Jacky Daydream (25 page)

Authors: Jacqueline Wilson

28

The Eleven Plus

I HAD A

filthy cold the day I took my eleven plus. One of those head-filled-with-fog colds, when you can’t breathe, you can’t hear, you can’t taste, you certainly can’t

think

. I was boiling hot and yet I kept shivering, especially when I was sitting there at my desk, ready to open the exam booklet. I knew I wouldn’t have a hope in hell with the arithmetic part. I felt as if those eight mythical men were digging a hole in my head, shoving their spades up my nostrils, tunnelling under my eyes, shovelling in my ears.

I knew copying was out of the question. I wouldn’t just risk the wrath and sorrow of Marion and her best friend, Jesus. We’d all been told very sternly indeed that anyone caught copying would be drummed out of the exam, the school, the town of Kingston, England, the World, the entire Universe – left to flounder in Space, with every passing alien pointing their three green fingers and hissing, ‘

Cheat!

’

‘Open your paper and begin!’ said Mr Branson. ‘And read the questions

properly

.’

I read the questions. I re-read the questions. I read them till my eyes blurred. Pens were scratching

all

around me. I’d never felt so frightened in my life. I didn’t know the answer to a single problem. I could do the simple adding up and taking away at the beginning. Well, I thought I could. When I picked up my pen at last and tried to write in my first few answers, the figures started wriggling around on the page, doing little whirring dances, and wouldn’t keep still long enough for me to count them up. I couldn’t calculate in my bunged-up head. I had to use my ten fingers, like an infant. I

felt

like an infant. I badly wanted to suck my thumb and rub my hankie over my sore nose, but if Mr Branson saw me sucking my thumb, he’d surely snip it off with his scissors like the long-legged Scissor Man in

Struwwelpeter

. I did try to have a quick nuzzle into my hankie, but it was soggy and disgusting with constant nose-blowing, no use at all.

I could manage the English, just about, but the intelligence test was almost as impenetrable as the arithmetic. The word games were fine, but the number sequences were meaningless and I couldn’t cope with any questions starting:

A is to B as C is to?

Indeed! What did they mean? What did

any

of it mean?

I struggled on, snuffling and sighing, until at long last Mr Branson announced, ‘Time’s up! Put your pens

down

.’

My pen was slippy with sweat. I blew my nose over

and

over again while everyone babbled around me.

‘It was OK, wasn’t it?’ said my new friend Christine.

‘It wasn’t

too

bad,’ said Marion.

‘I liked that poem in the English part,’ said Ann.

‘My pen went all blotchy – do you think it matters?’ said Cherry.

The boys were all boasting that it was easy-peasy, except Julian, who modestly kept quiet.

I kept quiet too.

‘How did

you

get on, Jacky?’

‘I thought it was horrible,’ I sniffed.

‘Oh, rubbish. You’re one of the cleverest. I bet you’ll come out top,’ said Cherry.

‘No I won’t! I couldn’t do half of the arithmetic,’ I said.

‘Neither could I,’ said Christine comfortingly. ‘But you’ll have done all right, just you wait and see.’

Well, I waited. We all had to wait months until the results came through. Then Mr Branson stood at the front of the class with the large dreaded envelope. He opened it up with elaborate ceremony and then scanned it quickly. We sat up straight, hearts thumping. He took our class register and went down the long list of our names, ticking several. Every so often his hand hovered in the air and he made his mouth an O, hissing with horror.

He

had the register at such an angle that we had no way of knowing whether he was up in the As or down in the Ws. We just had to sit there, sweating.

Mr Branson cleared his throat.

‘Well, well, well,’ he said. ‘A lot of shocks and surprises here. Well done,

some

of you. The rest of you should be thoroughly ashamed. Very well, Four A, pin back your ears. I will now go through the register and tell you whether you have – or have not – passed your eleven-plus examination.’

He paused. We waited. I was Jacqueline Aitken then, the first child on the register.

‘Jacky Aitken . . . you have

not

passed your eleven plus,’ said Mr Branson.

I sat still, the edge of the desk pressing into my chest. Mr Branson glared at me, and then worked his way down the register. I couldn’t concentrate. I heard Robert had passed, Raymond had passed, Julian of course had passed – but I didn’t catch any of the girls’ names. I was too concerned with my own terrible failure.

I wanted to cry, but there was no way in the world I was going to let Mr Branson see me weeping. I even managed to meet his eye.

I could face up to him but I didn’t know how I was going to face Biddy and Harry. Biddy had said all the right things. She had tried not to put too much pressure on me. She’d told me simply to do

my

best. But I hadn’t done my best, I’d done my worst. I’d failed.

She

hadn’t failed. She’d passed her eleven plus and gone to Tiffins Girls.

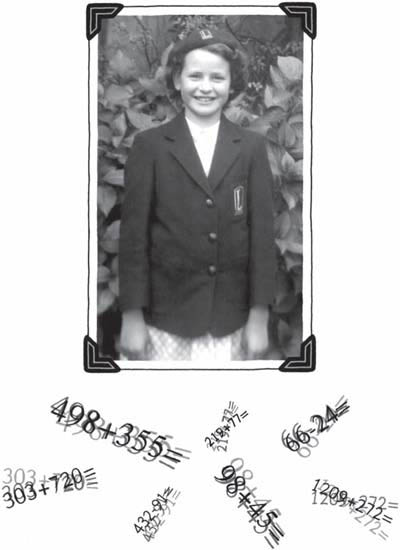

Harry had been sent to a technical school so he was particularly keen for me to have a grammar school education. He’d tried tutoring me at home, working our way through intelligence tests and those terrible men-digging-holes problems. He’d start with his kind voice and he’d promise he wouldn’t get cross. He said if there was anything at all I didn’t understand, I had only to say and he’d go over it again for me. He’d go over it – again and again and again – and I’d struggle to take it all in, but the words started to lose all their sense and the figures were meaningless marks on the page.

‘You’re not

listening

, Jac!’ Harry would say.

‘I am. I am. You said you wouldn’t get cross.’

‘I’m

not

cross,’ Harry insisted, sighing irritably.

He’d say it all again, s-l-o-w-l-y, as if that would somehow make a difference. I’d be just as baffled, and make silly mistakes, until Harry would suddenly lose it.

‘

Are you a MORON?

’ he’d shriek, his fist thumping the page.

I felt I

was

a moron where maths was concerned, but no one seemed to understand that I wasn’t one

deliberately

. Harry spent hours and hours trying

to

coach me even though it had now proved a total waste of time.

I had to tell them as soon as possible to get it over with. I couldn’t ring them. Mobiles weren’t invented. We didn’t even have an ordinary land line at home. Harry possibly had one in the London office but I didn’t know the number. I didn’t know Biddy’s number either, but I knew where her office was. I decided to miss my school dinner and run the two miles to her work to tell her the terrible news.

Poor Biddy. There she was, having a cup of tea and writing beautiful entries in the big accounts book when I burst in on her. Her pen wavered, her tea spilled, but she didn’t care. She thought I’d passed. Surely that was the only reason I’d run such a long way at dinner time.

‘Oh, Jac!’ she said, holding out her arms, her whole face lit up with joy at the thought of her daughter going to grammar school.

‘No, no – I’ve

failed

!’

She was valiant. She kept right on smiling and gave me the hug.

‘Never mind,’ she said. ‘Never you mind. There now.’ She paused. ‘Did you get given a second chance?’

In those days they let all borderline eleven plus failures sit a further exam in the summer, and those who passed had their pick of the secondary schools. You couldn’t get into Tiffins, but it still

wasn

’t to be sniffed at.

I’d been in such a state I hadn’t taken it in. I

had

been given a second chance. I went along to sit the exam a couple of months later. Ironically, we were all sent to Tiffins to do the paper. It was more scary not being in our own environment. No one told us where the lavatories were, so we all fidgeted desperately in our seats as time went by. I can’t remember any men digging holes this time. Perhaps we only had to do an intelligence test. Anyway – this time I passed.

The twins in

Double Act

sit an entrance exam to go to the boarding school Marnock Heights. Which twin passes, Ruby or Garnet?

It’s Garnet – although everyone expected Ruby to pass.

We couldn’t believe it. We thought Miss Jeffreys had got us mixed up.

‘She means me,’ said Ruby. ‘She must mean me.’

‘Yes, it can’t be me,’ I said. ‘Ruby will have got the scholarship.’

‘No,’ said Dad. ‘It’s definitely Garnet.’

‘Let me see the letter!’ Ruby demanded.

Dad didn’t want either of us to see it.

‘It’s addressed to me,’ he said. ‘And it’s plain what it says. There’s no mix-up.’

‘She’s just got our names round the wrong way,’ Ruby insisted. ‘It’s always happening.’

‘Not this time,’ said Rose.

‘Look, it’s absolutely not fair if she’s read the letter too, when it’s got nothing to do with her. She’s not our mother,’ said Ruby.

‘No, but I’m your father, and I want you to calm down, Ruby, and we’ll talk all this over carefully.’

‘Not till you show me the letter!’

‘I’d show both the girls the letter,’ said Rose. ‘They’re not little kids. I think they should see what it says.’

So Dad showed us.

It was like a smack in the face.

Not for me. For Ruby.

Poor Ruby – and poor Garnet too! I hate the next bit, when Ruby refuses to have anything to do with Garnet. I’m glad they make friends again just before Garnet goes off to boarding school. I’ve often wondered what happens next!

29

Fat Pat

I STILL HAD

imaginary friends when I was in the last year of Latchmere but I had many real friends too. I still walked to and from school with Cherry but I didn’t play with her so much. I didn’t play with Ann any more either. She had a new best friend, a tall rangy girl called Glynis. They were always going off together and playing their own elaborate secret games. Ann was prettier than ever, her hair long and glossy and tied with bright satin bows. She wore wonderful short floral dresses with smocking and frilled sleeves. She had frills all over – when she ran, you caught a glimpse of her white frilly knickers. She was the girl we all wanted to be.

Poor Pat was the girl we all shunned. She was the fat girl, Fat Pat, Chubby Cheeks, Lardy Mardy, Greedy Guts, Two-Ton Tessie, Elephant Bum. She wore sensible loose dresses to hide her bulk. It must have been torture for her to have to take off her dress publicly and do PT in her vest and vast knickers. If she’d been half her size she’d have been considered pretty. She had very pink cheeks and long blonde straight hair, almost white. Her plaits

were

always incredibly neat, never a hair out of place, her ribbons tied up all day long.

She had the most beautifully neat handwriting too. She’d lie half across her page, her chubby hand moving slowly, her pink tongue peeping out between her lips – so much effort to make those smooth, even, blue letters on the page.