Metallica: This Monster Lives (42 page)

Read Metallica: This Monster Lives Online

Authors: Joe Berlinger,Greg Milner

Tags: #Music, #Genres & Styles, #Rock

We rode the elevator in silence.

Bruce and I did a great job of pitching the show during the meeting. The whole time I was talking, I kept thinking, We are actually having a serious conversation about airing these shows in May. We don’t even have the first episode edited. By the rules of the entertainment industry, this is about as fucked up as it gets.

After two hours of discussion, we got up and shook hands. The Showtime guys said they’d get back to us soon. My armpits were really tight again.

During these cold months, Bruce and I traded off between filming in San Francisco and supervising the editing in New York. Whenever I was at our New York office, I willed myself to put on a brave front. The four editors were all pissed at us, thinking this was the most ridiculous assignment they’d ever been given. They had taken to throwing darts at the delivery schedule posted on the

bulletin board. Even as I told them to soldier on, I spent a lot of nights in March unable to sleep, staring at the ceiling, convinced we were headed for a shipwreck. I was starting to think there was no way we could make this happen. By the third week of March, I was practically pleading with Q Prime and Elektra to get Showtime to make a decision and to show the project to other prospective networks. There were so many technical issues that were still unresolved—we didn’t even know how long these shows should be. We were now six weeks away from the show’s supposed debut, and we hadn’t finished one episode.

Finally, Showtime put us out of our misery by passing on the project. It was the best news I’d heard in a long time. “Dodged

that

bullet,” I said to myself as I hung up the phone. Unfortunately, the sense of responsibility that had led me to urge Q Prime to contact other networks now ensured that things were about to get much worse, and that our editors were about to hate us even more. Enter VH1.

I wasn’t surprised to hear that VH1 was interested, even at this absurdly late date. Of course they would jump at this material. VH1 budgets usually max out at about $150,000 per hour, and here we had millions of dollars of some of the most intimate and authentic rock-and-roll footage ever captured. However, it just never occurred to me that anyone involved with Metallica—including Elektra and Q Prime—would actually want this to premiere on VH1, when there were potentially much better opportunities. I didn’t think VH1’s core audience was comprised of Metallica fans. Although Q Prime disagreed with me on that point, I thought we could all agree that VH1’s ratings were unimpressive. I also felt that showing

Monster

on a basic-cable station, interrupted by commercials, cheapened the material. I could talk myself into getting excited about a mini-series on a premium cable channel like Showtime, but the thought of winding up on VH1 with a project of this magnitude (our budget was now five times what we would have gotten for a show that originated with VH1) just made an already dispiriting situation even more demoralizing. VH1 was calling Elektra and Q Prime practically every day, promising round-the-clock promotion and serious rotation of the

St. Anger

music videos. I couldn’t believe it. It looked like this was going to happen. I felt like I had just entered Dante’s fifth ring of hell.

The prospect of shifting gears and turning this into a VH1 series seemed beyond daunting. All the work we’d done over the last few months toward creating six one-hour shows for Showtime, although not worthless, would have to be overhauled entirely. For instance, how would we handle expletives? Our film was full of language that would not be acceptable on a basic cable network

like VH1. (The constant bleeping on

The Osbournes

was part of the show’s campy humor, but did we really want to show the world the “f—” meeting?). We also had to consider frequent commercial breaks. That would dramatically change the length of each episode. Also, a show with commercials needed to be structured differently, to create natural breaks and also to repeat certain crucial information that viewers might forget during commercials. As if this weren’t enough, I almost had to laugh when I heard that VH1 was considering asking us to change the structure of the series to eight half-hour episodes.

There was a selfish element to my desire to make

Monster a

feature film. I fantasized about making a great film as a comeback from my

Blair Witch

debacle. A classy HBO or Showtime series would have been cool, but attaching my name to a hacked-together (because we had no time) basic-cable series could make my reputation as a filmmaker even worse. No matter how good a job we did, I feared that our series would look like just another attempt to cash in on the reality-TV trend. The irony was that we had something much more “real” than any contrived reality show. Ozzy picking up dog shit was nothing compared to James Hetfield picking apart his psyche.

But unlike

Blair Witch 2

, a project that I considered walking away from and probably should have, I couldn’t quit this time. I really had no moral justification; we were merely being asked to deliver what we’d been hired to make. So I bit the bullet even harder, and prepared to take this project to whatever conclusion fate and VH1 dictated.

Oh yeah, we weren’t the only ones struggling to finish a Metallica project. The members of Metallica were, too.

On their first day back in the studio after the Christmas break, the guys took stock of their progress. They had four songs that were almost ready to go—“St. Anger,” “Frantic,” “Dirty Window,” and “Unnamed Feeling”—as well as several in various stages of completion. Everyone was in a buoyant mood. “I realized yesterday that I hadn’t heard the stuff since before Christmas,” Lars said. “What really hit me yesterday afternoon after not hearing it for close to two weeks was just the sonic side of it. I think it plays a big part in how you interpret it. Do you know what I mean? Just the raggedness of it. There’s a lot of energy that comes from that, and that to me is really precious.”

“All the people I play it for have commented on how raw it sounds,” Kirk said. “And how good it feels to hear us playing raw sonics, because the last few albums have been a bit polished.”

James was beaming. “I don’t know if you guys feel this way, but for me this is not like we’re writing songs to put out. This is a product of what we’re doing, hanging out. These are songs that we are going to take with us, like a diary, of this time that we’re having together. That’s what it is. This is for

us.

This is ours and will forever be ours, our memories on CD. There are things that we’re coming up with together and discovering ourselves. During interviews, if someone asks Kirk what a song is about, you don’t have to say, ‘Ask James’ or ‘Ask Lars.’ We all know what it means to us. It’s really cool.”

It was during this period that I realized the music was cohering into a very special document. I could tell that

St. Anger

would be an album of contradictions. Metallica was going “back to basics,” but these were basics that never really existed in the first place—even in the early days, they hadn’t made an album that reflected the equal input of all band members. Not only had Metallica never really made an album that captured the band in a raw, unmediated state (the

Garage Days

records being the exception, and those were all, tellingly, cover tunes)—Metallica had never even really existed in that state.

St. Anger

is the sound of old dogs teaching themselves a trick they didn’t even think to try when they were young dogs. It’s a record meant to sound spontaneous, but it was created in the midst of Metallica’s most self-conscious soul-searching period. Though predicated on the notion of unbridled creativity, much of

St. Anger

was made within the confines of James’s noon-to-four schedule. “There have been eighteen years of just letting the creative energies dictate,” Lars said one day in the studio. To which Bob Rock wisely replied, “Yeah, but there’s been a lot of bodies lying in the ditches because of living that way.”

Of all the people in Metallica’s orbit, Bob knows the most about where the bodies are buried and how they became casualties of Metallica’s artistic process. He began working with Metallica on the Black Album, a time during which Metallica second-guessed every musical decision without aiding one another in making those decisions. “

St. Anger

was the opposite,” Bob says. “The music on the album almost sounds like purging. It doesn’t take the traditional view of what pop music is supposed to sound like. It’s probably the most honest record I’ve ever worked on, in terms of sound. I’m more proud of

St. Anger

than anything else I’ve ever done.” What we captured by documenting the making of

St. Anger

was Metallica coming full circle. As Bob put it to James

one day, in a discussion about lyrics, “It’s easy to say ‘fuck fuck kill kill’; it’s harder to say ‘fuck fuck kill kill’ for a reason.” James picked up the thread: “‘Fuck fuck kill kill and here’s how you dispose of the body’” (He later integrated the line in “All Within My Hands.”) It’s a nice way to look at Metallica’s journey since the Bob came onboard. If the Black Album was about Metallica finding the most rocking way to kill ’em all,

St. Anger

is about the toll all that destruction takes on a human being.

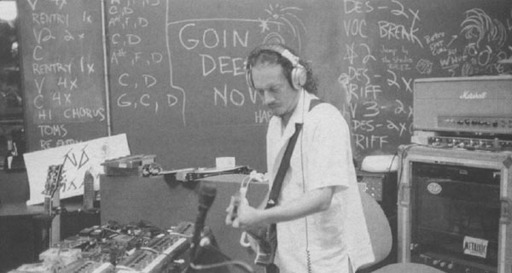

Courtesy of Bob Richman

During the early days of recording at the Presidio, I had found the new music to be less than impressive, the sound of a band consciously avoiding resting on the sound it pioneered but not finding a compelling new direction. Even then, however, there were clues that Metallica was determined to do whatever it took to make this album sound different, including letting the universe issue its cryptic commands. One example: Lars one day accidentally left his snare off the snare drum. Without the rattle a snare produces, the drum sounded like he was pounding on a coffee can. Lars liked the effect and decided to keep the snare off for most of the album.

1

By the end, Metallica emerged with an album that truly sounds like no other mainstream rock album out there.

St. Anger

’s jarring, unorthodox sonics alienated a lot of people, Metallica fans included, and the reviews were decidedly mixed. Bob Rock, who

actually wound up doing some interviews to defend his production decisions, proudly compares the sound of

St. Anger

to Iggy Pop’s infamous

Raw Power

—“which many people say has the worst mix ever,” he says today with a chuckle. “Just recently, I was doing some edits on ‘Some Kind of Monster,’ and I was shocked by how it sounded. It’s just really, really different.”

Raw Power

isn’t the only controversial album

St. Anger

evokes. Lyrically, it’s like a metal version of John Lennon’s

Plastic Ono Band

, released in 1970, soon after the Beatles broke up. Before you reject the analogy as ludicrous (if not blasphemous), consider that Hetfield and Ulrich are to metal what Lennon and McCartney were to, well, pretty much all of rock-and-roll. Both albums document the singers’ painful but necessary transitions between two stages of life, and both albums are informed by therapeutic processes. For Lennon, primal-scream therapy led him to write lines like “I don’t believe in Beatles / I just believe in me.” “Of course the lyrics are crude psychotherapeutic clichés,” the critic Robert Christgau wrote of the album when it was released. “That’s just the point, because they’re also true, and John wants to make clear that right now truth is more important than subtlety, taste, art, or anything else.” You could say the same thing about James Hetfield and

St. Anger

lines like “Do I have the strength to know how I’ll go / Can I find it inside to deal with what I shouldn’t know?”, “Stop to warm at karmas burning,” “I want my anger to be healthy,” and “Hard to see clear / Is it me or is it fear?” Clearly influenced by time spent with Phil and in rehab, these are blunt sentiments driven by intense need, as well as urgent communiqués to everyone who had spent twenty years watching James Hetfield slowly kill himself. Subtlety isn’t the point. As Bob puts it, “James was rebuilding his life and his band. He didn’t have months to work on lyrics.”

2

Bob augmented the naked emotion of James’s lyrics by not doing any of the production tricks that make records sound artificially perfect, such as “correcting” the vocals and making the drums sound uniform. But despite its wartsand-all lo-fi quality, building this monster wasn’t a haphazard process. One more way in which

St. Anger

is paradoxical is that it’s very much a product of modern recording techniques, specifically editing software like Pro Tools. The songs may sound off-the-cuff, but they were painstakingly assembled from hundreds of hours of music. During the same months when we were killing ourselves, trying to turn hundreds of hours of footage into

Some Kind of Monster

, Metallica was trying to construct “Some Kind of Monster” and the rest of

St. Anger

out of hundreds hours of music.