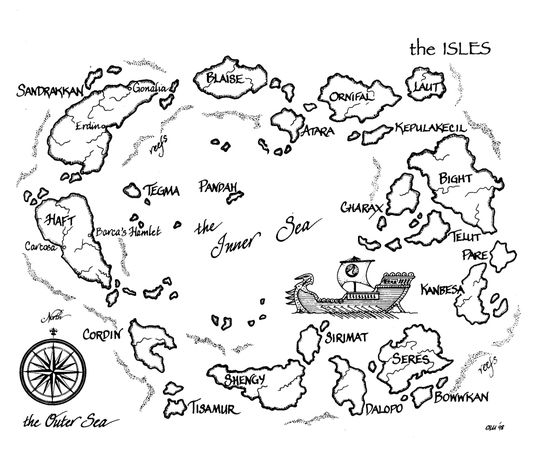

Lord of the Isles (67 page)

Authors: David Drake

The centipede came on, its feet clicking like hail on the mill's slate roof. Ilna didn't look over her shoulder. What would be, would be. She remembered every detail of what she'd done in Erdin. Her only regret was that Garric would die also. The fault was hers alone, but this wasn't a pattern of her weaving.

The old woman's heels no longer climbed at the level of Ilna's eyes. A moment later Ilna fell forward because the handhold she'd reached for by habit wasn't there to take her weight. She sprawled on a plain as flat as a millstone, featureless except for a black throne looming like an island in a calm sea.

Garric collapsed beside her. They'd escaped the centipede. There was no sound but their breath and their hearts pounding.

“The Throne of Malkar,” Garric whispered.

“Yes,” said Tenoctris. There was no other sound in this world.

Ilna got her limbs under her and rested her forehead against the ground. The surface had no temperature or texture; its gray hue was a perfect neutral, neither color nor absence of color. It was the palpable form of the limbo in which she had lost her soul.

The three of them were in a vast circle of sourceless light whose center was the black throne. The walls of darkness were moving in.

“Come,” Garric said. He stood up.

“Garric, no,” Ilna wheezed. She was crying with anger

and frustration; and fear, she recognized the fear. “It's better to die. Garric, I know what lives here.”

and frustration; and fear, she recognized the fear. “It's better to die. Garric, I know what lives here.”

Tenoctris was rising. “Come,” Garric repeated, and touched Ilna's cheek with his hand. She got up, blind with tears but unwilling to deny his command.

They walked toward the throne. Garric was between the two women, a hand on either of them. The wall of darkness squeezed closer behind them, though the distance to the throne didn't seem to change.

Ilna bent forward to look at the other woman. “Tenoctris?” she said.

“This is the only path,” Tenoctris said. “I don't know whether it's a path out.”

“We started this,” Garric said. “We're going to finish it.”

Darkness brushed close at their heels; driving them, threatening to engulf them if they hesitated. Ilna felt the damned moaning in stark despair, utter and eternal.

Their

eternity if they let the darkness swallow them, hers and Garric's and the old woman's.

Their

eternity if they let the darkness swallow them, hers and Garric's and the old woman's.

That bleak eternity would be preferable to joining the thing that was the throne.

“Malkar isn't a person,” Tenoctris said. Her voice was audible but oddly flat: there were no echoes in this place, not even from the ground. “Malkar simply is. The throne exists only as a symbol.”

Tenoctris might have been talking to either of them or to herself, marshaling her thoughts here at the end. Tenoctris had lived for her learning, Ilna knew.

What had Ilna os-Kenset lived for? Well, she'd helped defeat the Hooded One. That was at least a result of her existence if not a purpose.

She chuckled. Garric squeezed her hand in comradeship. Did he understand, even now? Well, that didn't matter either.

“To sit on the Throne of Malkar is to be the focus of half the power in the cosmos,” Tenoctris said. “To have half the power in the cosmos. A man with that power could do anything.”

“But he wouldn't be a man,” Ilna said.

“No,” Tenoctris said. “He wouldn't be a man.”

Ilna could see details of the throne now, though when she focused on any particular point it blurred away. It was like trying to watch serpents mate in the twilight. The patterns were too complex for even Ilna to grasp fully, but she understood them well enough.

She had been part of the pattern not long ago. The tree she'd surrendered to somewhere in gray limbo was a tiny part of the throne's vast fabric.

“To sit on the Throne of Malkar,” Ilna said with a detached smile, “is to become all evil.”

“In human terms,” said Tenoctris. “In human terms, yes.”

They were very close. The throne stood on a three-step platform. It had broad arms and a high back formed of the same material. It was sized for a manâa tall man, a man like Garricâbut at the same time Ilna felt its vastness spread through all the darkness of this plain and of the greater universe beyond.

Garric gathered the two women into the cradle of his arms, one in the crook of either elbow. He lifted them and walked forward.

No, but Ilna's mouth didn't speak the denial her mind had formed. If this was what it was to beâ

Garric mounted the platform's three steps, moving with the steady grace that had marked him from childhood. He disregarded the weight of the women he carried. He was smiling faintly.

“All the power ⦔ Tenoctris whispered.

So be it!

Instead of sitting, Garric stepped onto the throne's seat. He lurched up with his burdens and put his left foot on the carven arm as the next step. Then he leaped as though he wasn't exhausted, as though he wasn't carrying two women who for their different reasons would have been unable to come this far without his strength.

Garric's right foot gained the top of the throne's back. He

rose once more on the power of that leg alone and hurled all three of them up into the darkness.

rose once more on the power of that leg alone and hurled all three of them up into the darkness.

Arms caught them. The light of paper lanterns was dazzling, and the twilight glow around the door baffles was like the sun at noon.

They were in a room Ilna didn't recognize, though she saw that the furnishings were Serian. Garric was in the arms of Cashel, whose blank expression showed fear for his friend's utter collapse. Sharina held Tenoctris; the girl was reaching for a cup of juice to offer the old woman.

“Here, let me lay you down,” Liane said. “It's all right, Ilna. You're safe now.”

G

arric lay with his eyes closed, savoring the fact that he had no responsibilities whatever for the moment. Tiny hands smeared ointment on his scrapes and shallow cuts; as before, the Serian healers chattered birdlike. The only injury that really hurt was the bruise over his ribs, and he wasn't even sure how he'd gotten that one.

arric lay with his eyes closed, savoring the fact that he had no responsibilities whatever for the moment. Tiny hands smeared ointment on his scrapes and shallow cuts; as before, the Serian healers chattered birdlike. The only injury that really hurt was the bruise over his ribs, and he wasn't even sure how he'd gotten that one.

But he was tired. He was so very tired.

“Thanks for bringing Ilna back,” Cashel said. “I wish I could've helped, but I guess you didn't need me.”

Garric tried to laugh. He shouldn't have: it felt like a handful of knives stabbing into his lower rib cage. When he managed to stop gasping he wheezed, “A lot of it was Ilna bringing us. We wouldn't have done it without her.”

“He had to carry me most of the way,” Ilna said in a thin voice from nearby to Garric's left. She wasn't a person Garric, imagined would ever break, but she must have been worn very close to vanishing, like a knife sharpened too often. “But the Hooded One is dead.”

Garric opened his eyes and sat up. The Serian child chided him in words he couldn't understand and would have ignored in any case. “That's true isn't it, Tenoctris? The Hooded One is dead.”

A dozen lanterns hung around the walls of the room, the light of each throwing its lamp's shadow onto the paper shade. A brazier heated medicines in porcelain bowls under observation by the old Serian woman, while the male healer painted styptic on Tenoctris' scratched thigh.

Liane was massaging Ilna, whose muscles looked as flaccid as warm wax.

Worn very close to vanishing â¦

Worn very close to vanishing â¦

Tenoctris sat up. She managed a smile, though the lines around her eyes tightened every time the healer's brush touched her.

“I thought the same thing a thousand years ago, you'll recall,” she said. “Perhaps it's true this time, but I'm afraid that doesn't really matter.”

“It matters to me,” Sharina said. She spoke quietly, but her voice had no more mercy in it than an axeblade does. She sat near Cashel, her hands crossed in her lap over the hilt of the Pewle knife.

“Yes,” said Tenoctris, nodding with her former quiet authority. “To all of us. And to the Hooded One himself for the considerable length of time it took him to fall. But he was only part of the problem.”

Ilna looked up at Garric. She smiled, a disconcertingly cold expression.

“The tree wasn't the Throne of Malkar,” she said, a reference that only Tenoctris among the other people in the room might understand. “But it was too much for me. I was weak.”

“No,” said Tenoctris. “It was your strength, not your weakness, that made you vulnerable. But your point is correct: the Hooded One was the human agent of an impersonal force. The force will work through others as it worked through him, and through what you call the tree. Malkar waxes and wanes. Malkar is rising now, just as it did a thousand

years ago. If it continues, it will smash the Isles back into barbarism.”

years ago. If it continues, it will smash the Isles back into barbarism.”

“Not this time,” Garric said. He hugged himself, trembling with emotions and memories that were only partly his own. “Not this time!”

Garric thought he felt at the core of his soul the king laughing. “Not this time, lad!” he heard as if in a dream. “Not this time, King Garric!”

S

he stared at the tourmaline pieces scattered across the game board in a pattern she could not yet understand.

he stared at the tourmaline pieces scattered across the game board in a pattern she could not yet understand.

Her hooded opponent was dead, but she had not defeated him and she did not know who had. There were other players, other wizards to whom the cosmos was only a game, playing against her. She was as certain of that as she had been when she denied the possibility only a few months before.

She would identify and defeat her new opponents. She would sit on the Throne of Malkar and crush the cosmos in her hand like a ripe peach if it suited her mood to do so. She alone!

She strode to the door and opened it. The servitor bowed to her, as always impassive.

“I'm not to be disturbed for any reason,” she said curtly.

“An agent from Erdin has arrived,” the servitor said. “He waits in the private interview room.”

“For any reason!” she said. She raised a hand as if to launch lightning from the bare palm.

“Yes, milady queen,” said the servitor. He bowed. His face was calm but there were minute droplets of sweat on his forehead.

The door panel was too heavy to slam. She closed it with a measured thump, then returned to the game board.

Sometimes ⦠sometimes when she rose from a sleep where nightmare had been her closest companion, the thought lingered in her mind that the pieces might sometimes play themselvesâand woe betide the wizard who tried to interfere with them.

The Queen of the Isles scowled and seated herself before the agate board. The chips of tourmaline were pawns, no more. Any other thought was madness.

She

would

set them to her will.

would

set them to her will.

I've stolen all the verse quoted within this novel from Greek and Latin poets. Celondre is Horace, whose

Odes

I carried through Basic Training and into Vietnam. Rigal is Homer, and the passage quotedâto me, the most moving passage in literatureâis from the

Iliad.

Etter is Hildebert of Lavardin; there's more to Medieval Latin than hymns and drinking songs, though I'll admit I found Hildebert a pleasant surprise.

Odes

I carried through Basic Training and into Vietnam. Rigal is Homer, and the passage quotedâto me, the most moving passage in literatureâis from the

Iliad.

Etter is Hildebert of Lavardin; there's more to Medieval Latin than hymns and drinking songs, though I'll admit I found Hildebert a pleasant surprise.

No translation does justice to its original. Theseâmineâdon't purport to do so.

The general religion of the Isles is based on Sumerian beliefs (and to a lesser degree, Sumerian practice). I have very roughly paraphrased the funeral service described herein from verses to the Goddess Inanna.

I think I should mention one thing more. The magical phrases (

voces mysticae

) quoted throughout the novel are real. I don't mean that they really summon magical powers; personally I don't believe that they do. But very many men and women

did

believe in the power of these words and used them in all seriousness to work for good or ill.

voces mysticae

) quoted throughout the novel are real. I don't mean that they really summon magical powers; personally I don't believe that they do. But very many men and women

did

believe in the power of these words and used them in all seriousness to work for good or ill.

Individuals can make their own decisions on the matter, but I didn't pronounce any of the

voces mysticae

while I was writing

Lord of the Isles.

voces mysticae

while I was writing

Lord of the Isles.

Â

âDave Drake

Chatham County, NC

Chatham County, NC

Other books

The Deputy - Edge Series 2 by Gilman, George G.

Forest of Illusions (The Broken Prism) by V. St. Clair

ONE SMALL VICTORY by Maryann Miller

The Borgias by G.J. Meyer

Rayne's Return (Hearts of ICARUS Book 3) by Laura Jo Phillips

[Roger the Chapman 06] - The Wicked Winter by Kate Sedley

Tastes Like Fear (D.I. Marnie Rome 3) by Sarah Hilary

Miedo y asco en Las Vegas by Hunter S. Thompson

Unknown by Unknown