Janus (16 page)

Authors: Arthur Koestler

soma

pills of

Brave New World

, but a state

of dynamic equilibrium in which the divided house of faith and reason

is reunited and hierarchic order restored.

3

I first published these hopeful speculations -- as the only alternative to

despair that I could (and can) see -- in the concluding chapter of

The Ghost

in the Machine

. Among the many negative criticisms which it brought

in its wake, the one most frequently voiced accused me of proposing the

manufacture of a little pill which would suppress all feeling and emotion

and reduce us to the equanimity of cabbages. This charge, sometimes

uttered with great vehemence, was based on a complete misreading of the

text. What I proposed was not the castration of emotion, but reconciling

emotion and reason which through most of man's schizophrenic history have

been at loggerheads. Not an amputation, but a process of harmonization

which assigns each level of the mind, from visceral impulses to abstract

thought, its appropriate place in the hierarchy. This implies reinforcing

the new brain's power of veto against that type of emotive behaviour --

and that type only

-- which cannot be reconciled with reason, such as

the 'blind' passions of the group-mind. If these could be eradicated,

our species would be safe.

There are blind emotions and visionary emotions. Who in his senses would

advocate doing away with the emotions aroused while listening to Mozart

or looking at a rainbow?

4

Any individual living today who asserted that he had made a pact with the

devil and had intercourse with succubi would be promptly dispatched to

a mental home. Yet not so long ago, belief in such things was taken for

granted and approved by common sense -- i.e., the consensus of opinion,

i.e., the group-mind. Psychopharmacology is playing an increasing part

in the treatment of mental disorders in the clinical sense, such as

individual delusions which affect the critical faculties and are not

sanctioned by the group-mind. But we are concerned with a cure for

the paranoid streak in what we call 'normal people', which is revealed

when they become victims of group-mentality. As we already have drugs to

increase man's suggestibility, it will soon be within our reach to do the

opposite: to reinforce man's critical faculties, counteract misplaced

devotion and that militant enthusiasm, both murderous and suicidal,

which is reflected in history books and the pages of the daily paper.

But who is to decide which brand of devotion is misplaced, and which

beneficial to mankind? The answer seems obvious: a society composed of

autonomous individuals, once they are immunized against the hypnotic

effects of propaganda and thought-control, and protected against their

own suggestibility as 'belief-accepting animals'. But this protection

cannot be provided by counter-propaganda or drop-out attitudes; they

are self-defeating. It can only be done by 'tampering' with human nature

itself to correct its endemic schizophysiological disposition. History

tells us that nothing less will do.

5

Assuming that the laboratories succeed in producing an immunizing

substance conferring mental stability -- how are we to propagate its

global use? Are we to ram it down people's throats, whether they like

it or not?

Again the answer seems obvious. Analgesics, pep pills, tranquillizers,

contraceptives have, for better or worse, swept across the world with

a minimum of publicity or official encouragement. They spread because

people welcomed their effects. The use of a mental stabilizer would

spread not by coercion but by enlightened self-interest; from then on,

developments are as unpredictable as the consequences of any revolutionary

discovery. A Swiss canton may decide, after a public referendum, to add

the new substance to the iodine in the table salt, or the chlorine in the

water supply, for a trial period, and other countries may imitate their

example. There might be an international fashion among the young. In one

way or the other, the simulated mutation would get under way. It is possible

that totalitarian countries would try to resist it. But today even Iron

Curtains have become porous; fashions are spreading irresistibly. And

should there be a transitional period during which one side alone went

ahead, it would gain a decisive advantage because it would be more rational

in its long-term policies, less frightened and less hysterical.

In conclusion, let me quote from

The Ghost in the Machine

:

of things to come.

We can now move to more cheerful horizons.

PART TWO

The Creative Mind

VI

HUMOUR AND WIT

I

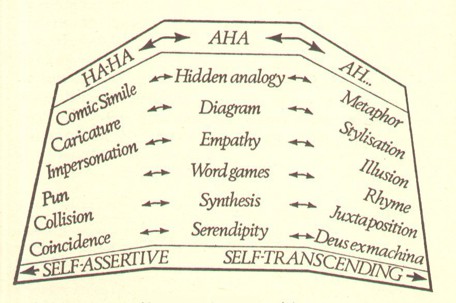

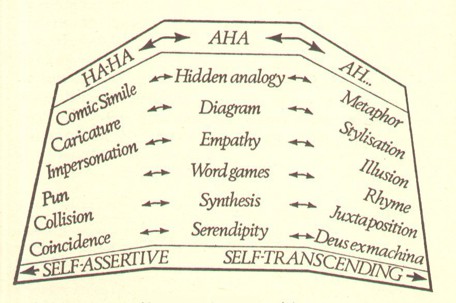

The theory of human creativity which I developed in earlier books

[1]

endeavours to show that all creative activities --

the conscious and unconscious processes underlying the three domains

of artistic originality, scientific discovery and comic inspiration

-- have a basic pattern in common, and to describe that pattern. The

three panels of the triptych on page 110 indicate these three domains,

which shade into each other without sharp boundaries. The meaning of

the diagram will become apparent as the argument unfolds.

and wit. But this will appear less odd if we remember that 'wit is

an ambiguous term, relating to both witticism and to ingenuity or

inventiveness.* The jester and the explorer both live on their wits,

and we shall see that the jester's riddles provide a convenient back-door

entry, as it were, into the inner sanctum of creative originality. Hence

this inquiry will start with an analysis of the comic.** It may

be thought that I have allowed a disproportionate amount of space to

humour, but it is meant to serve, as I said, as a back-door approach to

the creative process in science and art. Besides, it can also be read

as a self-contained essay -- and it may provide the reader with some

light relief.

type of stimulation which tends to elicit the laughter reflex. Spontaneous

laughter is a motor reflex, produced by the coordinated contraction

of fifteen facial muscles in a stereotyped pattern and accompanied

by altered breathing. Electrical stimulation of the

zygomatic

major

, the main lifting muscle of the upper lip with currents of

varying intensity, produces facial expressions ranging from the faint

smile through the broad grin, to the contortions typical of explosive

laughter.

[3]

(The laughter and smile of civilized man is

of course often of a conventional kind where voluntary effort deputizes

for, or interferes with, spontaneous reflex activity; we are concerned,

however, only with the latter.)

faced with several paradoxes. Motor reflexes, such as the contraction of

the pupil of the eye in dazzling light, are simple responses to simple

stimuli, whose value in the service of survival is obvious. But the

involuntary contraction -- of fifteen facial muscles associated with

certain irrepressible noises strikes one as an activity without any

practical value, quite unrelated to the struggle for survival.

Laughter

is a reflex, but unique in that it has no apparent biological utility.

One might call it a luxury reflex. Its only purpose seems to be to

provide temporary relief from the stress of purposeful activities.

of the stimulus and that of the response in humorous transactions. When

a blow beneath the knee-cap causes an automatic upward kick, both

'stimulus' and 'response' function on the same primitive physiological

level, without requiring the intervention of higher mental functions. But

that such a complex mental activity as reading a story by James Thurber

should cause a specific reflex-contraction of the facial musculature

is a phenomenon which has puzzled philosophers since Plato. There is no

clear-cut, predictable response which would tell a lecturer whether he

has succeeded in convincing his listeners; but when he is telling a joke,

laughter serves as an experimental test.

Humour is the only form of

communication in which a stimulus on a high level of complexity produces

a stereotyped, predictable response on the physiological reflex level.

This enables us to use the response as an indicator for the presence of

that elusive quality that we call humour -- as we use the click of the

Geiger counter to indicate the presence of radioactivity. Such a procedure

is not possible in any other form of art; and since the step from the

sublime to the ridiculous is reversible, the study of humour provides the

psychologist with important clues for the study of creativity in general.

tickling to mental titillations of the most varied and sophisticated

kinds. I shall attempt to demonstrate that there is unity in this variety,

a common denominator of a specific and specifiable pattern which reflects

the 'logic' or 'grammar' of humour. A few examples will help to unravel

that pattern.

the last, we discover after a little reflection that the marquis's

behaviour is both unexpected and perfectly logical -- but of a logic

not usually applied to this type of situation. It is the logic of the

division of labour, governed by rules as old as human civilization. But

we expected that his reactions would be governed by a different set of

rules -- the code of sexual morality. It is the sudden clash between

these two mutually exclusive codes of rules -- or associative contexts,

or cognitive holons -- which produces the comic effect. It compels us to

perceive the situation in two self-consistent but incompatible frames of

reference at the same time; it makes us function simultaneously on two

different wave-lengths. While this unusual condition lasts, the event is

not, as is normally the case, associated with a single frame of reference,

but

pills of

Brave New World

, but a state

of dynamic equilibrium in which the divided house of faith and reason

is reunited and hierarchic order restored.

3

I first published these hopeful speculations -- as the only alternative to

despair that I could (and can) see -- in the concluding chapter of

The Ghost

in the Machine

. Among the many negative criticisms which it brought

in its wake, the one most frequently voiced accused me of proposing the

manufacture of a little pill which would suppress all feeling and emotion

and reduce us to the equanimity of cabbages. This charge, sometimes

uttered with great vehemence, was based on a complete misreading of the

text. What I proposed was not the castration of emotion, but reconciling

emotion and reason which through most of man's schizophrenic history have

been at loggerheads. Not an amputation, but a process of harmonization

which assigns each level of the mind, from visceral impulses to abstract

thought, its appropriate place in the hierarchy. This implies reinforcing

the new brain's power of veto against that type of emotive behaviour --

and that type only

-- which cannot be reconciled with reason, such as

the 'blind' passions of the group-mind. If these could be eradicated,

our species would be safe.

There are blind emotions and visionary emotions. Who in his senses would

advocate doing away with the emotions aroused while listening to Mozart

or looking at a rainbow?

4

Any individual living today who asserted that he had made a pact with the

devil and had intercourse with succubi would be promptly dispatched to

a mental home. Yet not so long ago, belief in such things was taken for

granted and approved by common sense -- i.e., the consensus of opinion,

i.e., the group-mind. Psychopharmacology is playing an increasing part

in the treatment of mental disorders in the clinical sense, such as

individual delusions which affect the critical faculties and are not

sanctioned by the group-mind. But we are concerned with a cure for

the paranoid streak in what we call 'normal people', which is revealed

when they become victims of group-mentality. As we already have drugs to

increase man's suggestibility, it will soon be within our reach to do the

opposite: to reinforce man's critical faculties, counteract misplaced

devotion and that militant enthusiasm, both murderous and suicidal,

which is reflected in history books and the pages of the daily paper.

But who is to decide which brand of devotion is misplaced, and which

beneficial to mankind? The answer seems obvious: a society composed of

autonomous individuals, once they are immunized against the hypnotic

effects of propaganda and thought-control, and protected against their

own suggestibility as 'belief-accepting animals'. But this protection

cannot be provided by counter-propaganda or drop-out attitudes; they

are self-defeating. It can only be done by 'tampering' with human nature

itself to correct its endemic schizophysiological disposition. History

tells us that nothing less will do.

5

Assuming that the laboratories succeed in producing an immunizing

substance conferring mental stability -- how are we to propagate its

global use? Are we to ram it down people's throats, whether they like

it or not?

Again the answer seems obvious. Analgesics, pep pills, tranquillizers,

contraceptives have, for better or worse, swept across the world with

a minimum of publicity or official encouragement. They spread because

people welcomed their effects. The use of a mental stabilizer would

spread not by coercion but by enlightened self-interest; from then on,

developments are as unpredictable as the consequences of any revolutionary

discovery. A Swiss canton may decide, after a public referendum, to add

the new substance to the iodine in the table salt, or the chlorine in the

water supply, for a trial period, and other countries may imitate their

example. There might be an international fashion among the young. In one

way or the other, the simulated mutation would get under way. It is possible

that totalitarian countries would try to resist it. But today even Iron

Curtains have become porous; fashions are spreading irresistibly. And

should there be a transitional period during which one side alone went

ahead, it would gain a decisive advantage because it would be more rational

in its long-term policies, less frightened and less hysterical.

In conclusion, let me quote from

The Ghost in the Machine

:

Every writer has a favourite type of imaginary reader, a friendlyThis is the only alternative to despair which I can read into the shape

phantom but highly critical, with whom he is engaged in a continuous,

exhausting dialogue. I feel sure that my friendly phantom-reader has

sufficient imagination to extrapolate from the recent breath-taking

advances of biology into the future, and to concede that the solution

outlined here is in the realm of the possible. What worries me is

that he might be repelled and disgusted by the idea that we should

rely for our salvation on molecular chemistry instead of a spiritual

rebirth. I share his distress, but I see no alternative. I hear him

explain: 'By trying to sell us your Pills, you are adopting that

crudely materialistic attitude and naive scientific hubris which you

pretend to oppose.' I still oppose it. But I do not believe that

it is 'materialistic' to take a realistic view of the condition

of man; nor is it hubris to feed thyroid extracts to children who

would otherwise grow into cretins . . . Like the reader, I would

prefer to set my hopes on moral persuasion by word and example. But

we are a mentally sick race, and as such deaf to persuasion. It

has been tried from the age of the prophets to Albert Schweitzer;

and Swift's anguished cry: 'Not die here in a rage, like a poisoned

rat in a hole,' has acquired an urgency as never before.

Nature has let us down, God seems to have left the receiver off the

hook, and time is running out. To hope for salvation to be synthesised

in the laboratory may seem materialistic, crankish or naive; it

reflects the ancient alchemist's dream to concoct the elixir

vitae. What we expect from it, however, is not eternal life,

but the transformation of homo maniacus into homo sapiens. [2]

of things to come.

We can now move to more cheerful horizons.

PART TWO

The Creative Mind

VI

HUMOUR AND WIT

I

The theory of human creativity which I developed in earlier books

[1]

endeavours to show that all creative activities --

the conscious and unconscious processes underlying the three domains

of artistic originality, scientific discovery and comic inspiration

-- have a basic pattern in common, and to describe that pattern. The

three panels of the triptych on page 110 indicate these three domains,

which shade into each other without sharp boundaries. The meaning of

the diagram will become apparent as the argument unfolds.

and wit. But this will appear less odd if we remember that 'wit is

an ambiguous term, relating to both witticism and to ingenuity or

inventiveness.* The jester and the explorer both live on their wits,

and we shall see that the jester's riddles provide a convenient back-door

entry, as it were, into the inner sanctum of creative originality. Hence

this inquiry will start with an analysis of the comic.** It may

be thought that I have allowed a disproportionate amount of space to

humour, but it is meant to serve, as I said, as a back-door approach to

the creative process in science and art. Besides, it can also be read

as a self-contained essay -- and it may provide the reader with some

light relief.

* 'Wit' stems from witan, understanding, whose roots go back to

the Sanskrit veda, knowledge. The German Witz

means both joke and acumen; it comes from wissen, to know;

Wissenschaft, science, is a close kin to Furwitz and

Aberwitz -- presumption, cheek, and jest. French teaches the

same lesson. Spirituel may either mean witty or spiritually

profound; 'to amuse' comes from to muse' (a-muser), and a

witty remark is a jeu d'esprit -- a playful, mischievous

form of discovery.

** This chapter is based on the summary of the theory which I contributed

to the fifteenth edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica. [2]

type of stimulation which tends to elicit the laughter reflex. Spontaneous

laughter is a motor reflex, produced by the coordinated contraction

of fifteen facial muscles in a stereotyped pattern and accompanied

by altered breathing. Electrical stimulation of the

zygomatic

major

, the main lifting muscle of the upper lip with currents of

varying intensity, produces facial expressions ranging from the faint

smile through the broad grin, to the contortions typical of explosive

laughter.

[3]

(The laughter and smile of civilized man is

of course often of a conventional kind where voluntary effort deputizes

for, or interferes with, spontaneous reflex activity; we are concerned,

however, only with the latter.)

faced with several paradoxes. Motor reflexes, such as the contraction of

the pupil of the eye in dazzling light, are simple responses to simple

stimuli, whose value in the service of survival is obvious. But the

involuntary contraction -- of fifteen facial muscles associated with

certain irrepressible noises strikes one as an activity without any

practical value, quite unrelated to the struggle for survival.

Laughter

is a reflex, but unique in that it has no apparent biological utility.

One might call it a luxury reflex. Its only purpose seems to be to

provide temporary relief from the stress of purposeful activities.

of the stimulus and that of the response in humorous transactions. When

a blow beneath the knee-cap causes an automatic upward kick, both

'stimulus' and 'response' function on the same primitive physiological

level, without requiring the intervention of higher mental functions. But

that such a complex mental activity as reading a story by James Thurber

should cause a specific reflex-contraction of the facial musculature

is a phenomenon which has puzzled philosophers since Plato. There is no

clear-cut, predictable response which would tell a lecturer whether he

has succeeded in convincing his listeners; but when he is telling a joke,

laughter serves as an experimental test.

Humour is the only form of

communication in which a stimulus on a high level of complexity produces

a stereotyped, predictable response on the physiological reflex level.

This enables us to use the response as an indicator for the presence of

that elusive quality that we call humour -- as we use the click of the

Geiger counter to indicate the presence of radioactivity. Such a procedure

is not possible in any other form of art; and since the step from the

sublime to the ridiculous is reversible, the study of humour provides the

psychologist with important clues for the study of creativity in general.

tickling to mental titillations of the most varied and sophisticated

kinds. I shall attempt to demonstrate that there is unity in this variety,

a common denominator of a specific and specifiable pattern which reflects

the 'logic' or 'grammar' of humour. A few examples will help to unravel

that pattern.

(a) A masochist is a person who likes a cold shower in the morning,

so he takes a hot one.

(b) An English lady, on being asked by a friend what she thought of

her departed husband's whereabouts: 'Well, I suppose the poor soul

is enjoying eternal bliss, but I wish you wouldn't talk about such

unpleasant subjects.'*

* This is a variant of Russell's anecdote

in the Prologue.

(c) A doctor comforts his patient: 'You have a very serious disease.

Of ten persons who catch it only one survives. It is lucky you

came to me, for I have recently had nine patients with this disease

and they all died of it.'

(d) Dialogue in a film by Claude Bern:

'Sir, I would like to ask for your daughter's hand.'

'Why not? You have akeady had the rest.'

(e) A marquis at the court of Louis XV unexpectedly returned from a

journey and, on entering his wife's boudoir, found her in the arms

of a bishop. After a moment's hesitation the marquis walked calmly

to the window, leaned out and began going through the motions of

blessing the people in the Street.

'What are you doing?' cried the anguished wife.

'Monseigneur is performing my functions, so I am performing his.'

the last, we discover after a little reflection that the marquis's

behaviour is both unexpected and perfectly logical -- but of a logic

not usually applied to this type of situation. It is the logic of the

division of labour, governed by rules as old as human civilization. But

we expected that his reactions would be governed by a different set of

rules -- the code of sexual morality. It is the sudden clash between

these two mutually exclusive codes of rules -- or associative contexts,

or cognitive holons -- which produces the comic effect. It compels us to

perceive the situation in two self-consistent but incompatible frames of

reference at the same time; it makes us function simultaneously on two

different wave-lengths. While this unusual condition lasts, the event is

not, as is normally the case, associated with a single frame of reference,

but

Other books

Will Eisner by Michael Schumacher

X Descending by Lambright, Christian

Guns to the Far East by V. A. Stuart

The Russian Affair by Michael Wallner

Bucking Bronc Lodge 04 - Cowboy Cop by Rita Herron

The Christmas Knight by Michele Sinclair

Oceans of Red Volume One by Cross, Willow

Spacer Clans Adventure 1: Naero's Run by Mason Elliott

Bedding the Enemy by Mary Wine

Koran Curious - A Guide for Infidels and Believers by C.J. Werleman