Metallica: This Monster Lives (19 page)

Read Metallica: This Monster Lives Online

Authors: Joe Berlinger,Greg Milner

Tags: #Music, #Genres & Styles, #Rock

By the time the interview was published in March, the “sequence of events” was definitely in motion. Jason was gone, and we had arrived to film a band thrown into chaos. Metallica’s lack of a bassist was the least of its problems. Jason’s departure had brought out all sorts of issues of trust and communication within the band. Those issues are really the crux of the movie. As James says, Jason’s exit made James realize the extent to which his own fear of abandonment made him unable to love people without smothering them; nothing in

his troubled family history ever taught him differently. “The way I learned how to love things was just to choke ’em to death,” he explains in

Monster.

“You know, ‘Don’t go anywhere, don’t leave.’ “If Jason had not announced he was leaving, Q Prime would not have suggested that Metallica hire Phil Towle to try to salvage the situation. So it’s no exaggeration to say that without Jason

Some Kind of Monster

would be a vastly different (and probably not as interesting) movie.

The films that Bruce and I have made are about conflicts that have arisen in small communities.

Brother’s Keeper

and both

Paradise Lost

films look at people who’ve known one another all their lives and are now forced by new circumstances to reassess what their relationships mean. We’ve had to learn to do our work with tact and diplomacy—to ensure we don’t ruin our chances of making the film, of course, but also to ensure that we’re as fair as possible to both sides. We want to capture a situation as faithfully as possible, and the last thing we want to do is disrupt the often complex and interwoven relationships that connect our subjects. In

Brother’s Keeper

, we were dealing with a pretty stable set of alliances, especially when it became clear that the town of Munnsville was rallying around the Wards. The

Paradise Lost

films, however, presented us with a much more complicated scenario. The murders had polarized a town where everyone knew one another. It was a tricky balancing act to move between the world of the accused and the victims’ families. We gradually won the trust of all sides, to the extent that all the different legal teams invited us to film their strategy meetings, an enormous leap of faith considering the damage we could have done by not being discreet. As the thread that connected the interested parties, we were often pumped for information and had to be very careful about what we said and to whom we said it.

1

Despite its rock-and-roll pedigree,

Monster

touches on many of the same themes as our previous films. Every rock band is a tiny community. A band that operates as a professional moneymaking unit is even more like a microcosm of society, because the people in the band have to learn to work together in order to make the product that provides their livelihood. The guys in Metallica aren’t in any danger of starving, but the art they make wouldn’t exist if any one band member were unsure of—or unwilling to accept—his role. For two decades, they operated under conditions that weren’t particularly healthy but which served to get the job done. It was as though they were always working under emergency rules. It was our luck as filmmakers that we entered their lives just when these conditions became unbearable. Lars himself told

Rolling Stone

that

Monster

isn’t a film about rock—it’s a film about relationships. Somehow we

managed to make a film about a heavy-metal band that tackled the same themes as our film about illiterate brothers and our film about alienated teens falsely accused of murder.

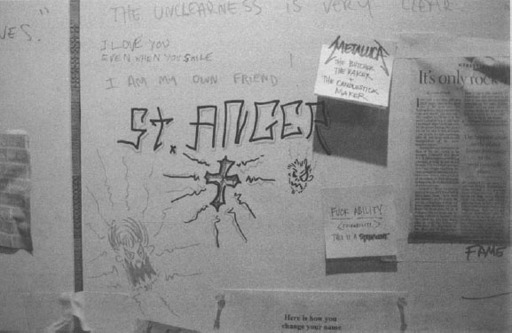

The album’s title emerged from the “idea board” at HQ. (Courtesy of Bob Richman)

We took great care not to disrupt the relationships within Metallica, especially at a time when they were so tenuous. This wasn’t always easy. It was especially challenging when we decided, during the summer of 2001, to approach Jason about doing an interview. As James’s hiatus stretched on, we were looking for things to film, and we’d heard that Jason was rehearsing with Echobrain for a possible tour. Phil was always very adamant in his belief that this relationship—Jason and Metallica—was not over (Phil would be proved right more than once). We didn’t want to do anything to disrupt the process of reconciliation. Since Jason had zero interest in talking to Phil, it seemed quite likely that he wouldn’t want to talk to us. I certainly would have understood his unwillingness to trust two guys hired by Metallica to make a Metallica movie that just happens to begin at the commencement of the “post-Jason” era. Besides, Jason left the band because of James’s insistence that things be done his way, so why would Jason want to give James the satisfaction of participating in this latest Metallica undertaking?

Jason, you may recall, was the Metallica member who seemed the most enthused about doing a film when we pitched the band in 1999. He also gave me the most time when we made the Metallica

FanClub

episode for VH1. He was no less gracious when we asked him to appear in

Monster.

We agreed to shoot Jason and Echobrain in a few weeks but didn’t think to tell Metallica about it. My rationalization was that Lars and Kirk had enough on their minds, so we should just be pros and carry on our project without keeping them informed of our every move. But as the shooting date approached, I began to feel funny about our contact with Jason. I had to admit to myself that I was deliberately not telling Lars because I was afraid he might not approve. A few days before we did the shoot, I finally forced myself to call Lars. I took a deep breath and dialed his cell number. When he answered, I got right to the point. I told him that I felt he should know we’d been speaking to Jason about filming him and his new band, and that Lars should tell me if he had any problem with this. There was a long silence. Finally, Lars muttered what sounded like assent and then quickly changed the subject.

Lars’s usual attitude toward us filming anything was, “If you think it’s important, do it.” During the two years of filming, his long silence and rushed answer to my question about shooting Jason was the closest he ever came to saying no. The fact that we considered Jason and Echobrain important enough to film must have stuck in Lars’s mind, because the subject of Jason came up a few days later in a therapy session. Lars was lamenting the sorry state of Metallica. “I think we should call Jason up, have him come over and play guitar, and the four of us will continue,” he joked.

Bob asked what Jason thought of the situation with James. “I didn’t talk to him about any of this,” Lars replied.

“I talked to him,” Kirk said. I think this took everyone by surprise.

“What does he know?” Phil asked.

“Oh, I gave him a very condensed version of what’s going on.”

Lars asked, with noticeable trepidation, “Did you tell him every single detail?”

Kirk laughed and made a pained expression. “No, I did not.” Lars, relaxing a little, laughed along with him. “And he was surprised that it had gotten to this point,” Kirk continued.

“Did you tell Jason that James had a breakdown because of Jason’s behavior?” Phil asked, smiling.

“I told him that, you know, Jason’s role played a—”

“Pushed him over the edge?”

“Well, that it played a huge part in that.”

“I’m joking about that,” Phil said.

Kirk continued by saying he told Jason that James had “a lot of remorse” about how he treated Jason. “And Jason was shocked. He said, ‘Really?’ in that Jason kind of way that he does when he’s just blown away”

Phil turned to me. “Jason gets interviewed tomorrow, right?”

I nodded. “I’ll be filming Jason tomorrow.”

“Really?” Kirk said. “That’s interesting.”

Lars, who had resisted asking me any details about our Jason plans, now asked, “Doing what?”

“Rehearsing with his new band.”

“Great.”

What was most striking about interviewing Jason was how angry he was. Nine months had passed since he’d left Metallica, but he was still seething with resentment. Phil was still very much on his mind. As we learn in

Monster

, he considered the idea of bringing in a therapist to be “really fucking lame and weak”—not just ineffectual, but also a symbol of how ridiculous Metallica’s interpersonal dynamics had become and how little everyone now seemed to care about making music: “The biggest heavy band of all time, and the things we’ve been through and the decisions we’ve made, about

squillions

of dollars and

squillions

of people—and

this

, we can’t get over

this

?”

I got the feeling that underneath Jason’s rage there was still a lot of uncertainty about his decision to leave. It was also clear that Jason had, over the years, internalized the idea that he was somehow different from the bandmates who never quite accepted him. In the

Playboy

interviews, the other three, recalling their early days, talked about how slutty they were during their early tours, how they, for example, would often “share” the same groupies. “I don’t think there’s anyone in the band who hasn’t had crabs a couple of times, or the occasional ‘drip-dick,’” Lars says. During our interview, Jason made a point of bringing up Lars’s comment and taking issue with it: “Not me, pal,” he said with a disgusted look on his face. “I never played the games that those guys did.”

One inevitable effect of interviewing Jason is that Bruce and I found ourselves in the uncomfortable but familiar role of go-between. Just as the members

of Metallica had used Tannenbaum to communicate with one another, they now used us. Jason wanted to know what the guys in Metallica were saying about him, and they wanted to know what Jason said about them. But unlike Tannenbaum, we were being funded by Metallica, which made our relationship with Jason a little tricky. It was awkward to film someone at the band’s expense and then feel like that support obligated us to divulge information. We didn’t want to perpetuate a he-said-she-said situation, but on the other hand, since they were funding the film, we didn’t feel like we could withhold information if Metallica asked for it. As it turned out, I think we actually eased some of the collective tensions a bit, once everyone involved figured out that their emotions were more complex than simple rancor and resentment. This would not be the last time we found ourselves in the middle of these two parties. Phil was right: this relationship wasn’t over.

Our decision to keep filming Echobrain led to one of the most emotionally raw scenes in

Monster,

and probably the lowest point for Lars during the James-less period. Our production manager in San Francisco, Cheryll Stone, called to tell us that she’d noticed an ad for an upcoming Echobrain show at Bimbo’s, a local club. We called Lars to see if he knew about the show. It turned out he didn’t, but we didn’t hear back from him until a few days later, the day of the show, when he surprised us a little by saying he planned to go. Kirk and Bob also decided to check it out. On the ride over, Lars seemed very nervous. It was not Metallica’s night. As we see in

Monster,

the enthusiastic reaction Echobrain got from the crowd made Lars feel like Metallica’s time had passed. (The fact that Jason didn’t stick around to greet them in the dressing room probably hurt, too.) “Jason’s the future, Metallica’s the past,” he says in

Monster,

burying his head in his hands.

2

The scene takes a tragicomic turn when Bob begins pointing out all the people connected to the Metallica organization who are now working for Echobrain. Consistent with the general “loser” vibe of the evening was the fact that Lars and Kirk, not just huge rock stars but also

local

huge rock stars, appeared to be recognized by virtually nobody.

The conflict with Jason provided us with a conflict capable of launching a story arc, but I like to think that Jason is also largely responsible for triggering the issues that

Monster

explores. Metallica’s decision to make

St. Anger

in a democratic fashion came about largely because the absence of such a method was a key reason Jason left. I think James and Lars always thought their iron grip on the band’s music was expedient, the most efficient way to get things done. After seeing the catastrophic effects that two decades of this method finally

had on Metallica, they made the decision to make records the way Jason always wanted. Opening up this process was particularly hard on James, since it brought things he was already struggling with in his personal life—issues of love and trust—into his musical life, which had always been his last refuge from the world. And

that’s

really what

Monster

is about. By leaving, Jason forced James to confront the fact that they’d never really known each other, and that James and Lars had also never really known each other. These discoveries are the foundation on which

Some Kind of Monster

is built. They’re also the reason—perhaps the crucial reason—that I bet Metallica will continue to make music for years to come. Jason had to sacrifice himself to make the band what it is today.