Man With a Pan (21 page)

Everything I have made from this book of chocolate desserts has become my favorite version ever of that thing: chocolate chip cookies, double-chocolate brownies, cream-filled chocolate donuts. It’s fast becoming my favorite non-pie-based dessert cookbook.

IN THE TRENCHES

Daniel Moulthrop is a thirty-seven-year-old father of two boys and one girl, all under the age of six. The former host of the public radio show

The Sound of Ideas

on 90.3 WCPN in Cleveland, he is the curator of conversation for the Civic Commons, a Knight Foundation project in northeastern Ohio. His wife is from a food-obsessed family with Sicilian roots.

I’ll come home and my father-in-law will have dropped off eight pounds of Gala apples or something. It’s partly because he just loves food. He was the produce buyer at a grocery store. He can’t pass up a deal. When he sees a good melon, he has to buy it and share it with people. He’ll leave half a watermelon in our fridge, or a quarter of a honeydew, or something. One day my wife, Dorothy, and I came home and there were literally sixteen pecks of tomatoes on our dining room table. A peck is a half bushel. So we had sixteen rectangular boxes, slightly bigger than a shoe box, filled with beautiful Roma tomatoes. Dorothy and I were like, “Oh my God, what are we going to do?” We wanted to make sauce out of them, but the tomatoes ended up sitting on our table for a week. And we kept smelling them, and they’re great. But, you know if you’ve made sauce from scratch, you need a lot of time. It’s a whole-day thing. If you’re going to make that much sauce, that’s really going to take all day.

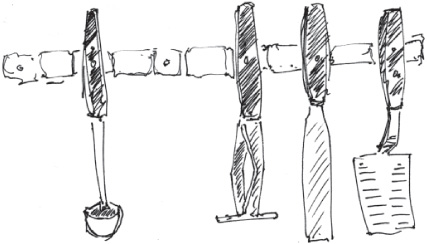

We recruited Dorothy’s parents to help us, and we woke up at five one morning. This was a few summers ago, back when we had only two kids. We had to get all our pots and pans out. Every burner was going. Then after everything cooks, you take everything, run it through the food mill into another pot. And the food mill pulls out the seeds and the skins. That is the miracle of the tool. If you don’t have one, you should have one. They’re so old fashioned. They look like they’re from the nineteenth century.

After you run it through the food mill, you still have to reduce the sauce because it’s still really watery. The last time we canned the tomatoes, we had so many burners going, and so much stuff going on, that we had to use our neighbor’s stove. I brought two pots over next door and said to them, “Just let this simmer for four hours, and I’ll be back.”

From those sixteen pecks of tomatoes or whatever it was, we got something like forty or fifty quart jars of sauce. But literally, I was working on this from five in the morning until eleven at night. Because after you cook it down, you then have to process the jars. You’ve got to sterilize them and put everything in there, making sure you’re doing it clean, and put the top on. Then you have to boil the jars for ten to fifteen minutes, and then you pull them out and let them cool down. That’s when they really get sealed, when they’re cooling down.

It was like an eighteen-hour day of making sauce and canning. We’ve done it twice. We didn’t do it last summer because it was a little too hectic. Our youngest was born in November of ’08, and it was just a little bit too much. It’s a huge time investment, but it’s so worth it. In the depths of winter, we had tomato sauce until March.

Our canning started with the tomatoes, but it didn’t stop there. A while later, my father-in-law said, “Come on, Dan, where’s your pickle recipe, you’re Jewish.” And I’m like, “I don’t have a pickle recipe, Dad.” He said, “Well, come on, you’re Jewish.” So I went online to find a pickle recipe. I looked at a few different recipes, and I picked the one that has, like, the most positive comments, essentially. I found a great recipe that is really simple. It has a brine and fresh dill, a few cloves of garlic, and some peppercorns. And we don’t get any more complicated than that.

My father-in-law buys these great pickling cucumbers. They fit well in a quart jar. The process is so much easier. I can show up at his house at five o’clock in the afternoon, and he’ll usually have taken care of the basic prep work of washing the cucumbers and chilling them. You have to chill the cucumbers, and so he ices them down in a cooler. If he’s done that already, then I can work from seven until ten and make, like, thirty jars of pickles. I can do it after work. That’s what we did this summer.

The first time I did it, my son was involved. The second time he was doing something else. You kind of have to strike when you’ve got all the fresh food. But the first time was great. He just kept eating the raw cucumbers out of the cooler. It was great fun. And the pickles turned out great. Everybody who tastes these pickles was like, “Oh my God, that’s the best pickle I’ve ever had.” They really are the best pickle you’ve had.

Then I did strawberries. One day, Dorothy and I were with the kids at the farmer’s market. It was late June and the strawberries were just amazing. They had all these small but supersweet strawberries. I bought two quarts. We had gotten separated at the market, and when I got back to Dorothy, it was like the opposite of “The Gift of the Magi”—she’s got two quarts. I thought, What are we going to do with all these strawberries?

One night, I said, “I’m just going to can them.” I didn’t know what I was doing at all. I’d never canned fruit before in my life. I just knew the basic process: I cooked them down. I found a way to make jam without adding pectin. But you have to add the sugar at just the right temperature. I tried, but it wasn’t thickening. What I came up with was kind of more syrupy than jammy.

A couple of months later, I pulled a jar out and poured its contents over vanilla ice cream, and it was the most blissfully beautiful thing. It was just an experiment. I was like, I’ve never done this before, but I’ll try it. It’s not rocket science, it’s not brain surgery; it’s just food.

Recipe File

Pickles

This pickle recipe is adapted from a recipe at allrecipes.com, contributed by a woman named Sharon Howard. It gets five out of five stars there, and deservedly so. Hardware you might need: canning jars and lids, canning tongs, and a superhuge pot for boiling water.

8 pounds 3- to 4-inch-long pickling cucumbers

4 cups white vinegar

12 cups water

⅔ cup kosher salt

16 cloves garlic, peeled and halved

Fresh dill weed

Wash the cucumbers and place in the sink with cold water and lots of ice cubes. Soak in ice water for at least 2 hours but no more than 8 hours. Refresh the ice as required. Sterilize 8 1-quart canning jars and lids in boiling water for at least 10 minutes.

In a large pot over medium-high heat, combine the vinegar, water, and pickling salt. Bring the brine to a rapid boil.

In each jar, place 2 half cloves of garlic, 1 head of dill, then enough cucumbers to fill the jar (about 1 pound). Then add 2 more garlic halves and 1 sprig of dill. Fill the jars with hot brine. Seal the jars, making sure you have cleaned the jars’ rims of any residue.

Process the sealed jars in a boiling-water bath. Process quart jars for 15 minutes.

Store the pickles for a minimum of 8 weeks before eating. Refrigerate after opening. Pickles will keep for up to 2 years if stored in a cool, dry place.

Note: My father-in-law, son, and I tend to cook in bulk, which is to say we basically multiply this recipe by a factor of 4 or 5. We do this for a few reasons: (1) it’s fun; (2) the pickles make great gifts; and (3) the pickles turn out so good that you’ll want to make sure you have some left over after you give away a case as gifts. I have notes on my recipe that read “2 bags ice, 2 gallons vinegar, 1 box kosher salt” and “2 pecks = 2 cases.” (A peck, by the way, is ¼ bushel, or 8 quarts.) At that volume, we chill the cukes in a cooler, in the sink, and in whatever other large containers we can find. Also, we have used whole black peppercorns, roughly 1 teaspoon in each jar, to great effect in the pickles.

To process the jars, seal them up tight, put them in the boiling water so that the water covers the jars entirely for 15 minutes, and then take them out and let them cool. As they cool, the air inside contracts and pulls the lid tight; you’ll hear the lids pop, which is very satisfying.

Tomato Sauce

This recipe is borrowed and adapted from Biba Caggiano’s

Biba’s Taste of Italy,

one of my wife’s all-time favorite cookbooks. (If I didn’t note this before, I should have: Dorothy is a far better cook than I.) Hardware you might need: canning jars and lids, canning tongs, a food mill (nifty contraption, highly recommended), and a superhuge pot for boiling water.

12 pounds very ripe tomatoes, preferably plum (Roma) tomatoes, cut into chunks

2 large onions, coarsely chopped

5 carrots, cut into small rounds

5 celery stalks, cut into small pieces

1 cup loosely packed parsley

1 teaspoon coarse salt (or more, to taste)

1 small bunch of basil, stems removed (20 to 30 leaves)

¼ cup extra-virgin olive oil

Combine everything but the basil in a big pot and cook over medium heat for 45 minutes to an hour, until the tomatoes start to fall apart and the other vegetables are soft.

Puree the mixture in a food processor or blender, or with an immersion blender (by far the easiest of the three options). Then pass the mixture through a food mill outfitted with the disk with the tiniest holes. This removes the skins and seeds.

Return the sauce to the stove and stir in the basil. Cook slowly until the sauce thickens to something approaching what you want to put on pasta.

While the sauce is cooking, sterilize your jars and lids in boiling water.

Fill your jars—just as many at a time as you can process in your largest pot, which should still be filled with boiling water because you just sterilized the jars and lids. Make sure you leave about ½ inch of space from the rim of the jar, and make sure you wipe the rims clean with a hot, damp towel. Place the lids on top and tightly seal the rings.

Process the jars in boiling water for 20 to 25 minutes, then remove them from the water and leave them to cool completely. The lids will pop down as they cool. This seals the jars. You can test the seal by pressing on the center of each lid. If the lid stays firm and doesn’t flex up or down and doesn’t pop back, the lid is sealed properly. Store in a cool, dry place for up to 8 months.

Note: When we last made sauce, we noticed that we used 6 pecks (roughly 100 pounds) of Roma tomatoes, 6 pounds onions, 4 pounds carrots, 4 pounds celery, 3 bunches of parsley, and probably all the basil growing in our garden. That yielded 30 quarts of sauce.

THOMAS BELLER

On Abundance

Thomas Beller is the author of two works of fiction,

Seduction Theory

and

The Sleep-Over Artist,

and a collection of personal essays,

How to Be a Man.

His most recent book is the anthology

Lost and Found: Stories from New York.

A former staff writer at the

New Yorker

and the

Cambodia Daily,

he is a cofounder and editor of

Open City

magazine and Mrbellersneighborhood.com. He teaches creative writing at Tulane University.

1.

The audience began to clap. I was the first one out the door. I walked quickly into the reception area, where I saw lemon squares. It took a few seconds for it to sink in that this was all there was. The event was at a university where receptions range from a few cookies to hunks of meat and seafood. Usually I don’t care, but that night I was hoping for something that could substitute for dinner. I had played basketball and lifted weights earlier, but it wasn’t hunger, exactly, that was causing my problem. It was a question of scarcity. A few weeks earlier I had made a familywide announcement that it was time for some austerity. We had been plundering the local Whole Foods, sampling the considerable restaurant options, living beyond our means. It was time for a retrenchment, a pulling back, the return of savoring. In a display of leadership I put myself on a personal budget of five dollars a day. It was like someone who takes up jogging by announcing they will do five miles every morning. This was day four. I checked the time. It was 8:47 p.m.

Nine p.m. is a significant hour for me in my adopted city of New Orleans. It is when Whole Foods locks its doors. New Orleans, unlike New York, closes up early and with finality when it comes to food. The Winn-Dixie closes at 11:00 p.m. Beyond that, the offerings are limited to an all-night grocery in the French Quarter, where I once went for grapes, and gas station convenience stores, most of which are sealed behind Plexiglas. At those places you have to ask the attendant to get you something.

It’s oddly intimate to have a stranger hold up an ice cream sandwich or a flavor of vitamin water as though to say, Is this what you wanted? while you nod enthusiastically or shake your head. Once, at the end of a vexingly Chaplinesque session of trying to direct the person inside to what I wanted, I found myself shouting, “Yes! The little white donuts! Yes! Yes!” at which point, giddy with triumph, I turned around to see a line of people waiting to pay for their gas.