Mind and Emotions (19 page)

Authors: Matthew McKay

“You’ve got to be kidding.”

Donald saw an image of himself taking a deep breath and pausing instead of making a sarcastic remark of his own about Rich. He heard himself continue in a calm voice: “I know I don’t have a good track record on family holidays, but I want this year to be different.”

“I don’t know, Dad.”

“Please just think about it. It would mean a lot to me and to your mother if you came.” Donald imagined ending the call on an amicable note, with his son agreeing to think about it and call him back.

Applications

Learning how to listen and communicate mindfully, make assertive requests, and deal with conflict are particularly useful skills when you’re struggling with anger or depression. Both emotions are typically driven by a sense of helplessness in relationships. These skills can also help with feelings of anxiety, shame, or guilt. These emotions become more bearable if you can effectively communicate them to others, ask for what you want, and say no when you really mean no.

Duration

Learning a particular interpersonal skill like mindful listening won’t take long—maybe just an hour—but applying it is an ongoing process that you’ll engage in for the rest of your life. The more you consciously practice these skills, the more they’ll improve. After a couple of weeks of practice, you’ll notice a difference not only in your relationships, but also in how you experience yourself as you connect with others.

Chapter 11

Imagery-Based Emotion Exposure

What Is It?

Imagery-based emotion exposure uses introspection and visualization to observe, label, and experience your negative feelings in a safe, controlled setting. It’s the reverse of the old habit of avoiding these feelings by suppressing, numbing, or masking them. As you observe your emotions and see how they change and subside, you’ll learn that even the most unpleasant emotions are time limited. As a result, you’ll fear your emotions less and have greater tolerance for negative feelings. Exposure will also change your perception of emotions. Instead of seeing them as catastrophic or overwhelming, you’ll view them as simply unpleasant moments that will soon change.

Imagery-based emotion exposure is a treatment component in all three universal protocols for emotional disorders. In the cognitive behavioral therapy approach, it’s seen as key in helping people overcome emotion avoidance (Allen, McHugh, and Barlow 2008). Dialectical behavior therapy (Linehan 1993) uses it, together with emotion awareness, in emotion regulation training. Acceptance and commitment therapy (Hayes, Strosahl, and Wilson 1999) uses emotion exposure to develop acceptance of painful feelings and to reverse patterns of avoidance.

Why Do It?

There are two main reasons to do imagery-based emotion exposure. First, it will help you gain awareness of your emotional life and learn how emotions actually work. You’ll see, from your own experience, that observing and labeling your feelings supports the natural process whereby they slowly change and dissipate.

The second reason to do imagery-based emotion exposure is to reverse the patterns of avoidance that keep negative emotions going and often intensify them. Exposure leads to acceptance of your feelings and a recognition that they are temporary experiences that will soon morph into something else. Avoidance, on the other hand, stops the natural desensitization process that helps emotions subside, so you end up stuck on a hamster wheel where every burst of emotion frightens you and keeps you running.

Imagery-based emotion exposure targets two transdiagnostic factors: experiential avoidance and emotional masking. Experiential avoidance is one of the main maladaptive coping strategies that drives emotional disorders. When you habitually try to avoid certain negative emotions, you end up drawing your attention to those very emotions and actually making them worse. Emotional masking is the effort to keep anyone from seeing what you feel. But masking feelings, out of either fear or shame, is just another suppression and avoidance strategy. It tends to make painful feelings build and get more intense. And worse, you end up feeling helpless because you can’t tell anyone what’s upsetting you. When you don’t express what you feel, others are unlikely to respond to your pain and offer support.

Imagery-based emotion exposure prepares you to better express your emotions to others. The fear of saying what you feel out loud to someone you care about diminishes as you learn to watch and describe your emotions. Likewise, the shame associated with exposing your inner self also begins to fade as you practice saying what you feel.

What to Do

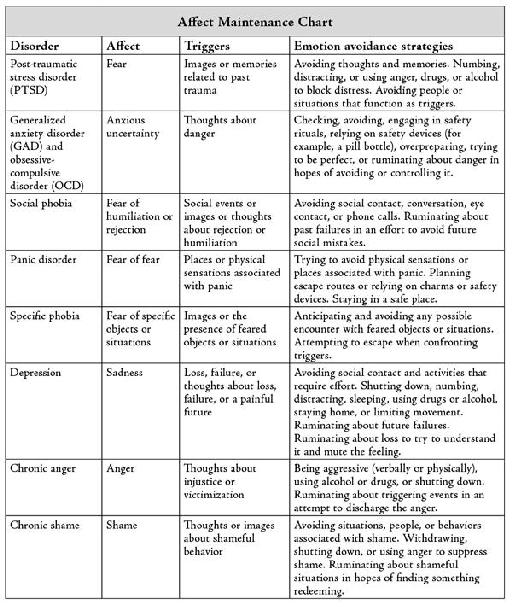

Doing imagery-based emotion exposure requires an understanding of what triggers and maintains the affect for each emotional disorder. (As a reminder, “affect” is the term psychologists use for people’s subjective experience of a feeling, other than bodily sensations.) The following Affect Maintenance Chart summarizes the emotions, triggers, and avoidance strategies typical of various emotional disorders. The left-hand column lists the most common emotional disorders. The second column indicates the primary affect associated with each disorder. The third column identifies the kinds of situations, thoughts, and images that can set off the emotion. These are the types of thoughts and visualizations you’ll use to evoke emotions for exposure purposes. The right-hand column lists the ways you might try to block, numb, or somehow get away from the affect. Here’s a key point: During exposure exercises, you shouldn’t engage in these or any other emotion avoidance strategies.

Though it’s tempting to think otherwise, emotion triggers aren’t what create emotional disorders. Your life is full of thoughts, memories, and experiences that evoke feelings. This is normal and healthy. Emotional disorders are created by the emotion avoidance strategies that interrupt the normal wave of an emotional experience as it rises, crests, and recedes. Avoidance strategies prevent habituation, the process of getting used to painful experiences so they’re no longer upsetting you. If emotions are allowed to take their course, they pass. Even very painful emotions surge and then diminish as you habituate to them naturally. But if you use emotion avoidance strategies, your painful feelings are briefly suppressed, only to roar back as strong as ever. And they keep coming back because they are never fully experienced and allowed to run their course.

Let’s take the experience of sadness as an example. A loss or perhaps a failure triggers the original emotion. Later, merely a memory or thought about the original event can be a trigger for sadness. But what turns a period of sadness into chronic depression is avoidance. People start avoiding social activities, and almost any activity that involves effort. That’s because, initially, these activities make them feel worse—more sad and tired. People also try to numb their sadness with TV, video games, drinking, overeating, overindulging in other substances, or passive behavior. They spend a lot of time on the couch or in bed, trying not to feel anything. The result is that the sadness never gets a chance to resolve and pass, and the avoidance and inactivity only serve to prolong and deepen the feeling, until it becomes chronic.

Anxiety disorders are also maintained by emotion avoidance strategies. Efforts to stop or get away from anxiety only prevent habituation, so you never desensitize to what scares you. Whether you cope by checking, avoiding, worrying, escaping, staying in safe places or with safe people, trying to prevent scary body sensations, or using alcohol, charms, or safety devices, the result is that you get stuck in fear. That’s because it’s always blocked and interrupted before your body and mind get a chance to habituate and let the fear naturally subside.

Enhancing Your Emotion Awareness

An important first step before practicing imagery-based emotion exposure is training yourself to be more aware of your emotions. This is an extension of the work you did in chapter 2, The Nature of Emotions, when you recalled emotion-laden images or listened to emotionally evocative music and recorded your experience on the Emotional Response Worksheet. Now we’re going to take it to the next level. In this exercise, you’ll not only name the emotion, but describe it with as much detail and nuance as possible. To help you find words for your feelings, read through the following Emotion Thesaurus. It will give you a broad range of terms to help you identify the subtle distinctions among feelings.

The Emotion Thesaurus

Anger:

agitated, angry, annoyed, bitter, contemptuous, disgusted, disturbed, enraged, exasperated, frustrated, grumpy, hostile, irritated, mad, outraged, resentful

Depression:

anguished, bored, broken, crushed, defeated, dejected, despairing, disappointed, disgusted, dismayed, distraught, disturbed, empty, exhausted, fragile, grieving, hopeless, hurt, lonely, miserable, sad, sorry, tired, vulnerable, worthless

Fear and anxiety:

afraid, anxious, apprehensive, edgy, frightened, horrified, hysterical, jumpy, nervous, panicky, restless, tense, terrified, uneasy, unsure, worried

Happiness and joy:

blessed, blissful, bubbly, cheerful, content, delighted, eager, energetic, enthusiastic, excited, exhilarated, glad, happy, hopeful, joyful, lively, loved, pleased, proud, relieved, satisfied, thrilled, worthy

Shame and guilt:

apologetic, ashamed, embarrassed, foolish, guilty, humiliated, insulted, mortified, regretful, shy, sorry

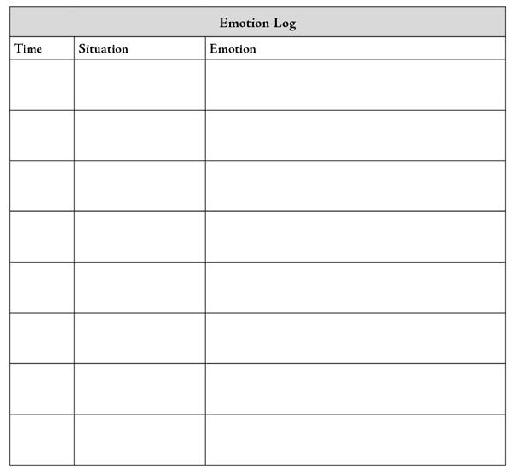

To practice describing your feelings, use the following Emotion Log to record your feelings over the next week, describing each emotion you experience as fully as possible. Record the time and situation, then, under “Emotion,” start with a main word to label the feeling. Then expand on your description, using the Emotion Thesaurus to find as many other related words as seem to apply. Make your description as nuanced as possible.

Make copies of the worksheet and try to keep one with you at all times, leaving the version in the book blank so you can make more copies as needed. If possible, make notes in the Emotion Log four times a day: before breakfast, before lunch, before dinner, and before bedtime. That way you’re likely to recall more of your emotions. Remember, try to go beyond a simple word or phrase and give as rich a description as possible.

Mindfully Observing Emotions

A second important step before practicing imagery-based emotion exposure is to practice mindfully watching your emotions. Over the next week, devote fifteen or twenty minutes a day to mindfully observing your feeling state. If you’ve forgotten the basics of mindfulness, reread chapter 5, Mindfulness and Emotion Awareness, before doing this exercise. There are five simple but challenging rules you should follow while mindfully watching your feelings:

- Observe and label.

Watch the experience, as if from a little distance, and use one or two words to mentally label the feeling. - Don’t judge the emotion.

Try to accept the feeling for what it is: one of many emotions you’ll have today, and just one of a multitude you’ll have over your lifetime. If you have evaluative thoughts about yourself or your feeling, notice them and try to let them go. - Don’t block or resist your emotion.

Don’t try to argue yourself out of it or push the feeling away. If possible, avoid trying to distract yourself from the feeling. Just let yourself have it, for however long it lasts. - Don’t amplify, hold on to, or analyze your emotion.

Try not to get enmeshed in thinking about a feeling, figuring out where it came from, justifying it, explaining it, or attaching great importance to it. Just let it be at whatever level or intensity it naturally reaches. Try to watch it with detachment, rather than imbuing it with great significance. - Watch, don’t act.

You can notice your action urges, but don’t let them spur you into behavior. Observe your impulses with detachment and acceptance; they’re just part of your feeling and don’t require you to do anything.