Leonardo and the Last Supper (53 page)

Read Leonardo and the Last Supper Online

Authors: Ross King

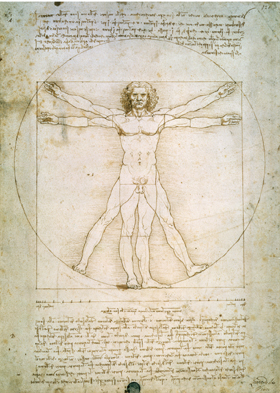

Leonardo da Vinci,

Vitruvian Man

, c. 1490

Andy Warhol,

The Last Supper

, 1986

My thanks to everyone who provided me with material assistance and/or moral support as I researched and wrote. It was a pleasure and a learning experience, as always, to work with my editor in New York, George Gibson, whose patient, tactful, and astute queries made the book much better than it would otherwise have been. My other profound debt is to Martin Kemp, Emeritus Professor of the History of Art at Oxford University, who was extremely generous with both his time and his resources. He read the manuscript, answered various questions, and gave me access to the treasures of his Leonardo collection in the History Faculty Research Hall at Oxford University.

Several other people also read the book in manuscript form and offered comments and advice. My friend Dr. Mark Asquith proved, as ever, an alert and probing reader. Another friend, Tom Smart, likewise read the manuscript and gave counsel and encouragement, as did my faithful literary agent, Christopher Sinclair-Stevenson. Dava Sobel, Keith Devlin, and my brother, Dr. Bryan King, kindly responded to my questions about areas of Leonardo’s expertise that go well beyond my own. Dr. Matthew Landrus generously permitted me to use his perpective drawing of

The Last Supper

. Nathaniel Knaebel at Bloomsbury efficiently handled the transformation of manuscript into book, and I thank Paula Cooper for her excellent and attentive copyediting. Lea Beresford tracked down the images used in the book and provided other valuable logistical support. My thanks, too, to Bill Swainson and everyone at Bloomsbury in London.

My indebtedness to Leonardo scholars is, I hope, adequately reflected in my notes and bibliography. I have been the beneficiary of the researches, writings, and insights of (to name only a few of the most prominent) Kenneth Clark, Martin Kemp, Charles Nicholl, and Carlo Pedretti. As well,

one of the pleasures of researching my book was reading Leonardo’s own words—and glimpsing the frenetic stirrings of his marvelously inventive, magpie mind—in the edition of the notebooks first compiled and translated in 1883 by Jean-Paul Richter. For these and other volumes I am grateful to have had access both to the London Library and to Oxford University’s Sackler Library.

Finally, thank you as always to my wife, Melanie, for her love, support, and patience during my Leonardo years. This book is dedicated to her father, Bunny Harris, on the occasion of his eightieth birthday. He has long been a reliable source of conversation and good-natured moral support—to say nothing of unstinting food and drink—to both of us.

Chapter 1

1

Francesco Guicciardini,

The History of Italy

, trans. Sidney Alexander (New York: Macmillan, 1969), 32.

2

Ibid., 49.

3

Quoted in Julia Cartwright,

Beatrice d’Este, Duchess of Milan, 1475–1497: A Study of the Renaissance

(London: J. M. Dent & Sons, 1910), 314.

4

Philip de Commines,

The Memoirs of Philip de Commines, Lord of Argenton

, vol. 2, ed. Andrew R. Scoble (London: Henry G. Bohn, 1856), 151.

5

Quoted in Cartwright,

Beatrice d’Este

, 223.

6

Commines,

Memoirs

, vol. 2, 107–8.

7

Edoardo Villata, ed.,

Leonardo da Vinci: I documenti e le testimonianze contemporanee

(Milan: Castello Sforzesco, 1999), 76.

8

Evelyn Welch, “Patrons, Artists and Audiences in Renaissance Milan,” in Charles M. Rosenberg, ed.,

The Northern Court Cities: Milan, Parma, Piacenza, Mantua, Ferrara

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 46.

9

Villata,

Documenti

, 77.

10

Giorgio Vasari,

Lives of the Artists

, vol. 1, trans. George Bull (London: Penguin, 1965), 255; Kate T. Steinitz and Ebria Feinblatt, trans. “Leonardo da Vinci by the Anonimo Gaddiano,” in Ludwig Goldscheider,

Leonardo da Vinci: Life and Work, Paintings and Drawings

(London: Phaidon, 1959), 32; Lomazzo, quoted in Carlo Pedretti,

Leonardo: Studies for

“The Last Supper”

from the Royal Library at Windsor Castle

(Florence: Electa, 1983), 134.

11

For the horseshoe: Vasari,

Lives of the Artists

, 270; for the mountaineering: vol. 2, Jean-Paul Richter, comp. and ed.,

The Literary Works of Leonardo da Vinci

, 2 vols., (London: Phaidon, 1970), §1030.

12

Martin Kemp,

Leonardo da Vinci: The Marvellous Works of Nature and Man

(Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 160.

13

Richter, ed.,

The Literary Works

, vol. 2, §1018.

14

Ibid., vol. 2, §1340.

15

Niccolò Machiavelli,

The Prince

, trans. George Bull (London: Penguin, 1961), 21; and Christopher Lynch, ed. and trans.,

The Art of War

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 1, 62.

16

Laura F. Banfield and Harvey C. Manfield, trans.,

Florentine Histories

(Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1990), 313.

17

Villata, ed.,

Documenti

, 44.

18

Richter, ed.,

The Literary Works

, vol. 2, §1363.

19

Steinitz and Feinblatt, trans., “Leonardo da Vinci by the Anonimo Gaddiano,” in Goldscheider,

Leonardo da Vinci

, 30.

20

See Caroline Elam, “Art and Diplomacy in Renaissance Florence,”

Journal of the Royal Society of Arts

136 (October 1988): 813–20.

21

Villata, ed.,

Documenti

, 45.

22

Richter, ed.

The Literary Works

, vol. 2, §1384.

23

Steinitz and Feinblatt, trans., “Leonardo da Vinci by the Anonimo Gaddiano,” in Goldscheider,

Leonardo da Vinci

, 31.

24

Richter, ed.

The Literary Works

, vol. 2, §§1190 and 796.

25

Villata, ed.,

Documenti

, 44.

26

Ibid., 45–46.

27

Ibid., 46.

28

Ibid., 57–61.

29

Richter, ed.,

The Literary Works,

vol. 2, §720.

30

Villata, ed.,

Documenti

, 62–63.

31

Ibid., 78–79. The first poem, by Baldassare Taccone, states that Leonardo is still working on the clay horse, so the model was not finished, much less publicly exhibited, in 1493.

32

Jean-Paul Richter, ed.,

The Literary Works of Leonardo da Vinci

, with a commentary by Carlo Pedretti, 2 vols. (Oxford: Phaidon Press, 1977), vol. 1, 9. Hereafter referred to as

Commentary

.

33

Richter, ed.,

The Literary Works

, vol. 2, §§710, 711.

34

Ibid., vol. 2, §714.

35

Commines,

Memoirs

, vol. 2, 125.

36

Quoted in Cartwright,

Beatrice d’Este

, 256.

37

Commines,

Memoirs

, vol. 2, 133.

38

Luca Landucci,

A Florentine Diary from 1450 to 1516

, Alice de Rosen Jarvis, trans. (London: J. M. Dent, 1927), 22.

39

Richter, ed.,

The Literary Works

, vol. 2, §1340.

40

Banfield and Manfield, trans.,

Florentine Histories

, 309.

41

Bartolomeo Cerretani,

Storia fiorentina

, ed. Giuliana Berti (Florence: Leo S. Olschki, 1994), 201.

42

Pietro Bembo,

History of Venice

, ed. and trans. Robert W. Ulery Jr. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007), 81.

43

Guicciardini,

The History of Italy

, 54.

44

Quoted in Cartwright,

Beatrice d’Este

, 231.

45

Villata, ed.,

Documenti

, 85.

46

Thomas Tuohy,

Herculean Ferrara: Ercole d’Este (1471–1505) and the Invention of a Ducal Capital

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 97.

47

Richter, ed.,

The Literary Works

, vol. 2, §1514.

Chapter 2

1

Stenitz and Feinblatt, trans., “Leonardo da Vinci by the Anonimo Gaddiano,” in Goldscheider, 31.

2

Quoted in Janice Shell and Grazioso Sironi, “Cecilia Gallerani: Leonardo’s

Lady with an Ermine

,”

Artibus et historiae

13 (1992): 48; and Carlo Pedretti,

Leonardo: Architect

, trans. Sue Brill (London: Thames and Hudson, 1986), 77.

3

For a discussion of this story, see Alexander Nagel, “Structural Indeterminacy in Early Sixteenth-Century Italian Painting,” in Alexander Nagel and Lorenzo Pericolo, eds.,

Subject as Aporia in Early Modern Art

(Farnham, Hants.: Ashgate, 2010), 17–23.

4

Christiane Klapische-Zuber states that life expectancy in Renaissance Italy was “between twenty and forty years.” See Lydia Cochrane, trans.,

Women, Family and Ritual in Renaissance Italy

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985), 57, n45.

5

Richter, comp. and ed.,

The Literary Works

, vol. 2, §1346.

6

Ibid., vol. 2, §§1365, 1366. Leonardo’s friend, the poet Antonio Cammelli, is quoted in Charles Nicholl,

Leonardo da Vinci: The Flights of the Mind

(London: Allen Lane, 2004), 160.

7

Paolo Giovio, “The Life of Leonardo da Vinci,” in Goldscheider,

Leonardo da Vinci

, 29.

8

Villata, ed.,

Documenti

, 3. For the discussion of the tradition that assigns the farmhouse in Anchiano as Leonardo’s birthplace, see Nicholl,

Flights of the Mind

, 18–19.

9

Villata, ed.,

Documenti

, 102 and 87; Richter, ed.,

The Literary Works

, vol. 2, §722.

10

Quoted in Iris Origo, “The Domestic Enemy: The Eastern Slaves in Tuscany in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries,” in

Speculum: A Journal of Medieval Studies

30 (July 1955): 321. Origo reports (p. 325) that domestic slaves were common in the villages and towns outside Florence. For the price of slaves, see Richard A. Goldthwaite,

The Economy of Renaissance Florence

(Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press), 377. On the possibility that Leonardo’s mother was a slave, see Francesco Cianchi,

La madre di Leonardo era una schiava? Ipotesi di studio di Renzo Cianchi

(Vinci: Museo Ideale Leonardo da Vinci, 2008).

11

See Malcolm Moore, “Leonardo Da Vinci may have been an Arab,”

Telegraph

, 7 December 2007; and the report by Marta Falconi:

www.msnbc.msn.com/id/15993133/ns/technology_and_science-science/t/experts-reconstruct-leonardo-fingerprint/#.TwGqXRzCcrg

.