Man With a Pan (23 page)

Then there was Chinese food. When I was six and seven and eight, I went with my family to the now-vanished emporiums of Chinese elegance on the Upper West Side, with their red lanterns, their jacketed waiters in bow ties, the dramatic silver domes that covered each dish until it was put down next to the table and unveiled. Paul Auster named a novel,

Moon Palace,

after one of these establishments, which survived into the early nineties, up near Columbia. They’re all gone now. You can still divine a tiny hint of that atmosphere at Shun Lee on Sixty-fifth Street, if you can get past the lacquered glamour to that sense of ceremony with which the meal unfolds.

I have fuzzy memories of my enthusiasms before my dad died—mayonnaise, fluffier stuff, Chinese food—and almost no memory of anything else.

My dad died just before I turned ten, and after that, the meals my mother prepared begin to come into view. Wiener schnitzel, which surely was a staple of the Dad years. Then there was ground beef and rice with ketchup, a meal I love to this day. And a favorite of mine—pork with pineapple sauce, which, in effect if not intent, had faintly Oriental overtones. My mother was a real cook, she had a feel for food, for flavor, but she was also a woman of her time. Things were fried in the pan, lightly breaded. Her great inspiration, when it came to food, usually involved dessert. She would prepare multiple bowls of some delicacy—pomegranates, or a banana crème pudding—which I would then devastate on multiple trips to the refrigerator over the period of a single night.

For a number of years into my adolescence I was fat. The most vivid sensation I had surrounding food did not involve desserts or dinners but rather the surreptitious imbibing that took place in the afternoons, when I returned to an empty apartment. I would on many occasions pour Nestlé’s Quik chocolate milk mix directly into my mouth. Sometimes I did this with confectioners’ sugar. And once or twice, when there was nothing else, I ate flour. These moments of choking gluttony are embarrassing for me to consider, but I also have to acknowledge that they are an important part of my autobiography of food, and cooking, and eating. They were the moments when fear (of what, I can’t say for sure, though in hindsight the emptiness of the apartment seems a prime candidate) most visibly asserted itself in the pattern of my eating.

7.

My wife doesn’t like to cook. I knew this from the beginning. She was forthcoming about it. On one of my first visits to her apartment she pointed to the small stove in her kitchen and said, “I use it to store sweaters.” Apparently Con Ed had called at some point, having noticed that she never used any gas, and suggested that she turn the gas off entirely. She accepted the offer. When I met her she seemed to be living on string cheese and white wine, as far as I could tell. I didn’t mind that she couldn’t cook. The list of what she could do was so much longer and more important. It seemed like a small sacrifice.

To our marriage I brought a huge enthusiasm for food that encompassed joy in the abundance and life force of the raw materials and it the rituals of eating, the pleasure of white linen. The middle step, between the perusal of the luscious vegetables, the bloody truth of the butcher, the gaping fish laid on ice, on one hand, and the table brimming with candles and plates and huge platters, on the other, was not my forte. The middle step being the actual cooking.

I never had the presence of mind to prepare for it in advance. There is something in me that values the improvised and feels the best way to achieve it is to back yourself into a corner of necessity, even to the point of panic, at which point there is hardly time for thought, just action, gesture, movement.

8.

I started to cook just at the time when the pace of things started to speed up. How is it that a small child both makes every second seem like an eternity and makes the days and weeks vanish in a blink? I started cooking when I couldn’t order out. But the reason for relishing the task surely has to do with a wish to grasp at that Salteresque slowing of time, the wish to hold moments, to feel the stopped time of the family gathered around a table, just before we begin to eat.

For dinner, we arrange ourselves at a big table, surrounded by book-shelves. I like the ceremony. My wife has mixed feelings. It took her a while to acknowledge some resistance to the idea, perhaps because she has some less-than-joyful memories of family dinners.

For my part, as the father, I rather like the slight aura of tyranny that comes with demanding that everyone sit down at once. My wife, on the other hand, likes the ceremony of lunch, which she has with our daughter every day. She prepares it and puts it on the low white table in the playroom, two plates of sandwiches covered with two paper towels. I find these covered plates poignant in their furtive anticipation of being discovered.

We now live for most of each year in New Orleans, a city where food is a religion and all sorts of food is available in restaurants everywhere. We go out, much less frequently take out, but mostly still cook at home, for reasons both spiritual and financial. I have made concessions to planning. And now my wife often cooks. The sheer tidal force of motherhood brought her to the stove. The word

feast

always seems to lead to the word

famine,

and with a kid there is no room for these bipolar culinary swings. I like that she is now a cooking partner, and I don’t. I am glad for a break, but I am not crazy about her preference for creamy, buttery French food. I am always striving for a vaguely Asian style, dousing things in teriyaki sauce and sprinkling cilantro everywhere. (When the

New York Times

ran an article explaining that a vocal minority, to which my wife belongs, hated cilantro, she sent it to me, vindicated, and for a while regularly quoted its remark that some people viscerally associate its smell with that of insects, until I demanded she stop.)

New Orleans was not a place I ever pined for or even thought much about, but now that I have landed here, I am starting to like it a lot. Even the food, heavy, often fried, is starting to work its way into my desirous palate—the emphasis on seafood, gumbo, blackened fish,

cochon de lait,

the sweet, vinegary hotness of Crystal sauce, and that most acquired taste, boiled crawfish. A wonderful perk, for me, is the city’s Vietnamese community and the attendant Vietnamese restaurants of the West Bank.

We have a grill, of course. When I cook, I try to get a white linen tablecloth on the table and light candles. We always eat dinner with our daughter. We’ve raised her very socially. In those crazed, incredible months in Roanoke after she was born, I continued to make wildly ambitious meals and serve them very late. She ate with us then, too. When she became somewhat sentient, at four or five months, we were back in New York for the summer and often took her to restaurants, stayed out late. Once, I looked at my wife as we sat eating at a café in the East Village—not our usual spot—around ten thirty at night, our daughter’s legs dangling out of the stroller, her eyes open, taking in the scene and the food.

“What are we doing here?” I said, laughing.

“I don’t know,” my wife said. “But she seems to like it.”

Flowers, white linen, candelabra, food on large serving plates—I’m transmitting not just food to my daughter in these moments but something else, something almost feminine, something attached to history, to my own mother, and in turn to her mother, who grew up in Germany, oblivious in the way of all well-off German Jews to what was coming. To this grandmother I trace whatever flair I possess in the realm of presentation. The delicacy and ornateness of things. The feeling of gemütlichkeit. The desire to savor, to hold on to, a moment.

When I cook, my daughter likes to sit near me on the counter and participate somehow. Often I let her hold the fork or knife and I put my hand over hers and we do things together that way. Or I hold her hand over the spatula and we both flip the piece of chicken. Or I put my hand over hers and we both stir the pot with a wooden spoon.

I think about what I will pass on to my daughter. The tablecloth, the ceremony, the three of us sitting together for a meal. Or the late-night forays into the kitchen when everyone else in the house is asleep and I am again, as in those teenage afternoons, alone in the house, a kind of narcotic, floating feeling coming over me as I open the refrigerator door yet again to see what is inside.

Recipe File

Grilled Redfish

1 pound redfish

Hoisin sauce

Red and yellow cherry tomatoes

Scallions

Cilantro, to taste

Eden Shake sesame and sea vegetable seasoning

Brush the hoisin sauce on the redfish.

Put the redfish on the grill.

Close the grill.

Walk away for some vague amount of time, maybe 10 minutes.

Chop the scallions and cilantro and cut the red and yellow cherry tomatoes in half.

Take the fish off the grill and pile the tomatoes, scallions, and cilantro on top.

Sprinkle with Eden Shake sesame and sea vegetable seasoning, which is a nice mix of black sesame seeds, seaweed, and salt.

Sprinkle a little fish sauce on top, if desired.

Serve with salad, rice, and a bowl of buttered

edamame

out of the shell.

On the Shelf

At some point I read an essay by the famous editor and book guy Jason Epstein in the

New Yorker

that discussed food and, more specifically, shopping for it in Chinatown. I had always loved wandering around Chinatown and eating there. But I hadn’t thought of its markets as anything other than spectacle. Reading him, I thought, Oh, you can actually buy stuff there and cook it—that sounds fun. For some reason I date my understanding of cooking as being part of a larger process of perusing and shopping to my reading that essay. Epstein’s latest book is

Eating,

but I have not yet read it. When I went to search for Epstein’s food essays online, I could not find any of them. I wonder if perhaps it was just one essay, and maybe it was ten years ago. I have lost all sense of time. Not finding the essay made me wonder if I had imagined this whole thing, but that is another matter.

KEITH DIXON

Alternate-Side Cooking

Keith Dixon is the author of two novels, Ghostfires and

The Art of Losing,

and

Cooking for Gracie,

a memoir-cookbook about cooking with and for a child. He is an editor for the

New York Times

and lives in Manhattan with his wife, Jessica, and their two daughters, Grace and Margot.

New York City residents who own cars struggle mightily with something called alternate-side parking, in which you’re forced to move your street-parked car once or twice a week (depending on where it’s parked) for an hour and a half or so (depending on where it’s parked) while the revving street cleaner sweeps by, scouring the gutters. After the street cleaner is gone, you scurry back to your desired spot—in time, you hope, to score a parking space just outside your building, where the car will remain until the next time it has to be moved. As long as you remember to move your car every week at the appointed times, you never get a parking ticket, and parking on the street begins to look like a pretty good deal—especially when compared with the extortionate cost of garaging a car in New York.

No one does this. No one remembers to move the car every week at the appointed times. What you do instead is this: You forget to move the car, and the next time you walk by it you notice that you have a pretty pumpkin-colored parking ticket stuffed under the wiper. At this point you remember that you were supposed to move the car and will now have to explain to your wife that you’re out a hundred and fifteen bucks. After I did this about twenty times, I realized that my only choice was to garage the car full-time and accept the cost as the price of forgetfulness. With the car safely tucked into the garage below my apartment, I assumed that I was finished with alternate-side perils forever. I was wrong.

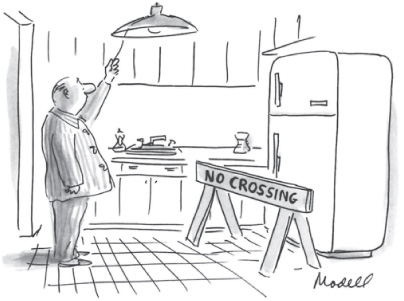

A new alternate-side hazard is making itself known in my house-hold. It appeared quietly and stealthily, but it’s there nevertheless. Vexingly, it’s a hazard related to the room of the house I cherish the most, and whose sanctity I strive to protect: the kitchen. Until recently, my rule over this room was both absolute and undisputed, which is exactly the way I liked it.

That’s all coming to an end now, thanks to this new hazard.

Let’s call it alternate-side cooking.

I’m a dad who cooks. My dad is also a dad who cooks. One clear difference between us: I treat cooking as a full-time mania (I’m the glazed-eyed fanatic walking aisle six on Tuesday night

just for fun

), while my dad regarded cooking as more of a creative weekend diversion and a chance to help out a little around the house. He began cooking years ago, when my mother, quite wisely, pulled a Tom Sawyer and managed to convince him that making meals for a large family all the time was lots of fun. His job limited him to cooking on weekends, though, which meant that the laborious work of preparing breakfast, lunch, and dinner at least five days a week for me and my three hungry brothers was left almost entirely to my mother.