms on the bus. We didn’t have a car. We’d have to wait sixteen years for one. But Harry did branch out and buy a motorized tandom bike and sidecar, a weird lopsided contraption. Biddy sensibly considered this too risky for a newborn baby.

I was her top priority now.

Which of my books starts with a heavily pregnant mum trying to find a new home for her daughters?

It’s

The Diamond Girls

. That mum has four daughters already: Martine, Jude, Rochelle and Dixie. She’s about to give birth to the fifth little Diamond and she’s certain this new baby will be a boy.

‘I’ve got a surprise for you girls,’ said Mum. ‘We’re moving.’

We all stared at her. She was flopping back in her chair, slippered feet propped right up on the kitchen table amongst the cornflake bowls, tummy jutting over her skirt like a giant balloon. She didn’t look capable of moving herself as far as the front door. Her scuffed fluffy mules could barely support her weight. Maybe she needed hot air underneath her and then she’d rise gently upwards and float out of the open window.

I’m very fond of that mum, Sue Diamond, but

my

mum would probably call her Common as Muck. Sue believes in destiny and tarot cards and fortune-telling. My mum would think it a Load of Old Rubbish.

I wonder which Diamond daughter you feel I’m most like? I think it’s definitely dreamy little Dixie.

3

Babyhood

BIDDY SETTLED DOWN

happily to being a mother. I was an easy baby. I woke up at night, but at the first wail my mum sat up sleepily, reached for me and started feeding me. She had a lamp on and read to keep herself awake:

Gone with the Wind; Forever Amber; Rebecca

. Maybe I craned my neck round mid-guzzle and tried to read them too. I read all three properly when I was thirteen or so but I wasn’t really a girl for grand passion. Poor Biddy, reading about dashing heroes like Rhett Butler and Max de Winter with Harry snoring on his back beside her in his winceyette pyjamas.

I didn’t cry much during the day. I lay in my pram, peering up at the ceiling. At the first sign of weak sunshine in late February I was parked in the strip of garden outside. All the baby books reckoned fresh air was just as vital as mother’s milk. Babies were left outside in their big Silver Cross prams, sometimes for hours on end. If they cried, they were simply ‘exercising their lungs’. You’d never leave a pram outside in a front garden now. You’d be terrified of strangers creeping in and

wheeling

the baby away. But it was the custom then, and you ‘aired’ your babies just like you did your washing.

There was a

lot

of washing. There were no disposable nappies in those days so all my cloth nappies had to be washed by hand. There were no washing machines either, not for ordinary families like us, anyway. There wasn’t even constant hot water from the tap.

Biddy had to boil the nappies in a large copper pan, stirring them like a horrible soup, and then fishing them out with wooden tongs. Then she’d wash them again and rinse them three times, with a dab of ‘bluebag’ in the last rinse to make them look whiter than white. Then she’d hang them on the washing line to get them blown dry and properly aired. Then she’d pin one on me and I’d wet it and she’d have to start all over again. She had all her own clothes to wash by hand, and Harry’s too – all his white office shirts, and his tennis and cricket gear come the summer – and I had a clean outfit from head to toe every single day, sometimes two or three.

I wore such a lot of clothes too. In winter there was the nappy and rubber pants, and then weird knitted knickers called a pilch, plus a vest and a liberty bodice to protect my chest, and also a binder when I was a very young baby (I think it was meant

to

keep my belly button in place). Then there was a petticoat, and then a long dress down past my feet, and then a hand-knitted fancy matinée jacket. Outside in winter there’d be woolly booties and matching mittens and a bonnet and several blankets and a big crocheted shawl. Perhaps it was no wonder I was a docile baby and didn’t cry much. I could scarcely expand my lungs to draw breath wearing that little lot.

They were all snowy white and every single garment was immaculately ironed even though all I did was lie on them and crease them. My mother took great pride in keeping me clean. She loved it when people admired my pristine appearance when she wheeled me out shopping. She vaguely knew Patricia Dimbleby, Richard Dimbleby’s sister, David and Jonathan Dimbleby’s aunt (all three men are famous broadcasters), and plucked up the courage to ask her for tea.

I wonder what she gave her. Milk was rationed. Biscuits were rationed. Did she manage to make rock cakes using up her whole week’s butter and sugar and egg allowance? Still, the visit was a success, whatever the sacrifice. Sixty years later my mum’s face still glows when she talks about that visit.

‘She positively

gushed

over you. She said she’d never seen such a clean baby, so perfectly kept,

everything

just so. She said I was obviously a dab hand at washing and ironing.’

It’s interesting that the one children’s classic picture book my mother bought for me was Beatrix Potter’s

Mrs Tiggywinkle

. My mother didn’t like animals: ‘Too dirty, too noisy, too smelly.’ She usually turned her nose up at children’s books about animals, but though Mrs Tiggywinkle was undoubtedly a hedgehog, she was also a washerwoman, and a very good one too.

Which baby in one of my books is discovered without any clothes at all on the day she is born?

It’s April, in

Dustbin Baby

. She’s abandoned by her mother, thrust into a dustbin the moment she’s born.

I cry and cry and cry until I’m as red as a raspberry, the veins standing out on my forehead, my wisps of hair damp with effort. I am damp all over because I have no nappy. I have no clothes at all and if I stop crying I will become dangerously cold.

I’ve always wondered what it must be like not to know your own family. Imagine being told to crayon your family tree at school and not having a single name to prop on a branch. April doesn’t know who her mother is, who her father is. She doesn’t know who

she

is. So she sets out on her fourteenth birthday to find out.