Mark Griffin (20 page)

Authors: A Hundred or More Hidden Things: The Life,Films of Vincente Minnelli

Tags: #General, #Film & Video, #Performing Arts, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors, #Minnelli; Vincente, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Motion Picture Producers and Directors - United States, #Biography & Autobiography, #Individual Director, #Biography

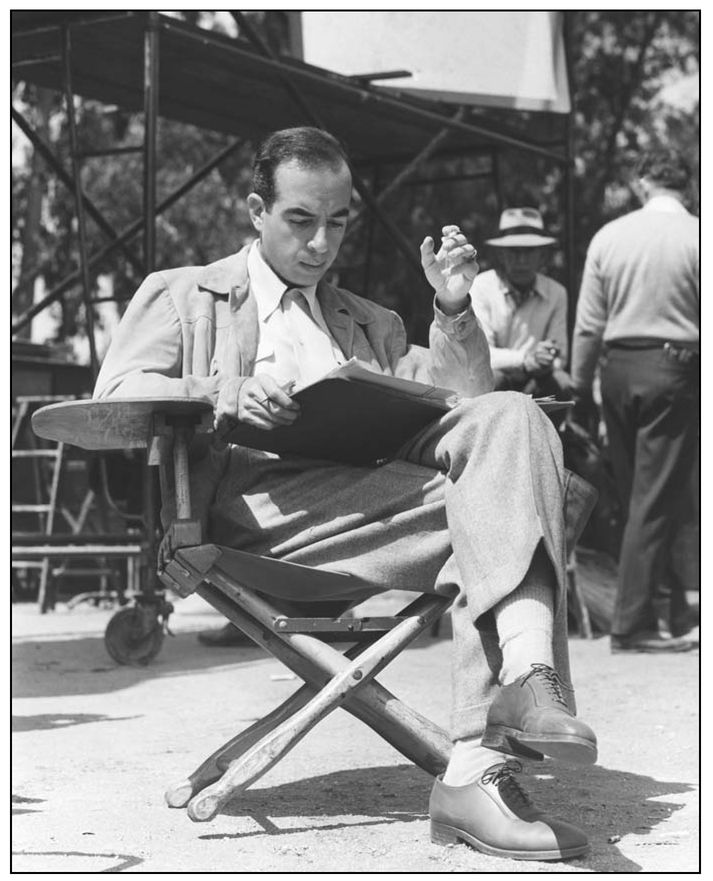

Minnelli studies the script of

Yolanda and the Thief

, 1945. PHOTO FROM THE AUTHOR’S COLLECTION

Yolanda and the Thief

, 1945. PHOTO FROM THE AUTHOR’S COLLECTION

11

Dada, Dali, and Technicolor

AS MARRIAGE RUMORS SWIRLED, Minnelli began preparing his next film,

Yolanda and the Thief

. This would be a lavish musical based on a whimsical fable by

Madeline

creator Ludwig Bemelmans and Jacques Thery that had appeared in the July 1943 issue of

Town and Country

. The story concerns a slick swindler who sets his sights on an outlandishly wealthy but spiritually attuned heiress. The con man gets closer to Yolanda’s fortune by posing as her guardian angel. In some ways, the plot resembled Fred Astaire’s “This Heart of Mine” vignette from

Ziegfeld Follies

, and that sequence may have given Freed the idea to cast Astaire as

Yolanda

’s suave charlatan, Johnny Riggs. Freed and MGM’s front office were also banking on

Yolanda

to imitate the success of

You Were Never Lovelier

, the 1942 Columbia triumph that had paired Astaire with Rita Hayworth and that featured a somewhat similar storyline.

Yolanda and the Thief

. This would be a lavish musical based on a whimsical fable by

Madeline

creator Ludwig Bemelmans and Jacques Thery that had appeared in the July 1943 issue of

Town and Country

. The story concerns a slick swindler who sets his sights on an outlandishly wealthy but spiritually attuned heiress. The con man gets closer to Yolanda’s fortune by posing as her guardian angel. In some ways, the plot resembled Fred Astaire’s “This Heart of Mine” vignette from

Ziegfeld Follies

, and that sequence may have given Freed the idea to cast Astaire as

Yolanda

’s suave charlatan, Johnny Riggs. Freed and MGM’s front office were also banking on

Yolanda

to imitate the success of

You Were Never Lovelier

, the 1942 Columbia triumph that had paired Astaire with Rita Hayworth and that featured a somewhat similar storyline.

As with virtually every musical announced by MGM, Judy Garland was at one time slated to play Yolanda Aquaviva, the most beloved resident of the mythical South American country of Patria—“the land of milk and money.” Despite her interest in appearing in

Yolanda

, Garland would ultimately be assigned to

The Harvey Girls

, a pet project of her mentor-arranger Roger Edens. In March 1944, the studio next announced that Lucille Ball, fresh from her triumph in Metro’s

Best Foot Forward

, would play the wide-eyed heiress. Ultimately, the role was given to Freed’s comely protégé, Lucille Bremer. After receiving positive notices as a result of her memorable pairing with Fred Astaire in

Ziegfeld Follies

, Bremer was being groomed for Garland-sized superstardom. For

Yolanda and the Thief

, Bremer’s name would be

billed after Astaire’s but above the title, a signal to audiences that there was a new star in Metro’s firmament.

Yolanda

, Garland would ultimately be assigned to

The Harvey Girls

, a pet project of her mentor-arranger Roger Edens. In March 1944, the studio next announced that Lucille Ball, fresh from her triumph in Metro’s

Best Foot Forward

, would play the wide-eyed heiress. Ultimately, the role was given to Freed’s comely protégé, Lucille Bremer. After receiving positive notices as a result of her memorable pairing with Fred Astaire in

Ziegfeld Follies

, Bremer was being groomed for Garland-sized superstardom. For

Yolanda and the Thief

, Bremer’s name would be

billed after Astaire’s but above the title, a signal to audiences that there was a new star in Metro’s firmament.

Many on the lot were surprised that Bremer rose through the ranks as swiftly as she did. “She came out of nowhere,” says former contract dancer Judi Blacque. “We certainly never thought that she would become a major star. Don’t misunderstand me. She was very nice. Very attractive. And she could dance. But when you look at what was available in Hollywood at that time, it was incredible that she got as far as she did.”

1

1

After the unqualified success of

Meet Me in St. Louis

, Freed felt that he could confidently turn to screenwriter Irving Brecher to translate the Thery-Bemelmans prose into a screenplay that retained the original story’s childlike innocence while managing to keep war-weary audiences awake. “The story was nothing,” Brecher admitted decades later. “I didn’t like it. But Freed wanted to make it . . . and to star Lucille Bremer, who had been in

Meet Me in St. Louis

, and, if she was not having an affair with Arthur Freed, was at least being coveted by Freed. In any case, I didn’t want to work on

Yolanda

. Nothing was happening with it, and I didn’t think there was a picture in it that I could do that would be worth anything.”

2

Meet Me in St. Louis

, Freed felt that he could confidently turn to screenwriter Irving Brecher to translate the Thery-Bemelmans prose into a screenplay that retained the original story’s childlike innocence while managing to keep war-weary audiences awake. “The story was nothing,” Brecher admitted decades later. “I didn’t like it. But Freed wanted to make it . . . and to star Lucille Bremer, who had been in

Meet Me in St. Louis

, and, if she was not having an affair with Arthur Freed, was at least being coveted by Freed. In any case, I didn’t want to work on

Yolanda

. Nothing was happening with it, and I didn’t think there was a picture in it that I could do that would be worth anything.”

2

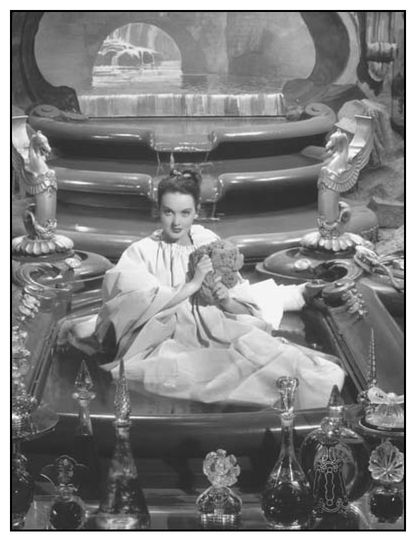

Whereas Brecher’s screenplay for

Meet Me in St. Louis

had contained universal situations and humor that anyone with a slightly off-center family could relate to,

Yolanda

occupied more rarefied territory. Minnelli would later boast that

Yolanda

contained “the first surrealist ballet ever used in pictures.” Bold and Dali-esque in design, Astaire’s “Dream Ballet” was certainly striking, but including a surrealistic ballet in an already fanciful musical was not unlike piling a hot fudge sundae on top of a banana split. Everything in Yolanda’s world—from her baroque bathtub to her singing servants—was the stuff of absurdist, off-the-wall fantasy. As Noel Langley, one of the screenwriters of

The Wizard of Oz

, once observed: “You cannot put fantastic people in strange places in front of an audience unless they have seen them as human beings first.”

3

Meet Me in St. Louis

had contained universal situations and humor that anyone with a slightly off-center family could relate to,

Yolanda

occupied more rarefied territory. Minnelli would later boast that

Yolanda

contained “the first surrealist ballet ever used in pictures.” Bold and Dali-esque in design, Astaire’s “Dream Ballet” was certainly striking, but including a surrealistic ballet in an already fanciful musical was not unlike piling a hot fudge sundae on top of a banana split. Everything in Yolanda’s world—from her baroque bathtub to her singing servants—was the stuff of absurdist, off-the-wall fantasy. As Noel Langley, one of the screenwriters of

The Wizard of Oz

, once observed: “You cannot put fantastic people in strange places in front of an audience unless they have seen them as human beings first.”

3

There is nothing earthbound about

Yolanda

, which is both part of its charm and part of its problem. A prime example of Minnelli at his most uninhibited and self-indulgent, the movie showed what could happen when Vincente sacrificed story to style. As would occur later with

The Pirate

, the stylistic excesses of

Yolanda

would delight Minnelli fans but confound mainstream audiences expecting a more conventional musical-comedy outing.

Yolanda

, which is both part of its charm and part of its problem. A prime example of Minnelli at his most uninhibited and self-indulgent, the movie showed what could happen when Vincente sacrificed story to style. As would occur later with

The Pirate

, the stylistic excesses of

Yolanda

would delight Minnelli fans but confound mainstream audiences expecting a more conventional musical-comedy outing.

Bremer, while not untalented, was miscast as the pious, convent-bred Yolanda—though, to be fair, even Judy Garland’s trademark sincerity would have been taxed with lines such as, “I’m not the only one who’s happy tonight. . . . The man in the moon is smiling.” It also doesn’t help that in the

early scenes, Bremer is noticeably older than her convent classmates, who, in their pinafores and picture hats, seem to have emerged directly from the pages of

Madeline

. Although

Yolanda

has its fiercely devoted partisans, there was only one sequence in the film that seemed to please everybody—the justly celebrated “Coffee Time.” Freed from their arch dialogue and contrived situations, Astaire and Bremer were finally allowed to do what they did best: dance. During this one number (choreographed by Eugene Loring), Minnelli’s movie suddenly and all too fleetingly sprang to life.

early scenes, Bremer is noticeably older than her convent classmates, who, in their pinafores and picture hats, seem to have emerged directly from the pages of

Madeline

. Although

Yolanda

has its fiercely devoted partisans, there was only one sequence in the film that seemed to please everybody—the justly celebrated “Coffee Time.” Freed from their arch dialogue and contrived situations, Astaire and Bremer were finally allowed to do what they did best: dance. During this one number (choreographed by Eugene Loring), Minnelli’s movie suddenly and all too fleetingly sprang to life.

Taking the plunge: Yolanda Aquaviva (Lucille Bremer) in her luxurious, baroque bathtub in

Yolanda and the Thief

.

Yolanda

’s coauthor Ludwig Bemelmans had high hopes for the film’s leading lady. As he told Arthur Freed: “It is so nice and so exciting to sit at the birth of what will be a great star.” PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

Yolanda and the Thief

.

Yolanda

’s coauthor Ludwig Bemelmans had high hopes for the film’s leading lady. As he told Arthur Freed: “It is so nice and so exciting to sit at the birth of what will be a great star.” PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

In the end, not even this exhilarating sequence could save

Yolanda

from its fate. To wartime audiences accustomed to the likes of

Four Jills in a Jeep

,

Yolanda

must have seemed as accessible and inviting as a Jackson Pollock canvas. “

Yolanda

is such an interesting failure because it has got these amazing flights of imagination,” says writer Clive Hirschhorn. “I mean, ‘Coffee Time’ is just wonderful and the color scheme throughout the film is simply breathtaking, but the film as a whole just doesn’t work because it doesn’t really invite you in. It’s almost too experimental. Too clever.”

4

Yolanda

from its fate. To wartime audiences accustomed to the likes of

Four Jills in a Jeep

,

Yolanda

must have seemed as accessible and inviting as a Jackson Pollock canvas. “

Yolanda

is such an interesting failure because it has got these amazing flights of imagination,” says writer Clive Hirschhorn. “I mean, ‘Coffee Time’ is just wonderful and the color scheme throughout the film is simply breathtaking, but the film as a whole just doesn’t work because it doesn’t really invite you in. It’s almost too experimental. Too clever.”

4

As Astaire recalled, “We all tried hard and thought we had something, but as it turned out, we didn’t. There were some complicated and effective dances which scored, but the whole idea was too much on the fantasy side and it did not do well.”

Edwin Schallert’s mixed review in the

Los Angeles Times

seemed to sum up the general consensus: “‘Not for realists’ is a label that may be appropriately affixed to

Yolanda and the Thief

. It is a question, too, whether this picture has the basic material to satisfy the general audience, although in texture and trimmings it might be termed an event.”

Los Angeles Times

seemed to sum up the general consensus: “‘Not for realists’ is a label that may be appropriately affixed to

Yolanda and the Thief

. It is a question, too, whether this picture has the basic material to satisfy the general audience, although in texture and trimmings it might be termed an event.”

But, as usual, it was Judy Garland who nailed the entire experience with a devastating one-liner. After a cooly received sneak preview of

Yolanda

, it became clear that despite Freed’s best efforts, Bremer lacked genuine star appeal and Minnelli’s musical was something of a misfire. As Garland passed a dispirited Arthur Freed, she quipped: “Never mind, Arthur, Pomona isn’t Lucille’s town.”

5

Yolanda

, it became clear that despite Freed’s best efforts, Bremer lacked genuine star appeal and Minnelli’s musical was something of a misfire. As Garland passed a dispirited Arthur Freed, she quipped: “Never mind, Arthur, Pomona isn’t Lucille’s town.”

5

“The picture made money,” Minnelli would assert in his autobiography, but the MGM ledgers told a different story, estimating a net loss of $1,644,000 (in 1945 dollars). Despite the paltry box-office returns and the lukewarm reviews,

Yolanda and the Thief

, like several of Vincente’s later efforts, retroactively achieved cult status, attracting a devoted following of fans who found the film’s bizarre mélange of Dada, Dali, and Technicolor irresistibly appealing. Among the faithful were MGM arranger Kay Thompson and her

Eloise

illustrator Hilary Knight, who both embraced the inspired lunacy that is

Yolanda

.

Yolanda and the Thief

, like several of Vincente’s later efforts, retroactively achieved cult status, attracting a devoted following of fans who found the film’s bizarre mélange of Dada, Dali, and Technicolor irresistibly appealing. Among the faithful were MGM arranger Kay Thompson and her

Eloise

illustrator Hilary Knight, who both embraced the inspired lunacy that is

Yolanda

.

“We were always talking about things that we liked or Kay’s experiences at MGM, which were hilarious but usually not very kind to the people involved,” Knight remembers. “We also talked about things that we loved about movies and we both agreed that we loved

Yolanda

”—and especially Mildred Natwick’s scatterbrained, chihuahua-toting Aunt Amarilla, who spouts the movie’s most delectable lines. At one point, the pixilated Amarilla turns to a devoted servant and imperiously demands, “Do my fingernails immediately . . . and bring them to my room!”

Yolanda

”—and especially Mildred Natwick’s scatterbrained, chihuahua-toting Aunt Amarilla, who spouts the movie’s most delectable lines. At one point, the pixilated Amarilla turns to a devoted servant and imperiously demands, “Do my fingernails immediately . . . and bring them to my room!”

In addition to delivering the film’s wittiest zingers, the veteran character actress also had an opportunity to observe Freed and Bremer in close proximity. While the studio rumor mill would inextricably link the producer and his reluctant star, there was at least one colleague who thought otherwise. “Natwick told me that she thought Lucille had never succumbed to Arthur,” Hilary Knight reveals. “Lucille’s mother was always with them, even on the set . . . always protecting her baby from Arthur.”

6

6

“ABSORBED . . . DIRECTOR VINCENTE MINNELLI studies the script of

Yolanda and the Thief

, oblivious of the cameraman snapping his picture,” read the caption accompanying a publicity photo of Minnelli on the set of

his latest production. The rare glimpse of Judy Garland’s husband engrossed in his work was officially approved by Hollywood’s Advertising Advisory Council on June 25, 1945, just ten days after the much-discussed Minnelli-Garland nuptials had taken place at Judy’s mother’s house in Beverly Hills. It was an intimate ceremony with none of the customary Hollywood hoopla that usually attended a celebrity wedding, though MGM was well represented—by Arthur Freed, publicity chief Howard Strickling, and even Louis B. Mayer, who gave the bride away.

Yolanda and the Thief

, oblivious of the cameraman snapping his picture,” read the caption accompanying a publicity photo of Minnelli on the set of

his latest production. The rare glimpse of Judy Garland’s husband engrossed in his work was officially approved by Hollywood’s Advertising Advisory Council on June 25, 1945, just ten days after the much-discussed Minnelli-Garland nuptials had taken place at Judy’s mother’s house in Beverly Hills. It was an intimate ceremony with none of the customary Hollywood hoopla that usually attended a celebrity wedding, though MGM was well represented—by Arthur Freed, publicity chief Howard Strickling, and even Louis B. Mayer, who gave the bride away.

Vincente and Judy’s wedding day, June 15, 1945. Best man Ira Gershwin, Minnelli, Garland, Louis B. Mayer (who gave the bride away), and studio publicist Betty Asher (Judy’s maid of honor) pose for photographers. The ceremony took place at Judy’s mother’s house in Beverly Hills. PHOTO COURTESY OF PHOTOFEST

Other books

Five Run Away Together by Enid Blyton

A Family Madness by Keneally, Thomas;

School For Heiresses 3- Beware A Scot's Revenge by Sabrina Jeffries

Los hijos de Húrin by J.R.R. Tolkien

Material Girl 2 by Keisha Ervin

Crisis by Ken McClure

Mirror in the Sky by Aditi Khorana

Los presidentes en zapatillas by Mª Ángeles López Decelis

Lady Silence by Blair Bancroft

Sorcerer's Son by Phyllis Eisenstein