Kaboom (47 page)

Authors: Matthew Gallagher

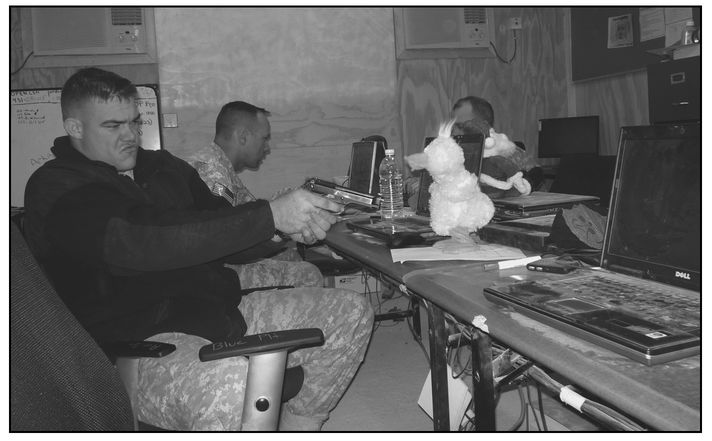

Lieutenant Mongo does not take kindly to a stuffed dancing duck in the Alpha Company tactical operations center and pulls his M9 pistol on it. Luckily, the rest of us were able to intervene before the toy was shot.

Our role in the elections appeared and felt murky. On one hand, Higher told us that maintaining the peace for the local populace remained our top priority; thus, we would flood the urban areas with presence patrols. On the other hand, the military establishment knew how vital it was for us to stay away from the actual polling sites so as to not project the image that we were interfering with the voting process. Practically speaking, this meant that all able-bodied soldiers rolled out of the wire on election day, parked their

Strykers in an isolated corner far away from the polling sites, and waited for something to go wrong.

Strykers in an isolated corner far away from the polling sites, and waited for something to go wrong.

To patrol all of the towns and cities in our AO, Captain Frowny-Face sent the mortarmen/tanker combo platoon to Boob al-Sham and Sabah Qasar, while assigning Lieutenant Dirty Jerz's platoon to East Hussaniyah and Lieutenant Mongo's platoon to West Hussaniyah. Meanwhile, our makeshift Headquarters platoon rotated between the three areas, thus maximizing American presence in anticipation of the potential attacks being reported. Iraqi security forces manned the actual polling sites we so desperately avoided, their latest test of self-sufficiency and independent competence. The government had held early voting three days earlier for the Iraqi security forces and our interpreters, for which we helped provide security.

The polls in the Istalquaal region opened at eight in the morning, so after applying typical army logic and backward planning, we found ourselves out in sector three hours early, at five. I sat in the back of Captain Frowny-Face's Stryker, wedged in tightly between Lieutenant Rant and Specialist Gonzo, avoiding the temptation to lean on the butt of my rifle and sleep. Specialist Wildebeest sat across from us, head cocked back and eyes closed, with a creek of drool rolling down his chin.

“Tired, sir?” Specialist Gonzo asked with a grin, while stifling a yawn of his own. More than any other of my soldiers, he had an uncanny ability to goad hyperbole out of me.

“Yes,” I replied. “More tired than any human being ever has been in the history of prematurely ejaculating army missions.”

Specialist Gonzo laughed, but I wasn't even sure what my statement meant. I had only slept three hours the night before, so I didn't really care, either.

“That doesn't make any sense,” he told me.

I nodded in agreement. “Think about it.”

Our bantering stirred Lieutenant Rant out of his daze. “Gonzo,” he said, “no one wants to hear about your days as a professional knife fighter in Tijuana.”

We all laughed. “I'll remember that one, next time your computer breaks,” Specialist Gonzo replied. “Just 'cause I'm Mexican? I mean, I don't make any saltine jokes about you crackers.”

Lieutenant Rant and I stared at each other awkwardly, not relaxing until Specialist Gonzo started cackling. “I'm just fucking around with you, sir,” he said. “But seriously, I will shiv you and take your hubcaps.”

We spent the next seven hours bouncing between Hussaniyah, Boob al-Sham, and Sabah Qasar, checking with the platoon leaders and platoon sergeants on the ground. Concurrently, the battalion TOC radioed polling-site updates every hour that the Iraqi security forces fed them back at the FOB. With nearly twenty polling sites spread across the three urban centers, we skeptically figured somethingâin this case an IED attack, a drive-by shooting, or an assassinationâwas bound to happen. But by the time high noon rolled around and the bright ball in the sky blared down on us with maximum attention, we had only heard positive things regarding both the voter turnout and the Iraqis' successfully keeping the peace. Captain Frowny-Face asked the battalion TOC how they knew all of this. They informed him that the reports came from the various brigade and battalion leaders, who were visiting the polling sites, apparently immune to the order put out about the polls.

“I guess I missed that paragraph in the operations order,” Lieutenant Rant quipped, “the one that granted field grades exemptions.”

I opened my mouth to follow with a wisecrack of my own, but one look from Captain Frowny-Face halted that plan. I shrugged my shoulders instead and opened up an MRE, fishing out the sliced pears and the candy.

After swinging through West Hussaniyah, where we found Lieutenant Mongo and some members of his platoon kicking around a soccer ball with local children, we drove south on Route Dover, linking up with the combo platoon in Boob al-Sham. They had staged their vehicles at the newly constructed burn pit, built in an attempt to bring scheduled garbage collection to the town. We all dismounted and met SFC C outside.

“Anything going on down here?” Captain Frowny-Face asked.

“Sir, we haven't seen or heard shit,” SFC C replied while spitting out some dip. “Unless you count kids throwing rocks at a goat.”

“That's it?”

“We've seen a fair amount of adults walking toward the school, where the poll site is.”

“If you guys get bored, feel free to patrol around. Just stay clear of that school.”

“Roger, sir. How long you figure we're going to stay out here?”

Captain Frowny-Face shook his head. “Division wants us out here at least an hour after the polls close, so plan on 1900.”

SFC C smiled widely. “Good stuff. It's not like we got anyplace else to go.”

I turned to Lieutenant Rant. “See man, false motivation is always better than no motivation at all. SFC C is truly a pioneer in this field.”

We continued the mission until 1930, when Captain Frowny-Face gave the word to move back to JSS Istalquaal. According to the Iraqis, the only significant events occurred in East Hussaniyah, where many local-nationals found themselves omitted from the ballot list. When told he couldn't vote, one of them threatened to blow the school up, resulting in his immediate detention by the Iraqi police. Every one of us felt exhausted by the long, boring day, and I passed out in my bed with my uniform still on, barely getting my boots off.

The Iraqi government released the results of the elections over a week later. A new round of threats resulted, as did another round of those threats proving false. Despite the lack of a major political protest against the elections, only about half of eligible Iraqis voted, causing Lieutenant Rant and me to observe that they had embraced the most democratic and American of options available to themâapathy. Sadrists won a minority share of seats in parliament, including five seats in the Baghdad governorate. Al-Maliki's Islamic Dawa Party, as a part of the Shia United Iraqi Alliance, maintained a plurality of seats, ensuring he'd continue to serve as prime minister. The various Sunni parties did reasonably well, especially in the Anbar Province in the far west.

We didn't care about any of that, though, at the time. The next day, after a joint targeting meeting with the National Police, I played a few games of helicopter and then watched the Super Bowl on the Armed Forces Network. General Odierno, General Petraeus's replacement as commander of Multinational Force-Iraq, or MNF-I, granted us the right to drink two legitimate beers during the Super Bowl. I drank two Guinnesses and passed out in my bed halfway through the second quarter. It had been over seven months since I'd left Europe and drunk real alcohol, so I didn't feel any shame for its quick effects on me. I didn't wake up at all during that night, which proved a most welcome change from the norm.

MASKS“Telling a terp that his country is safe when he doesn't feel it's safe is as pretentious as it gets,” said an army captain in Baghdad who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he was criticizing his superiors. “The terp-mask thing is just the latest disconnect between

what happens on the ground and what people want to be happening on the ground. We're in full-on dress rehearsal now. I think we're in such a hurry to get out of here, we're wanting this place to be safer than it really is.”

what happens on the ground and what people want to be happening on the ground. We're in full-on dress rehearsal now. I think we're in such a hurry to get out of here, we're wanting this place to be safer than it really is.”

So read an article that ran in the

Washington Post

on February 13, written by an old acquaintance and new Facebook friend, Ernesto Londono. The article recapped a series of events that had occurred in Iraq over the previous six months with regard to a ban on interpreters wearing masks to hide their identities while on mission. The ban had technically been initiated in September, although in my experience most junior leaders ignored it openly and allowed their terps full discretion of when and where they wore a mask. Occasionally, field grades would point out the discrepancy, and if anyone of higher rank than that came around, the terps went sans mask, but 90 percent of the time, the ban meant nothing on the execution level. When the

Washington Post

ran an article about the ban in mid-November, citing its impracticality and the dangers posed to interpreters, Congress initiated an inquiry. The outcome led to the Pentagon's delegating authority to battalion commandersâspecifically stating that they couldn't delegate it themselvesâto lift the ban for specific patrols and in special cases.

Washington Post

on February 13, written by an old acquaintance and new Facebook friend, Ernesto Londono. The article recapped a series of events that had occurred in Iraq over the previous six months with regard to a ban on interpreters wearing masks to hide their identities while on mission. The ban had technically been initiated in September, although in my experience most junior leaders ignored it openly and allowed their terps full discretion of when and where they wore a mask. Occasionally, field grades would point out the discrepancy, and if anyone of higher rank than that came around, the terps went sans mask, but 90 percent of the time, the ban meant nothing on the execution level. When the

Washington Post

ran an article about the ban in mid-November, citing its impracticality and the dangers posed to interpreters, Congress initiated an inquiry. The outcome led to the Pentagon's delegating authority to battalion commandersâspecifically stating that they couldn't delegate it themselvesâto lift the ban for specific patrols and in special cases.

While theoretically this sounded like good news for the terps, it carried the adverse effect of focusing concentrated attention on the ban for all patrols, and suddenly the mask ban became a hot-button issue and was to be enforced at all levels. From November to the end of our deployment, allowing a terp to wear a mask without the commander's exemption became the equivalent of shooting a civilian or negligently discharging your weapon, in terms of bureaucratic accountability and the ass chewings levied by Higher. At JSS Istalquaal, Barry, in particular, openly feared for his life because he couldn't wear a mask in certain areas. After determining that he needed money for his mother's new house, though, he backed off his threats to quit as an interpreter for Coalition forces. Three other terps, one of whom had worked with us for three years, did walk away.

As the anonymous captain quoted in the February article, I provided those words for a few reasonsânone of which involved causing a fire for the sake of watching it burn. One, although I hadn't sought out the press, I understood their power in bringing issues to the public. Nothing made large institutions change their decisions more quickly and more emphatically than

public pressure. Two, I truly believed what I saidâI wanted us out of Iraq too, but not at the expense of the men who had served next to us for so long. It angered the fuck out of me that some public relations fobbits ostentatiously told terps that if they didn't like the ban, they could seek out alternative employment. And three, I couldn't shake Suge's voice at night, as I remembered him imploring me to allow him to keep his mask on.

public pressure. Two, I truly believed what I saidâI wanted us out of Iraq too, but not at the expense of the men who had served next to us for so long. It angered the fuck out of me that some public relations fobbits ostentatiously told terps that if they didn't like the ban, they could seek out alternative employment. And three, I couldn't shake Suge's voice at night, as I remembered him imploring me to allow him to keep his mask on.

It had occurred the previous spring, long before my days as a Gunslinger and even before I became an e-swashbuckler through the demise of my blog. While on a Sheik Nour escort mission, we drove along Route Pluto, well into the core of North Baghdad, to an Iraqi police station opening ceremony. While there, some of the Gravediggers and I wandered around, marveling at the new buildings. Obviously, a lot of rank and brass walked around too, but they all ignored us, until a colonel I didn't know pulled me aside.

“Lieutenant, is that big guy your terp?” He pointed at Suge, who unbeknownst to me, had donned his mask.

“Roger, sir, he's mine,” I replied.

The colonel spoke quietly and calmly, but with the crispness of a man who didn't enjoy dialogue. “No masks here,” he said. “At all. We're professionals, and we're trying to show the IPs that they shouldn't be afraid of their own populace. We can't damn well do that when our own terps are wearing masks, can we?”

“No, sir,” I said. “It's my fault: I gave him that discretion. I'll fix it immediately.” The colonel nodded and walked away.

I gave Suge authority to wear his mask when he chose to because it was his life, in his country, and he knew better than any of us when and where he felt safe. But I knew he understood the inanity of army rules and orders, so when I told him, rather innocently and ignorantly to “lose the mask,” his response shocked me.

“Please, Lieutenant, do not ask that of me!” Suge roared, emotion erupting out of him like lava from a volcano. “I cannot do it!”

Staff Sergeant Boondock and Doc looked over at us quizzically. Suge had never questioned any of us in a serious manner, let alone me, his known sugar daddy.

“What's wrong?” I asked.

“This place,” he said, his voice muffled by the cotton, “is very bad, Lieutenant. IPs are work with Jaish al-Mahdi, and they hunt terps. I know this to be true. We are close to my home. I must be careful.”

I nodded, understanding Suge's plight, as his fear was justified. A few years back, thirty members of the Mahdi Army armed with AKs had showed up at his construction business and requisitioned all of his assets, financial or otherwise. His smile, and quickness to accede to their demands, had saved his life. Whether I believed Suge was safe or not at the IP station was absolutely irrelevant. While I understood the colonel's points, I felt that we catered to false appearances with that approach. Suge's feeling safe enough to not don a mask at the IP station should have been our goal, not making the IPs think our terps felt safe. It felt like we took off the interpreters' masks to sport one of our own, except ours hid reality instead of a face. Nonetheless, I didn't want to risk running into that colonel again either, so I told Doc to walk Suge back to our Strykers. Staff Sergeant Boondock and I walked around for another hour or so without an interpreter, until Sheik Nour got bored with the ceremony. Then we drove him home and sat in his driveway for ten hours, keeping the hajji bogeyman away.

Other books

The Lawless West by Louis L'Amour

The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins

Plunge by Heather Stone

Red Light Specialists by Mandy M. Roth, Michelle M. Pillow

Pretend With Me (Midnight Society #1) by Jemma Grey

Vampires in Devil Town by Hixon, Wayne

THE CRY FOR FREEDOM (Winds of Betrayal) by Hines, Jerri

Betrayals of Spring by L.P. Dover

Amos's Killer Concert Caper by Gary Paulsen

Smoke Alarm by Priscilla Masters