Metallica: This Monster Lives (25 page)

Read Metallica: This Monster Lives Online

Authors: Joe Berlinger,Greg Milner

Tags: #Music, #Genres & Styles, #Rock

Besides his implicit blessing to continue, I was impressed that Cliff went out of his way to reassure us that management had no interest in telling us how to construct our movie. I was also impressed that Cliff was urging us to make the therapy material more meaningful, even as his managerial side worried that such footage might be damaging to the band’s image if not handled properly While I don’t think he’d admit it to himself, much less to us, I think the film

buff in Cliff (he even knew which episode of

Homicide

I had directed) subconsciously saw an interesting filming opportunity that might just push this project to another level.

The execs at Elektra who saw the trailer were less charitable. They wanted it recut so that it included no therapy whatsoever. We handed over a tape of selects from which we had culled the final version of the trailer, and Elektra hired someone else to cut a new version, which we saw a few weeks later. As we expected, without the therapy the project looked a lot less interesting. It hurt to see what was shaping up to be a very unique project watered down into something more ordinary, but part of me was pleased: there was

no way

anyone was going to be interested in airing this. Elektra was basically sabotaging its own efforts to get even a useful promo piece, which bought us a little time to get everyone more comfortable with the idea of us filming therapy. I asked the Q Prime guys to trust us, assuring them that therapy would not be all we had, that ultimately it would be one narrative thread among many. As with all our films, I was hoping against hope that those threads would emerge.

Meanwhile, it looked like we were still in business—that is, if Metallica was. There were rumblings in the Metallica camp that James’s return was imminent. It had been nearly a year since I’d guiltily hoped that something bad would happen to Metallica to liven up our film. Now I was hoping for something good—for the sake of the film, obviously, but also because, like Phil, I found myself really pulling for these guys. As Bruce and I walked out of Q Prime’s building into the sensory overload of Times Square, I thought about the last line of dialogue on our trailer, courtesy of Lars: “I don’t know how the fuck it’s gonna play out.”

CHAPTER 14

WELCOME HOME

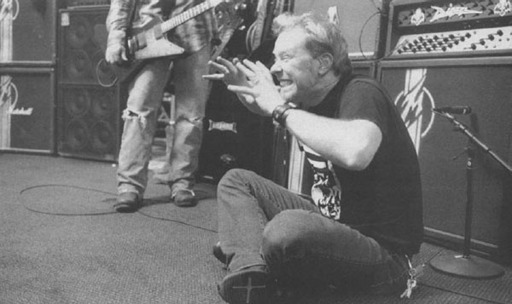

Despite James’s return from rehab, there were still a lot of unresolved tensions. (Courtesy of Bob Richman)

As Bruce notes in this book’s foreword,

Brother’s

Keeper

and the

Paradise Lost

films are about ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances, while

Some Kind of Monster

is about extraordinary people in ordinary circumstances.

This crucial difference influenced our filmmaking methods while making

Monster.

One of the reasons my questions to the Wards are heard in

Brother’s Keeper

is that the brothers’ near illiteracy and thick accents made it difficult to adhere to the verité convention that subjects speak in complete sentences, to downplay the interviewer’s presence. To clarify certain things for the audience, Bruce or I had to augment and explain what the Wards were saying by making our comments audible. Unlike the Wards, whose understanding of the outside world was largely limited to what they saw on TV, James Hetfield is a celebrity, and therefore media savvy. When he returned from rehab, he had a new understanding of the effect a verité Metallica film could have on his life. Our job was to convince him that we did, too.

Bruce and I were in New York in April 2002 when we got a call from Lars. “Hey, Metallica is back in business!” he said. We were ecstatic. We had a quick meeting with the Q Prime managers, who urged us to check in with James to see how he felt about continuing the filming. When we reached James, he was

cordial but distant, so we did our best to be assertive without seeming presumptuous. We told him we wanted to address any concerns he had about the movie, and he replied that he definitely had mixed feelings about continuing to film. Sensing that our project was in danger, Bruce and I took the bold step of suggesting that if we were going to stop shooting and assemble a film with what we had so far, we would need a scene to use as an ending. Why not have us come to San Francisco to film the band watching footage and discussing the film’s future? James sounded wary, but he said yes.

As soon as we hung up, it occurred to us that we should have filmed ourselves speaking with James, and recorded James’s end of the conversation. Our exchange provided exactly the type of moment that warrants a self-reflexive scene. Since he sounded pretty negative about the whole thing, that phone conversation might turn out to be the point at which the fate of this film was decided. Whichever way it turned out, we should have had a camera rolling. Oh well, I figured, at least we’d have an opportunity to film James watching the footage and deciding if he wanted to be filmed some more.

A few days later, Bruce and I were back in San Francisco. With us was Bob Richman, our new director of photography. Bob had shot both

Paradise Lost

films. He was our original choice for the Metallica project, but at the time he thought he had a heart problem that prevented him from working, so we tapped Wolfgang Held, who had shot my Metallica

FanClub

episode. Once we’d begun shooting, Bob discovered that his heart scare was a false alarm. The Metallica project went on longer than Wolfgang expected, so when he told us he wanted to step down, Bob came onboard. Bob’s shooting instincts are amazing, so we were thrilled to have him back.

That Bob’s return to our filmmaking team coincided with James’s return to Metallica was a coincidence.

1

We kind of threw Bob to the wolves. His first day on the job was the day we were trying to convince James that he should let us continue. Metallica had just completed construction of its own recording studio, HQ, an unassuming building in an industrial section of San Rafael, a town in Marin County. When the band was recording at the Presidio, all therapy sessions were held at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel. Now that HQ was open, all of Metallica’s musical and psychological activity would occur under the same roof.

Therapy became more prevalent and more casual. Phil seemed to always be there. They began each day with an hour-long informal chat at a table just off the kitchen. (Hanging over the table was an especially appropriate piece of décor, considering the emotional battles that would soon be fought there: a poster for

Deliverance

, the 1972 film about a group of friends who go camping and find themselves terrorized by locals.) Phil usually stuck around for the rest of the day to monitor Metallica’s writing and recording sessions. Although his near-constant presence erased the clear boundary between therapy and recording, which eventually became a problem, it was easy to understand why he, like us, enjoyed spending time at HQ, his professional commitment notwithstanding. There was a real fun clubhouse atmosphere at the studio. Each band member had his own room (we even had our own production office), there was a Ping-Pong table, a pinball machine, two fully stocked refrigerators (with no alcohol—not so much as a beer), and an overall atmosphere of male bonding. One day when former Marilyn Manson bassist Twiggy Ramirez was hanging around HQ, Phil mentioned how great it was to come to the studio and feel like part of “this family” Lars agreed. “We all go through struggles with our different partners,” he told Twiggy. “We all find that when we come here, we feel better. It’s like, we’re with all these guys who can relate to us. Sometimes we feel like our respective partners aren’t up to speed on this type of connecting.”

On Bob Richman’s first day, as we drove our production van across the Golden Gate Bridge, we discussed the strategy for this very unusual shoot. We had already updated him on the state of Metallica. We told him that today we were going to show Metallica some footage and that James was really on the fence regarding our continued presence. We decided that Bob would hang back at first with the camera off, holding it by his side rather than on his shoulder in a shooting pose. As James (hopefully) relaxed, Bob would gradually insinuate himself into the scene with his camera.

We were the first to arrive at HQ that morning. As we sat in the lounge waiting for the others, I heard James’s voice coming from the tech room in back. He had entered HQ through the rear entrance, which struck me as interesting. I had a sudden twinge of filmmaker’s intuition. I decided we should walk back there and approach him with the camera. James had agreed in our phone conversation to let us film the band meeting on his first day back, so I

was bending the rules a bit by filming him before the meeting, but something told me it was worth the risk.

Bruce stayed behind to capture the other guys as they came in, while I motioned for Bob to follow me.

“Hey, Bob, start the camera.”

“What?”

“Start rolling now.”

“But you said to ease into it.”

“Yeah, I changed my mind.”

As we entered the tech room, we saw Bob Rock giving James a welcome-back hug. As you can see in

Monster,

James was not thrilled when he saw our camera. “Why are we filming this?” he asked with a tight smile on his face.

A lot of things went through my mind at this moment. About a month had gone by since we’d shown our twenty-six-minute trailer to Q Prime. We had scored some points with Metallica’s managers by turning over our footage so that Elektra could recut the trailer, which, as we had expected, was mediocre without the therapy.

The Osbournes

had just debuted and become an overnight sensation. We were already hearing murmurs from Elektra that we might have the next

Osbournes

on our hands. I doubted this would happen—

that therapyless trailer was unlikely to generate much buzz—but it was still one more potential obstacle that stood in the way of us making a great film. Cliff’s feedback on our trailer hadn’t diminished my belief that a great film was possible, but it made me realize that we really had our work cut out for us. On top of all that, James might kill the project on the spot. Despite all these hurdles, we had just turned down USA’s Robert Blake film, which would have been a nice paycheck when I really needed one. So my reflexive response to James’s query, which I thought but thankfully didn’t say, was: “Yeah, why

are

we fucking filming this?”

Courtesy of Bob Richman

What I did say was, “Hey, James, welcome back!” His smile got tighter. Bob instinctively put down his camera, recognizing a hostile subject when he saw one. As if we didn’t have enough working against us on this project, I had now conceivably shot myself in the foot by shooting James too soon.

After Bob Richman cut the camera, I tried to reestablish a level of civility. I pointedly avoided talking about the film, and James seemed to relax a bit. Meanwhile, Phil and the rest of Metallica trickled into HQ. As Bob Richman and I walked back down the hall, I was a wreck, convinced that I’d ruined any possibility of continuing. I also felt guilty about putting Bob in such an awkward position on his first day at work. The camera operator on a verité film has an often thankless job. He or she points the camera at the behest of the director, and if it turns out that camera is aimed at someone who doesn’t appreciate the intrusion, the cameraperson bears much of the brunt of the director’s miscalculations. Besides being a master with the camera, Bob Richman has exactly the sort of comportment you want in a documentary DP: he listens really closely, attunes himself to the mood of any given scene, and has a knack for making himself invisible. I assumed Bob was annoyed right now, but he just chuckled and said, “Well, that certainly worked out great. Good job, Joe.” Bob Rock had told the others about our failed attempt to film James, and they laughed nervously when they saw us. I was positive Bruce was glowering at me, furious that I’d destroyed our project. (Bruce insists to this day that he wasn’t mad at me, so maybe I was just projecting my own guilt onto him.)