Janus (5 page)

Authors: Arthur Koestler

2

Nevertheless, reductionism proved an eminently successful method within

its limited range of applicability in the exact sciences, while its

antithesis, holism, never really got off the ground. Holism may be defined

by the statement that the whole is more than the sum of its parts. The

term was coined by Jan Smuts in the 1920s in a remarkable book

[4]

which for a while enjoyed great popularity. But holism never got a grip

on academic science* -- partly because it went against the Zeitgeist,

partly perhaps because it represented more of a philosophical than an

empirical approach and did not lend itself to laboratory tests.

a cul-de-sac. 'A rose is a rose is a rose' may be regarded as a holistic

statement, but it tells us no more about the rose than the formulae of

its chemical constituents. For our inquiry we need a third approach,

beyond reductionism and holism, which incorporates the valid aspects of

both. It must start with the seemingly abstract yet fundamental problem

of the relations between the whole and its parts -- any 'whole', whether

the universe or human society, and any 'part', whether an atom or a

human being. This may seem an odd, not to say perverse, way to get at

a diagnosis of man's condition, but the reader will eventually realize,

I hope, that the apparent detour though the theoretical considerations

in the present chapter may be the shortest way out of the labyrinth.

3

To start with a deceptively simple question: what exactly do we mean by the

familiar words 'part' and 'whole'? 'Part' conveys the meaning of something

fragmentary and incomplete, which by itself has no claim to autonomous

existence. On the other hand, a 'whole' is considered as something complete

in itself which needs no further explanation. However, contrary to these

deeply ingrained habits of thought and their reflection in some philosophical

schools, 'parts' and 'wholes' in an absolute sense do not exist anywhere,

either in the domain of living organisms, or in social organizations,

or in the universe at large.

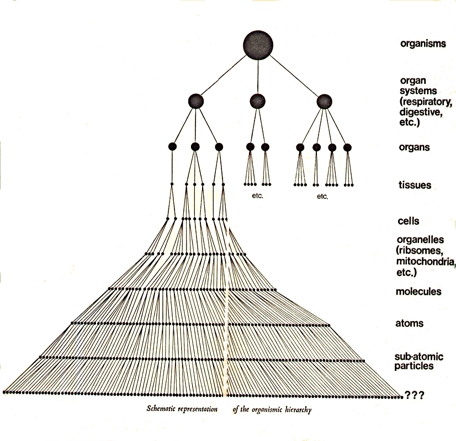

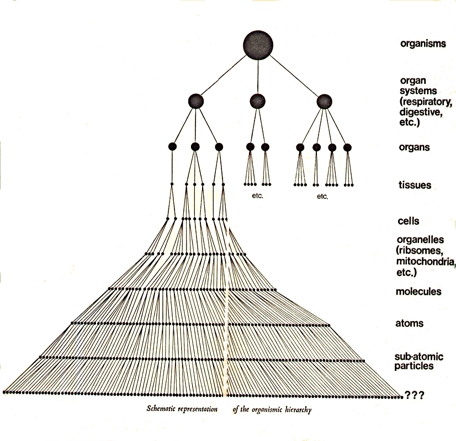

A living organism is not an aggregation of elementary parts, and its

activities cannot be reduced to elementary 'atoms of behaviour' forming

a chain of conditioned responses. In its bodily aspects, the organism

is a whole consisting of 'sub-wholes', such as the circulatory system,

digestive system, etc., which in turn branch into sub-wholes of a lower

order, such as organs and tissues -- and so down to individual cells,

and to the organelles inside the cells. In other words, the structure

and behaviour of an organism cannot be explained by, or 'reduced to',

elementary physico-chemical processes; it is a multi-levelled, stratified

hierarchy of sub-wholes, which can be conveniently diagrammed as a pyramid

or an inverted tree, where the sub-wholes form the nodes, and the branching

lines symbolize channels of communication and control: see diagram

.

on whatever level, is a sub-whole or 'holon' in its own right -- a stable,

integrated structure, equipped with self-regulatory devices and enjoying

a considerable degree of autonomy or self-government. Cells, muscles,

nerves, organs, all have their intrinsic rhythms and patterns of activity,

often manifested spontaneously without external stimulation; they are

subordinated as parts to the higher centres in the hierarchy, but at

the same time function as quasi-autonomous wholes. They are Janus-faced.

The face turned upward, toward the higher levels, is that of a dependent

part; the face turned downward, towards its own constituents, is that

of a whole of remarkable self-sufficiency.

pacemakers, capable of taking over from each other when the need arises.

Other major organs are equipped with different types of coordinating

devices and feedback controls. Their autonomy is convincingly demonstrated

by transplant surgery. At the beginning of our century, Alexis Carrell

showed that a minute strip of tissue taken from the heart of a chicken

embryo and put into a nutrient solution will go on pulsating for years.

Since then, whole organs were shown to be capable of functioning as

quasi-independent wholes when taken out of the body and kept in vitro,

or transplanted into another body. And as we descend the steps of the

hierarchy to the lowest level observable through the electron microscope,

we come upon sub-cellular structures -- organelles -- which are neither

'simple' nor 'elementary', but systems of staggering complexity. Each of

these minuscule parts of a cell functions as a self-governing whole in its

own right, each apparently obeying a built-in

code of rules

. One type,

or tribe, of organelles looks after the cell's growth, others after its

energy supply, reproduction, communication, and so on. The mitochondria,

for instance, are power plants which extract energy from nutrients by a

chain of chemical reactions involving some fifty different steps; and a

single cell may have up to five thousand such power plants. The activities

of a mitochondrion can be switched on or off by controls on higher levels;

but once triggered into action it will follow its own code of rules. It

cooperates with other organdies in keeping the cell happy, but at the

same time each mitochondrion is a law unto itself, an autonomous unit

which will assert its individuality even if the cell around it is dying.

preconceptions of the nineteenth century -- the world as a billiard

table of colliding atoms -- and to realize that hierarchic organization

is a fundamental principle of living nature; that it is 'the essential

and distinguishing characteristic of life' (Pattee)

[5]

; and that

it is 'a real phenomenon, presented to us by the biological object,

and not the fiction of a speculative mind' (P. Weiss).

[6]

It is at the same time a conceptual tool which on some occasions acts as

an Open Sesame.

All complex structures and processes of a relatively

stable character display hierarchic organization

, regardless whether

we consider galactic systems, living organisms and their activities,

or social organizations. The tree diagram with its series of levels

can be used to represent the evolutionary branching of species into

the 'tree of life'; or the stepwise differentiation of tissues and

integration of functions in the development of the embryo. Anatomists

use the tree diagram to demonstrate the locomotor hierarchy of limbs,

joints, individual muscles, and so down to fibres, fibrils and filaments

of contractile proteins. Ethologists use it to illustrate the various

sub-routines and action-patterns involved in such complex instinctive

activities as a bird building a nest; but it is also an indispensable

tool to the new school of psycholinguistics started by Chomsky. It is

equally indispensable for an understanding of the processes by which the

chaotic stimuli impinging on our sense organs are filtered and classified

in their ascent though the nervous system into consciousness. Lastly,

the branching tree illustrates the hierarchic ordering of knowledge

in the subject-index of library catalogues -- and the personal memory

stores inside our skulls.

that it is logically empty. I hope to show that this is not the case,

and that the search for the fundamental properties, or laws, which all

these varied hierarchies have in common amounts to more than a play on

superficial analogies -- or to riding a hobby horse. It should rather be

called an exercise in General Systems Theory -- that relatively recent

inter-disciplinary school, founded by von Bertalanffy, whose purpose is

to construct theoretical models and discover general principles which

are universally applicable to biological, social and symbolic systems

of any kind -- in other words, a search for common denominators in the

flux of phenomena, for unity-in-diversity.

emphasized the importance of recognizing hierarchically ordered 'levels of

organization', and the emergence on each higher level of new 'organizing

relations' between (sub) wholes of greater complexity, whose properties

cannot be reduced to, nor predicted from, the lower level

. To quote

Needham again:

because it implied that the biological laws which govern life are

qualitatively different from the laws of physics which govern inanimate

matter, and that accordingly life cannot be 'reduced' to the blind dance

of atoms; and similarly, that the mentality of man is qualitatively

different from the conditioned responses of Pavlov's dogs or Skinner's

rats, which the dominant school in psychology considered as the paradigms

of human behaviour. Harmless as the word 'hierarchy' sounded, it turned

out to be subversive. It did not even appear in the index of most modern

textbooks of psychology or biology.

concept of hierarchic organization was an indispensable prerequisite --

a

conditio sine qua non

-- of any methodical attempt to bring unity

into the diversity of science, and might eventually lead to a coherent

philosophy of nature -- which at present is conspicuous by its absence.

author, expressed in several books in which 'the ubiquitous hierarchy'

[9] played a major, and often dominant part. Taken together, the relevant

passages would add up to a fairly comprehensive textbook on hierarchic

order (which may see the light some day). But this is not the purpose

of the present volume. As already said, the hierarchic approach is a

conceptual tool -- not an end in itself, but a key capable of opening

some of nature's combination-locks which stubbornly resist other methods.*

insight into the way it works. The present chapter is meant to convey

some of the basic principles of hierarchic thought in order to provide

a platform or runway for the more speculative flights that follow.

from the insect state to the Pentagon, we shall find that it is

hierarchically structured; the same applies to the individual organism,

and, less obviously, to its innate and acquired skills. However, to prove

the validity and significance of the model, it must be shown that there

exist specific principles and laws which apply (a) to all levels of a

given hierarchy, and (b) to hierarchies in different fields -- in other

words, which define the term 'hierarchic order'. Some of these principles

might appear self-evident, others rather abstract; taken together,

they form the stepping stones for a new approach to some old problems.

away from the traditional misuse of the words 'whole' and 'part',

one is compelled to operate with such awkward terms as 'sub-whole', or

'part-whole', 'sub-structures', 'sub-skills', 'sub-assemblies', and so

forth. To avoid these jarring expressions, I proposed, some years ago

[10]

, a new term to designate those Janus-faced entities

on the intermediate levels of any hierarchy, which can be described

either as wholes or as parts, depending on the way you look at them

from 'below' or from 'above'. The term I proposed was the 'holon',

from the Greek

holos

= whole, with the suffix

on

, which,

as in proton or neutron, suggests a particle or part.

Nevertheless, reductionism proved an eminently successful method within

its limited range of applicability in the exact sciences, while its

antithesis, holism, never really got off the ground. Holism may be defined

by the statement that the whole is more than the sum of its parts. The

term was coined by Jan Smuts in the 1920s in a remarkable book

[4]

which for a while enjoyed great popularity. But holism never got a grip

on academic science* -- partly because it went against the Zeitgeist,

partly perhaps because it represented more of a philosophical than an

empirical approach and did not lend itself to laboratory tests.

* Except indirectly through Gestalt psychology.In fact both reductionism and holism, if taken as sole guides, lead into

a cul-de-sac. 'A rose is a rose is a rose' may be regarded as a holistic

statement, but it tells us no more about the rose than the formulae of

its chemical constituents. For our inquiry we need a third approach,

beyond reductionism and holism, which incorporates the valid aspects of

both. It must start with the seemingly abstract yet fundamental problem

of the relations between the whole and its parts -- any 'whole', whether

the universe or human society, and any 'part', whether an atom or a

human being. This may seem an odd, not to say perverse, way to get at

a diagnosis of man's condition, but the reader will eventually realize,

I hope, that the apparent detour though the theoretical considerations

in the present chapter may be the shortest way out of the labyrinth.

3

To start with a deceptively simple question: what exactly do we mean by the

familiar words 'part' and 'whole'? 'Part' conveys the meaning of something

fragmentary and incomplete, which by itself has no claim to autonomous

existence. On the other hand, a 'whole' is considered as something complete

in itself which needs no further explanation. However, contrary to these

deeply ingrained habits of thought and their reflection in some philosophical

schools, 'parts' and 'wholes' in an absolute sense do not exist anywhere,

either in the domain of living organisms, or in social organizations,

or in the universe at large.

A living organism is not an aggregation of elementary parts, and its

activities cannot be reduced to elementary 'atoms of behaviour' forming

a chain of conditioned responses. In its bodily aspects, the organism

is a whole consisting of 'sub-wholes', such as the circulatory system,

digestive system, etc., which in turn branch into sub-wholes of a lower

order, such as organs and tissues -- and so down to individual cells,

and to the organelles inside the cells. In other words, the structure

and behaviour of an organism cannot be explained by, or 'reduced to',

elementary physico-chemical processes; it is a multi-levelled, stratified

hierarchy of sub-wholes, which can be conveniently diagrammed as a pyramid

or an inverted tree, where the sub-wholes form the nodes, and the branching

lines symbolize channels of communication and control: see diagram

on whatever level, is a sub-whole or 'holon' in its own right -- a stable,

integrated structure, equipped with self-regulatory devices and enjoying

a considerable degree of autonomy or self-government. Cells, muscles,

nerves, organs, all have their intrinsic rhythms and patterns of activity,

often manifested spontaneously without external stimulation; they are

subordinated as parts to the higher centres in the hierarchy, but at

the same time function as quasi-autonomous wholes. They are Janus-faced.

The face turned upward, toward the higher levels, is that of a dependent

part; the face turned downward, towards its own constituents, is that

of a whole of remarkable self-sufficiency.

pacemakers, capable of taking over from each other when the need arises.

Other major organs are equipped with different types of coordinating

devices and feedback controls. Their autonomy is convincingly demonstrated

by transplant surgery. At the beginning of our century, Alexis Carrell

showed that a minute strip of tissue taken from the heart of a chicken

embryo and put into a nutrient solution will go on pulsating for years.

Since then, whole organs were shown to be capable of functioning as

quasi-independent wholes when taken out of the body and kept in vitro,

or transplanted into another body. And as we descend the steps of the

hierarchy to the lowest level observable through the electron microscope,

we come upon sub-cellular structures -- organelles -- which are neither

'simple' nor 'elementary', but systems of staggering complexity. Each of

these minuscule parts of a cell functions as a self-governing whole in its

own right, each apparently obeying a built-in

code of rules

. One type,

or tribe, of organelles looks after the cell's growth, others after its

energy supply, reproduction, communication, and so on. The mitochondria,

for instance, are power plants which extract energy from nutrients by a

chain of chemical reactions involving some fifty different steps; and a

single cell may have up to five thousand such power plants. The activities

of a mitochondrion can be switched on or off by controls on higher levels;

but once triggered into action it will follow its own code of rules. It

cooperates with other organdies in keeping the cell happy, but at the

same time each mitochondrion is a law unto itself, an autonomous unit

which will assert its individuality even if the cell around it is dying.

preconceptions of the nineteenth century -- the world as a billiard

table of colliding atoms -- and to realize that hierarchic organization

is a fundamental principle of living nature; that it is 'the essential

and distinguishing characteristic of life' (Pattee)

[5]

; and that

it is 'a real phenomenon, presented to us by the biological object,

and not the fiction of a speculative mind' (P. Weiss).

[6]

It is at the same time a conceptual tool which on some occasions acts as

an Open Sesame.

All complex structures and processes of a relatively

stable character display hierarchic organization

, regardless whether

we consider galactic systems, living organisms and their activities,

or social organizations. The tree diagram with its series of levels

can be used to represent the evolutionary branching of species into

the 'tree of life'; or the stepwise differentiation of tissues and

integration of functions in the development of the embryo. Anatomists

use the tree diagram to demonstrate the locomotor hierarchy of limbs,

joints, individual muscles, and so down to fibres, fibrils and filaments

of contractile proteins. Ethologists use it to illustrate the various

sub-routines and action-patterns involved in such complex instinctive

activities as a bird building a nest; but it is also an indispensable

tool to the new school of psycholinguistics started by Chomsky. It is

equally indispensable for an understanding of the processes by which the

chaotic stimuli impinging on our sense organs are filtered and classified

in their ascent though the nervous system into consciousness. Lastly,

the branching tree illustrates the hierarchic ordering of knowledge

in the subject-index of library catalogues -- and the personal memory

stores inside our skulls.

that it is logically empty. I hope to show that this is not the case,

and that the search for the fundamental properties, or laws, which all

these varied hierarchies have in common amounts to more than a play on

superficial analogies -- or to riding a hobby horse. It should rather be

called an exercise in General Systems Theory -- that relatively recent

inter-disciplinary school, founded by von Bertalanffy, whose purpose is

to construct theoretical models and discover general principles which

are universally applicable to biological, social and symbolic systems

of any kind -- in other words, a search for common denominators in the

flux of phenomena, for unity-in-diversity.

The hierarchy of relations, from the molecular structure of carbon

compounds to the equilibrium of species and ecological wholes,

will perhaps be the leading idea of the future. [7]

emphasized the importance of recognizing hierarchically ordered 'levels of

organization', and the emergence on each higher level of new 'organizing

relations' between (sub) wholes of greater complexity, whose properties

cannot be reduced to, nor predicted from, the lower level

. To quote

Needham again:

Once we adopt the general picture of the universe as a series of

levels of organisation and complexity, each level having unique

properties of structure and behaviour, which, though depending on the

properties of the constituent elements, appear only when these are

combined into the higher whole, we see that there are qualitatively

different laws holding good at each levels. [8]

because it implied that the biological laws which govern life are

qualitatively different from the laws of physics which govern inanimate

matter, and that accordingly life cannot be 'reduced' to the blind dance

of atoms; and similarly, that the mentality of man is qualitatively

different from the conditioned responses of Pavlov's dogs or Skinner's

rats, which the dominant school in psychology considered as the paradigms

of human behaviour. Harmless as the word 'hierarchy' sounded, it turned

out to be subversive. It did not even appear in the index of most modern

textbooks of psychology or biology.

concept of hierarchic organization was an indispensable prerequisite --

a

conditio sine qua non

-- of any methodical attempt to bring unity

into the diversity of science, and might eventually lead to a coherent

philosophy of nature -- which at present is conspicuous by its absence.

author, expressed in several books in which 'the ubiquitous hierarchy'

[9] played a major, and often dominant part. Taken together, the relevant

passages would add up to a fairly comprehensive textbook on hierarchic

order (which may see the light some day). But this is not the purpose

of the present volume. As already said, the hierarchic approach is a

conceptual tool -- not an end in itself, but a key capable of opening

some of nature's combination-locks which stubbornly resist other methods.*

* Cf. also Jevons: 'The organisation hierarchy, forming as it does a

bridge between parts and whole, is one of the really vital, central

concepts of biology.' [11]

insight into the way it works. The present chapter is meant to convey

some of the basic principles of hierarchic thought in order to provide

a platform or runway for the more speculative flights that follow.

from the insect state to the Pentagon, we shall find that it is

hierarchically structured; the same applies to the individual organism,

and, less obviously, to its innate and acquired skills. However, to prove

the validity and significance of the model, it must be shown that there

exist specific principles and laws which apply (a) to all levels of a

given hierarchy, and (b) to hierarchies in different fields -- in other

words, which define the term 'hierarchic order'. Some of these principles

might appear self-evident, others rather abstract; taken together,

they form the stepping stones for a new approach to some old problems.

away from the traditional misuse of the words 'whole' and 'part',

one is compelled to operate with such awkward terms as 'sub-whole', or

'part-whole', 'sub-structures', 'sub-skills', 'sub-assemblies', and so

forth. To avoid these jarring expressions, I proposed, some years ago

[10]

, a new term to designate those Janus-faced entities

on the intermediate levels of any hierarchy, which can be described

either as wholes or as parts, depending on the way you look at them

from 'below' or from 'above'. The term I proposed was the 'holon',

from the Greek

holos

= whole, with the suffix

on

, which,

as in proton or neutron, suggests a particle or part.

Other books

Charlie Johnson in the Flames by Michael Ignatieff

Organize Your Corpses by Mary Jane Maffini

Red Ridge Pack 1 Pack of Lies by Sara Dailey, Staci Weber

Blue Violet by Abigail Owen

Familiar Desires: 5 (Protective Affairs) by Rebecca Airies

Written in Blood by Collett, Chris

Shadow Cave by Angie West

Rapunzelle: an Everland Ever After Tale by Caroline Lee

River of Death by Alistair MacLean

The Dead Beat by Doug Johnstone