Leonardo and the Last Supper (49 page)

Read Leonardo and the Last Supper Online

Authors: Ross King

The Turks did indeed begin raiding Venetian territory in the summer of 1499, burning villages and taking thousands of prisoners; at one point they came within twenty miles of Venice’s lagoon. But even the Gran Turco’s intervention came too late for Lodovico. At the beginning of August a French army of some thirty thousand men, commanded by Trivulzio, mustered at Asti. On the thirteenth they attacked, taking fortress after fortress, and (in a brutal reprisal of the “terror of Mordano”) massacring the garrison at Annone. On the other side of the duchy, a Venetian army crossed the eastern frontier singing, “

Ora il Moro fa la danza!

” (Now the Moor will do a dance!). Panic and disorder broke out in Milan. The homes of Sforza loyalists were attacked. Galeazzo Sanseverino’s palazzo and stables were sacked, and Lodovico’s treasurer was beaten to death in the street by a mob. A Milanese chronicler described the destruction of another nearby home, “recently built and not yet completed”: that of Il Moro’s chamberlain Mariolo de’ Guiscardi.

40

Leonardo’s sole architecture commission, it seems, went up in smoke even before it was completed.

The combination of mob violence and French steel were too much for Lodovico. On the second of September, ill with gout and asthma, he fled the city with Sanseverino and an armed escort, riding north for a refuge in Germany. First, however, he mounted his black charger and, donning a black cape, went to Santa Maria delle Grazie to kneel at the tomb of his wife.

A Venetian diarist was awed by the duke’s sudden downfall. “Only think, reader,” he wrote, “what grief and shame so great and glorious a lord, who had been held to be the wisest of monarchs and ablest of rulers, must have felt at losing so splendid a state in these few days, without a single stroke of the sword.”

41

Leonardo, like the Venetian diarist, was chastened by Lodovico’s downfall. He was also angry. His observation, scrawled on the back cover of one of his notebooks, reads bitterly: “The Duke has lost the state, property and liberty, and none of his enterprises was carried out by him.”

42

The judgment is a harsh one, but Leonardo’s bitterness is understandable. He may have witnessed the destruction of the villa he was building for Mariolo de’ Guiscardi, while an even more precious enterprise—the equestrian monument—also came to final ruin with the invasion of the French.

Leonardo seems to have spent the weeks before the fall of Il Moro in his usual way, avidly pursuing his own studies in the Corte dell’Arengo. “On the 1st of August 1499,” reads one of his notes, “I wrote here of motion and of weight.”

43

He also seems to have resumed or continued work on the equestrian monument, since another note from this period suggests that his experiments on how to cast the gigantic bronze statue were ongoing. Next to the drawing of the statue of a man in a casting mold (presumably Francesco Sforza) he wrote, “After you have finished it and let it dry, set it in a case.”

44

Leonardo may have been planning to turn part of his new property beside Santa Maria delle Grazie into a foundry where he would cast the statue and its rider. It seems likely that at some point in 1498 or 1499 he transported the giant clay model from the Corte dell’Arengo to this vineyard, a distance, as the crow flies, of almost exactly a mile.

The model for the clay horse was probably sitting in the vineyard when, on 9 September, a week after Lodovico’s flight from Milan, a vanguard of French troops entered the city through the Porta Vercellina, the gate nearest Santa Maria delle Grazie. Many years later, in 1554, a Knight Hospitaller named Sabba da Castiglione described the ensuing events. Castiglione was born in Milan about 1480 and was probably in the city to witness the invasion. More than fifty years later, he could not speak of what happened without “grief and indignation.” The equestrian model was “shamefully ruined,” he lamented, when Gascon crossbowmen used it for target practice.

45

Although Castiglione did not identify the location of the model at the time of the incident, the horse would have been especially vulnerable to the archers if it sat in the vineyard outside the Porta Vercellina.

Leonardo likewise had reason to fear for his work in Santa Maria delle Grazie. One reason why the equestrian monument provided such an irresistible target to the crossbowmen was that it was, of course, a symbol of the Sforza regime. Lodovico had wanted

The Last Supper

, like the bronze horse,

to celebrate the Sforza name. Its family crests and the portraits of prominent courtiers gave it unmistakable and perilous associations with the ousted duke. There was also the danger, as ever with the French, of casual despoliation. Their occupations of Florence in 1494 and Naples in 1495 had witnessed widespread looting. Five years later, the plundering resumed. From Pavia, twenty-seven portraits of members of the Visconti and Sforza families were stolen. In Milan, gems and marbles were looted from the Castello, and Trivulzio helped himself to Lodovico’s tapestries. The homes of Lodovico’s supporters in the quarter outside the Porta Vercellina—Leonardo’s new neighbors—were occupied by the French. The invaders also took control of the Castello, which Lodovico’s castellan treacherously surrendered in exchange for money. “In the Castello there is nothing but foulness and dirt, such as Signor Lodovico would not have allowed for the whole world!” complained a Venetian witness to the occupation. “The French captains spit upon the floor of the rooms, and the soldiers outrage women in the streets.”

46

In the Sala delle Asse, one of the four tablets celebrating Lodovico’s achievements was defaced so thoroughly it is impossible to know what it once said.

Leonardo’s

Last Supper

, following the arrival in Milan of Louis XII, barely survived this depredation. The king’s triumphal entrance to the city, wearing ducal robes, took place on 6 October. Accompanying Louis was Cesare Borgia, who wore a purple suit and paraded beneath an ermine-lined canopy held aloft by eight Milanese noblemen. Much pageantry ensued as a triumphal chariot showing Victory supported by Fortitude, Penance, and Renown passed beneath a triumphal arch surmounted by an equestrian statue of the French king. Coins were distributed bearing the legend “Louis, King of France and Duke of Milan.”

On the following day, the new duke of Milan was taken to Santa Maria delle Grazie to gaze upon the mural ordered by his predecessor. Evidently the painting’s fame had preceded it. Louis generally had scant interest in paintings unless they depicted him, preferably on horseback. He was, however, suitably impressed by Leonardo’s handiwork. He even hoped to pay it the ultimate French compliment: he wanted to loot it. According to Paolo Giovio, the king “coveted it so much that he inquired anxiously from those standing around him whether it could be detached from the wall and transported forthwith to France.” He desisted in this endeavor only when informed that the removal of the painting “would have destroyed the famous refectory.”

47

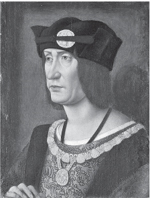

King Louis XII of France

Vasari expanded the story, claiming the king went so far as to engage architects to make cross-stays of wood and iron so the painting could be taken to France. Louis proceeded, he claimed, “without any regard for expense, so great was his desire to have it.”

48

The king’s failure to expropriate Leonardo’s work marked a rare victory for the Milanese.

Lodovico Sforza’s flight from Milan deprived Leonardo of his patron of the previous sixteen years. His harsh assessment of the duke, that “none of his enterprises was carried out,” reveals his frustration at what he regarded as wasted opportunities, not least those that concerned himself. Yet if Il Moro arguably undervalued and underused his painter and engineer, primarily employing him as a theatrical impresario, interior decorator, and general handyman, he had at least offered Leonardo creative latitude and financial security. For the better part of two decades, Leonardo had been allowed to pursue his intellectually itinerant trail through aeronautics, anatomy, architecture, mathematics, and mechanics.

With Lodovico ousted, Leonardo suddenly needed to find a new patron. He was quite prepared to offer his services to the enemy, remaining in Milan despite the disorder. No document records that he was present when Louis XII visited Santa Maria delle Grazie, but presumably the king would

have wished to meet the artist whose work he so admired. Leonardo, for his part, may have wished to follow in the footsteps of the sculptor Guido Mazzoni, whose work in Naples so impressed Charles VIII in 1495 that he was invited to take up a well-paid job at the French court.

Leonardo did find at least one patron. At some point his services were secured by the powerful secretary to Louis XII, Florimond Robertet, whose Italian-style château in the Loire Valley would soon host one of the great private art collections of the sixteenth century, including a (now-lost) bronze

David

by Michelangelo. Robertet commissioned Leonardo to paint what became the

Madonna of the Yarnwinder

, a small Madonna and Child painting that showed (as a witness who saw the work later recorded) “a Madonna sitting as if she wished to wind yarns onto a distaff” while the Christ Child, feet in a basket of yarn, holds the cross-shaped object, “not willing to yield it to his mother, who appears to want to take it from him.”

49

Apart from Robertet, Leonardo made another contact in Louis XII’s entourage: “Get from Gian de Paris the method of painting in tempera,” reads one of his notes.

50

Gian de Paris was the court painter and royal

valet de chambre

Jean Perréal—Leonardo’s opposite number, so to speak, at the French court. Leonardo probably first met him in 1494 when Perréal accompanied Charles VIII to Milan. The pair shared an interest in, among other things, astronomy. “The measurement of the sun, promised me by Maestro Giovanni, the Frenchman,” reads another of Leonardo’s notes.

51

In 1499, Perréal returned to Milan in the entourage of Louis XII. As

peintre du roi

, he was probably the man responsible for overseeing the decorations and festivities surrounding Louis’s triumphant entrance into the city. He may also have been the one who guided the king’s footsteps to Santa Maria delle Grazie.

Leonardo hoped for yet another contact among the invaders. Toward the end of 1499 he began planning his departure from Milan: a permanent move, it appears. “Sell what you cannot take with you,” he wrote in a memorandum composed on a page that included an architectural drawing done a decade earlier.

52

The memo listed the possessions he planned to take: bed linen, shoes, handkerchiefs and towels, a book on perspective, another on geometry, four pairs of hose and a jerkin, even some seeds, all packed into “two covered boxes to be carried on mules.” A third box would be taken by the muleteer for safekeeping to Vinci, where an uncle still lived.