Leonardo and the Last Supper (52 page)

Read Leonardo and the Last Supper Online

Authors: Ross King

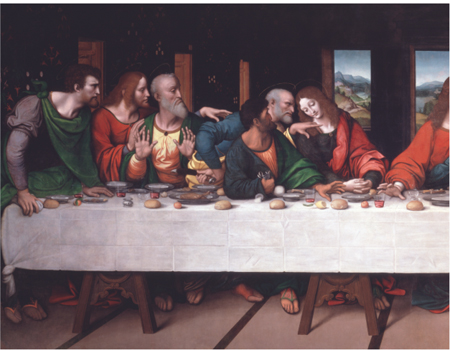

The ruins of the refectory at Santa Maria delle Grazie after an RAF bomb during WWII miraculously spared

The Last Supper

Some critics have argued that

The Last Supper

is now 80 percent by the restorers and 20 percent by Leonardo.

34

The mural’s restoration has become a puzzle of spatiotemporal continuity to match that of the ship of Theseus, the vessel carefully preserved by the Athenians, who eventually replaced every one of its rotting timbers and thereby caused philosophical disputes about whether or not it was still the same ship. What one sees after waiting in line today and then walking over dust-absorbing carpets and through a pollutant-sucking filtration chamber before entering the refectory for fifteen minutes of fame is a far cry, admittedly, from what Leonardo originally unveiled. However, the conservators’ efforts in stabilizing the painting and returning it to its original condition—as far as is humanly and technologically possible—were highly sensitive. We now know infinitely more about Leonardo’s technique (particularly his use of oils) and are better able to appreciate his virtuoso abilities: the transparency of the glasses, the plates of food, the ironed pleats of the tablecloth. More important, the faces of the apostles (which the restorers based, where possible, on Leonardo’s drawings) are no doubt closer to Leonardo’s original intentions, especially that of Judas, who is no longer the caricature of evil beloved of earlier restorers.

The restorers were assisted in their task by the many early copies of the painting that revealed details lost or damaged in the original: Judas’s money bag, the overturned saltcellar, the expressions of the apostles, the colors of the robes. Most faithful is the large-scale oil on canvas version painted in about 1520 by Giampietrino, possibly for one of Lodovico Sforza’s sons. Giampietrino seems to have worked with Leonardo in the 1490s, giving him impeccable credentials as an interpreter: he might even have assisted the master in the refectory. In 1987, his twenty-five-foot-wide canvas was sent from Oxford to Milan to aid with the restoration.

Giampietrino’s was only one of numerous versions. Such was the fame of

The Last Supper

that a demand grew for reproductions almost before the paint had dried. Churches, monasteries, hospitals, cardinals, princes: everyone

wanted a copy, rather in the way that everyone wanted a relic of the True Cross or the finger bone of a saint.

The Last Supper

was engraved as early as 1498 by an unknown artist, and in the decades after its completion versions were done in fresco, panel, canvas, marble, terra-cotta, tapestry, and painted wood. Copies were produced in places as widely scattered as Venice, Antwerp, and Paris. The Certosa di Pavia even had two versions, one done in oils and another in marble.

These copies were the first artifacts in an industry that today encompasses everything from postcards and giclée prints to the seven versions found by Umberto Eco on the road between Los Angeles and San Francisco, all done in wax. Today you can get a

Last Supper

tattooed across your chest, or be buried in a coffin with Leonardo’s scene carved on both sides. You can see a zoomable sixteen-billion-pixel version on your home computer, an online visualization that its creators, Haltadefinizione, claim to be “the highest definition photograph ever in the world.” Even greater visual pyrotechnics were unveiled in 2010, when the British filmmaker Peter Greenaway created a multimedia installation at New York’s Park Avenue Armory, complete with a life-sized “clone” not only of

The Last Supper

(produced by a inkjet printer) but of the entire refectory itself. Even copies of

The Last Supper

generate copies: Andy Warhol’s silk screens were inspired not so much by Leonardo’s painting itself (Warhol was unable to see the mural when he began work in 1985–86 due to the ongoing conservation) as by a whole range of copies: a famous nineteenth-century engraving by Raphael Morghen, children’s books, religious kitsch, and no doubt also the version that hung in the kitchen of his family home in Pittsburgh.

35

The Last Supper

is arguably the most famous painting in the world, its only serious rival Leonardo’s other masterpiece, the

Mona Lisa

. But the painting’s tremendous fame is detached from what we see before us in the refectory. The world’s most famous painting, an Athenian philosopher could argue, no longer exists. But this ghostly evanescence has only enhanced its fame, making it available for endless interpretations and reinventions. Not only does it tell a story from the Gospels: it has become its own story, one of Leonardo’s miraculous triumph followed by centuries of decline, loss and—finally, five hundred years later—a kind of resurrection. Leonardo, perhaps, was right: what is fair in art does not entirely pass away.

Leonardo da Vinci,

The Virgin of the Rocks

(Louvre version), 1483–c.1485

Giovanni Pietro Rizzoli, later known as Giampietrino, copy of Leonardo’s

The Last Supper

, c. 1520. This copy of the mural by Leonardo’s former apprentice is among the most faithful ever produced

Map of Milan from George Braun and Frans Hogenburg’s

Civitates Orbis Terrarum

, showing the Castello Sforzesco at the top

Leonardo da Vinci, detail of Christ in

The Last Supper

Giovanni Donato da Montorfano,

Crucifixion

, refectory of Santa Maria delle Grazie, 1495

Leonardo da Vinci,

Portrait of Cecilia Gallerani

(

Lady with an Ermine

), c. 1489