Metallica: This Monster Lives (17 page)

Read Metallica: This Monster Lives Online

Authors: Joe Berlinger,Greg Milner

Tags: #Music, #Genres & Styles, #Rock

“This is the stage where he heals himself and we’re healing ourselves.” It’s clear that Phil was doing more than just giving a pep talk to the troops. He was also urging them to reassess their relationships with each other, and especially their individual relationships with James. Phil’s thinking seemed to be that in order for Metallica to be reborn, everyone would have to experience some of what James was going through: rethinking things about themselves that they took for granted. In putting their relationships with one another under the microscope, a lot of stuff was being dredged up. As some of the band’s immediate anxiety about James subsided a bit, resentment toward him began to set in. Some of the resentment was directed at the immediate situation, the limbo caused by James’s departure. Kirk professed to have infinite patience, seeing the break as an opportunity to work on his surfing skills, but Bob and Lars disliked the inactivity almost immediately. Phil did his best to direct these hurt feelings in a positive direction.

“As long as I can remember, I have never wanted to work more than these

days right now,” Lars said a few weeks into the James-less era. “Coming back to San Francisco and not having anything to do—it’s been a strange week. I’ve gotten really drunk, twice, and just walked around and wondered what to do with myself.” Bob concurred. Even Kirk responded by saying that he really felt “there was work to be done.”

Phil’s reply was a careful display of tact. “I think it might make a difference to James’s mentality if he knows that each of us, as individuals, is working on our shit. If he knows that the way you’re handling it is—and I’m just using this as an example—that you’re gonna get drunk, or you’re gonna get depressed, or you’re gonna go surfing, he’s less likely to be interested in returning to the group than if he sees that we are using the experiences he has provided to grow … If he feels he’s become healthier and his bandmates haven’t, then in his mind it becomes, ‘Why should I go back into a situation that’s risky?’ If the situation is just deteriorating—and I’m not suggesting that’s what’s happening, all right?—then he’s less likely to—”

“What

are

you suggesting then?” Lars shot back.

“I’m suggesting that he would benefit from knowing that we’re on it.”

“So, in other words, lie to him.”

Lars, more than the others, was irritated at the prospect of changing his behavior to suit a rehabbed James Hetfield. Lars saw himself as someone who could maintain a modicum of self-control amid the chaos of Metallica. Why should he be penalized because someone else didn’t have the discipline to know when to say no? “I’ve already told them down at the [treatment facility] that I will respect James and help him and so on,” he said, but added that he would not be “held accountable” if James fell off the wagon.

The title of our first film,

Brother’s Keeper

, was an allusion to the famous Bible story of Cain and Abel. Cain kills his brother, Abel, and when God asks Cain what has happened to Abel, he responds, “Am I my brother’s keeper?” In our film, it’s not clear whether Delbert has killed his brother, but that ambiguity makes you confront the idea of familial responsibility: Did Delbert put his brother out of his misery, and, if so, was that a transgression of society’s laws or an obligation that transcends society’s laws? It’s a tricky concept, this idea of family ties—so tricky, in that case, that the State of New York looked at the Wards’ literal closeness (Delbert and his brother shared a bed) and decided, ludicrously, this was a case of incest gone bad, a crime of forbidden passion. Lars and James aren’t brothers, but they may as well be. Lars, in his unwillingness to change, was raising a corollary to the Ward dilemma: If I live my life independently

of my brother, and he destroys himself as a result of my independence, is there blood on my hands? Am I my brother’s enabler?

“Getting information from a flight’s black box” was the metaphor that Phil employed to sum up the situation with James. Ensconced in a rehab facility, issuing occasional dispatches on his progress or sending information through emissaries of his choosing, James was calling the shots regarding his condition, eventual recovery, and potential return to Metallica. And it pissed off the other guys. As they saw it, even in his absence, James had found a way to make Metallica fall in line behind him. Without saying anything, he was still making them adapt to him.

This resentment complicated their efforts to rethink their relationships with James and one another in the positive way that Phil urged. There’s a scene in

Monster

where we see Kirk telling the others about his recent meeting with James. (As he so often did, Kirk once again found himself in the role of band mediator.) Through Kirk, the others learn that James feels that Lars is putting pressure on him, and that James can’t bring himself to deal with anyone associated with the business side of Metallica, including Bob. Kirk passes on that last bit of news almost apologetically, because in the absence of James, Bob—who, after all, had worked on every Metallica album from the last ten years—had really started to seem like a member of the band, as conflicted, concerned, and confused by James’s absence as Lars and Kirk. Not to mention that Bob, as a working producer and not a full member of Metallica, was put in the position of juggling his professional life to try and stay available at any moment, should James reemerge.

One thing that didn’t make it into

Monster

was Lars’s aggrieved response to what Kirk was telling them: “I don’t think there’s anyone in this room who does not want him to have as much time as possible.” He paused, collecting his thoughts and picking up steam. “I don’t particularly have an issue with waiting six months or a year, but my problem is with how he communicates this to the rest of us. I think that has been completely [overlooked]. From what you are saying, there is nothing that indicates any understanding of this. [He can] take solace behind ‘I need this and I need that’ and ‘It’s a control issue’ and all this horseshit. [But] if it’s established that at any time, he can just go and hide behind ‘I just need this for myself, and fuck everybody else,’ than we’re right back

where we’ve always been, which is [dealing with] his irresponsibility and lack of respect for other people. And that is what I wish would be addressed.” Lars had slim hopes that James would confront these personality issues: “I’m skeptical of it happening on all fronts.”

It turned out that Lars was unwittingly being a little unfair. We all learned, months later when James returned, that he really had been working on bettering himself. But Lars’s sense of rage and frustration reveals two things about what the “surviving” members of Metallica were going through during this period. First, it shows just how little information they had about the status of their comrade. Word on James’s condition would occasionally reach them, but in general there really was a news blackout. That lack of information is key to the second important point Lars’s exasperation revealed: they all loved James very much and felt betrayed by being cut off from him.

Even the ever-patient Kirk eventually learned to rebel against James during this period. One day he announced his plan to go to Hawaii for a week of surfing.

“No,” Lars said sarcastically “we gotta be here and wait.”

“I’m going back to Hawaii,” Kirk replied with a laugh. “And James is gonna be waiting on me for once.”

Phil noted the change. “Kirk really advanced himself today, didn’t he?”

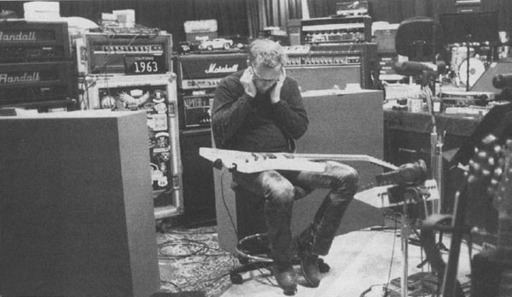

Courtesy of Bob Richman

“Well, James is gonna be waiting on

me

for once,” Kirk repeated. He clearly liked the sound of that.

“A-ha! A little hostility”, Phil said. “‘I’m going away because …’”

“I’m gonna fucking surf, and fuck everyone else!”

Yet, despite all the rancorous talk about James, the rest of Metallica never stopped being protective of his privacy. When discussions about James started to veer too much into the specifics of his problems (or what little they knew about the specifics), they would begin speaking in code or stop talking in front of us altogether. It was Phil who was more willing to tackle the subject of James’s struggles with the cameras rolling. The others often bristled when Phil raised the subject, even obliquely. One day, Phil suggested they talk about the difference between alcoholism and “other addictions.”

“Do we have to go there right now?” Bob asked, cutting him off.

As mad as they were at James, Lars, Kirk, and Bob never wavered when it came to protecting his privacy. The strong emotions of these sessions did, however, lead to the guys bringing up things about James that he probably would not be thrilled about them discussing. For example, James likes to cultivate a sort of working-class “Joe Six-pack” persona, a chronic source of irritation to the more urbane Lars. Lars said he hoped that rehab would soften some of James more retrograde tendencies, including his penchant for Confederate imagery and motorcycles.

Considering James’s all-for-one rule prohibiting extra-Metallica musical collaborations, as well as his documented distaste for hip-hop, the one musical project the rest of Metallica completed during his absence seemed like a bold declaration of independence. The hip-hop producer Swizz Beatz was interested in using some of Metallica’s music for his debut solo album,

Swizz Beatz Presents G.H.E.T.T.O. Stories.

In August 2001, Swizz went to the Presidio studio to meet with Bob, who played him some of the material Metallica had been working on prior to James’s departure. Swizz wound up choosing parts from two separate songs, and edited them together to form a head-bouncing groove for the verse and some loud power chords for the chorus. Lars and Kirk showed up later in the day and everyone discussed possible rappers to perform on the track. They settled on either DMX or Ja Rule. DMX was unavailable, but Ja Rule was interested in appearing on the song, which Swizz had named “We Did It Again.”

Six weeks later, Swizz and Ja Rule showed up at a New York studio. Bruce was there to film the session. Ja Rule brought along an entourage of about fifteen people, who gambled away tens of thousands of dollars playing dice and

smoked enormous blunts. (There was so much pot smoke blowing around that Bruce caught a contact high.) At the same time, I was in an L.A. recording studio, filming Kirk, Lars, and Bob. Both sessions were linked via a computer hookup. The Metallica guys decided Kirk should lay down a guitar solo long distance. The idea was for Ja Rule to ad-lib over the solo. He asked Lars to remind him of some of the lyrics James had been singing on the parts Swizz chose. “‘Nevermore the whipping boy,’” Lars responded.

Ja Rule laughed. “I think I’ll let James handle that one.”

The longer James was away and the more Metallica’s future looked bleak, the more Metallica’s immediate past seemed to take on, for these guys, a rosy glow. The Presidio sessions acquired an almost mythic aura. The music made during those first few weeks became, in the minds of Metallica, more awesome and ass-kickingly great than ever.

“I remember we used to be over at the Presidio every day,” Lars said one day. “We’d have a drink and then we’d play music and listen to it.”

“And we’d get so happy” Kirk said.

“How fun was that?”

“We’d be so happy” Kirk repeated.

“We’d do a song in the afternoon, and then do one after dinner,” Bob chimed in. “This is the other thing that is just fucking staggering: Do you realize that with the other albums we’ve done, after we’d spent as much time on them as we’ve spent at the Presidio, we’d maybe have [settled on] a drum sound. Now, we’ve got, like, how many songs? Twenty?”

“What do you think that means?” Phil wondered.

“That we’re doing something right,” Kirk replied.

Bob nodded. “We’re doing something right.”

“And if you guys are doing something right, it means you gotta carry that belief forward,” Phil said.

“Absolutely,” Bob said.

“Something is brilliant,” Phil continued. “And listening to you guys talk in the last fifteen minutes, you sound like you’re hopefully recharging your batteries a little bit and enjoying reminiscing about what’s happened so far. It makes it clear that we have a greater obligation to what’s already been created. We can’t let it sit and die an unnatural death.”

“No way” Kirk said. “Over my fucking dead body”

The time in the Presidio was now the best time of their lives, the wonder years, the point when the band’s collective artistic ability reached its apex. The fond recollections sparked by James’s absence were, I think, a reaction to the pervasive realization that those days were gone forever and that the longer James stayed away, the more those days started to look like Metallica’s last stand. The band’s decision to dismantle the Presidio studio really intensified the nostalgia. If the worst was to happen, and Metallica was no more, it was comforting for Kirk and James—and even Bob—to imagine that Metallica had disintegrated while at the peak of its powers.

Indeed, it was Bob who sounded the most plaintive note about the Presidio, possibly because, as producer, he was sort of lord of the manor. “The Presidio is disappearing,” he said one day in therapy, as they discussed the closing of their temporary makeshift studio. “That’s a sad thing to me. I even feel bad that I’m part of the process of actually disassembling it. That was such a happy, wonderful place up until this all happened. Now I’m basically going to tear it apart…. And I would say that it’s going to be pretty silly for you guys to hang on to the Presidio, okay? Because this isn’t gonna be over in two months. It’s just not. I mean, that’s my opinion.”