Mind and Emotions (16 page)

Authors: Matthew McKay

32. _______________ When I’m upset, I lose control over my behavior.

33. _______________ When I’m upset, I have difficulty thinking about anything else.

34. _______________ When I’m upset, I take time to figure out what I’m really feeling.

35. _______________ When I’m upset, it takes me a long time to feel better.

36. _______________ When I’m upset, my emotions feel overwhelming.

(Copyright 2004 by Kim L. Gratz, Ph.D., and Lizabeth Roemer, Ph.D. Used with permission.)

Scoring: Put a minus sign in front of your rating numbers for these items: 1, 2, 6, 7, 8, 10, 17, 20, 22, 24, and 34. Then sum up all your ratings, adding the positives and subtracting the negatives, and write the result here: _______________.

This number represents how much your upsetting feelings are affecting your life today, at this moment. Compare it with the total from the first time you did this exercise, at the end of chapter 1. If your score is now lower, that’s great. It means you’re making progress and are ready to start working on the skills in the rest of the book.

If today’s score is the same or higher, that’s okay too. It just means you have to ask yourself, “Did I take my time in the first half of the book, carefully doing the exercises, following the instructions, and continuing to practice and use the skills I learned?” If you can honestly answer, “Yes, I did,” then go on to the next chapter.

If your answer is more like “Well, I kind of skimmed through some parts,” then you probably need to go back and review some of the earlier treatment chapters, especially those addressing transdiagnostic factors. If you’re a little hazy on what we mean by “transdiagnostic factors,” that’s another sign that you should go back for a little review, in this case to the chapter on the nature of emotions.

Up to this point in the book, we’ve presented five treatment chapters that teach skills you can learn and practice mostly in the privacy of your own home, and even your own mind. From here on, we get into skills that will eventually require you to do things out in the real world, often in interactions with others. It’s a little scary, but the best, most important and powerful skills are yet to come.

Chapter 9

Doing the Opposite

What Is It?

Doing the opposite is a valuable skill that is as easy to understand as it is difficult to accomplish: Whatever your painful emotions normally urge you to do,

do the opposite

. For example, when you feel painfully shy and want to be quiet and retiring, instead you smile, make eye contact, and speak up in a clear, firm voice.

Doing the opposite doesn’t make you a phony or invalidate your feelings. Your feelings—all of them—are legitimate and valid. But you can choose not to act on them. You can choose to change emotion-driven behaviors that have been damaging your relationships or keeping you from accomplishing important things in life. Opposite action is a way of regulating your feelings, not denying them. It’s a way of acknowledging your experience but choosing new behavior to modulate or change what you feel.

In repeated studies, Marsha Linehan, founder of dialectical behavior therapy, discovered that giving in to action urges leads to more emotional intensity, not less (Linehan 1993). Psychologist David Barlow adapted Linehan’s strategy of doing the opposite for use in his unified cognitive behavioral protocol and also reported that while emotion-driven behavior might relieve bad feelings in the short run, it intensifies them over time (Moses and Barlow 2006; Allen, McHugh, and Barlow, 2008).

Why Do It?

Doing the same things you’ve been doing in response to painful feelings usually intensifies those feelings. For example, acting on anger with loud accusations might feel good for a moment, but in the long run it damages relationships and leads to more anger, not less. And turning down invitations and staying home when you’re depressed will tend to make you more depressed, not less.

On the other hand, acting contrary to your emotional urges tends to decrease the intensity of emotions. When you feel angry but respond by acknowledging the other person’s point of view and speaking in a normal tone of voice, you short-circuit your anger cycle. If you overcome your depressive withdrawal by maintaining eye contact, asking questions, and acting interested in a conversation, it’s likely to lift your mood.

Doing the opposite directly targets the transdiagnostic factor experiential avoidance, the coping strategy in which you try to avoid painful feelings by avoiding certain situations and activities. Since the situation or activity that you’re avoiding is almost always something you need to do or face in order to feel better, doing the opposite is just what the doctor ordered.

Doing the opposite also addresses a second transdiagnostic factor: response persistence, which is the tendency to cope with stress in the same way, over and over, even if it doesn’t work. Doing the opposite encourages you to act in new ways in the face of difficult emotions, rather than continuing to rely on the same old habitual responses.

What to Do

Before you can start doing the opposite, you need to identify the painful emotions you want to work on and what you typically do in response. In this context, the simple word “do” has far-reaching implications: what you touch or pick up or put down, how you hold your body, where you look or don’t look, what you say or don’t say, the words you choose, and your tone of voice. So, before we move on to exercises to help you start doing the opposite, we want to give you a bit of background on the forms emotion-driven behavior tends to take, and emotion communicators—the ways people tend to express their emotional state during emotion-driven behavior.

Emotion-Driven Behavior

Negative emotions have a tendency to make you do the same thing over and over in an attempt to make the bad feelings go away. The trouble with emotion-driven behavior is that, not only does it fail to make bad feelings go away, it usually intensifies the bad feelings.

If you’re depressed, the emotion drives you to shut down and withdraw repeatedly. In every domain of your life—at home, at school, at work, with friends, with family—you’ll tend to be inactive and nonresponsive. You won’t participate in what’s going on around you, go out, or initiate conversations. It’s easy to get trapped in a vicious cycle in which the more you shut down and withdraw, the more depressed you feel.

If you feel angry most of the time, the emotion drives you to aggressive behavior. You’ll be quick to take offense and short on tolerance. You’ll respond to delays, incompetence, or inconvenience with automatic, explosive, hair-trigger aggression. And contrary to the popular misconception that blowing off steam can be helpful, repeatedly expressing your anger only fuels more anger.

If you’re anxious, the emotion drives you to avoid certain people, situations, experiences, or things. For example, you may seize any excuse to avoid spending time with your boss or your father-in-law. You may hate speaking up in a group situation, or maybe you’d really rather not drive anywhere you haven’t been before, or drive at night, on the freeway, or in certain parts of town. Or perhaps you always avoid heights, elevators, or tight, confining spaces. Unfortunately, avoidance only makes your anxiety worse, not better.

If you’re plagued by guilt and shame, these emotions drive you into hiding, aggression, or defensiveness. You may try not to be noticed by other people and mainly stick to the margins and shadows of life. If you’re caught in the smallest error or inconsistency, you might lash out in anger or become excessively defensive, throwing out a string of explanations and excuses for your mistake. And then you’re likely to feel even more guilty and ashamed.

Emotion Communicators

Emotion communicators are the words, gestures, postures, facial expressions, and tones of voice that communicate how you feel. You may be surprised to learn that words play a relatively small role. Only about 40 percent of your meaning is conveyed by the words you choose. The other 60 percent is conveyed by body language, situation, and tone of voice. That’s why e-mails are so frequently misunderstood: They consist entirely of words, without the body language and tone of voice that convey so much of what people communicate.

Emotion communicators work in two directions: outward to your audience, and inward to yourself. In addition to conveying information to others, your body language and tone of voice also tell

you

how you’re feeling. In this way, your tone, posture, and gestures create a feedback loop that reinforces depression, anxiety, shame, and other mood states.

So when you’re sad, saying, “I’m sad,” is only part of the story. The rest comes across in your quiet tone of voice, downcast eyes, slumped shoulders, shrugs, and grimaces. And when you feel your own posture and hear your own voice, you think, “Wow, I’m really down. I am so depressed,” and this deepens your depression further.

When someone is angry, it’s not so much the insults and curses that frighten people. It’s the yelling, the raised fist, the frowning, the red face, and so on. And all of those nonverbal cues are also telling the angry person, “Jeez, look how pissed off I am. I’m really furious,” which heightens and prolongs the rage.

If being on a high floor in a hotel makes you anxious, you might tell the clerk who offers you a room on the thirty-fifth floor, “I don’t think so.” The words themselves are pretty neutral. Your nervousness will be conveyed by the tremor in your voice, the widened eyes, the glancing upward, how you pull your elbows closer to your sides, and the slight protective hunch of your shoulders. And as these bodily cues feed back to you, you tell yourself, “Look how terrified I am by just the thought of the thirty-fifth floor,” and your fear increases.

Guilt or shame might lead a shopper to blurt out, “I’m sorry,” and leave a store before completing a purchase. Again, the words themselves are conventional and almost meaningless in casual conversation. However, the clerk will pick up on the shopper’s feelings of shame and inadequacy through the ingratiating smile that doesn’t match the frowning eyebrows, the wringing of the hands, the falling or sobbing cadence of the voice, the turning away, and the abrupt departure. These emotion communicators will also tell the shopper, “Oh, no! I’m so ashamed I can’t even function like a normal person.”

Unpacking Emotional Expression

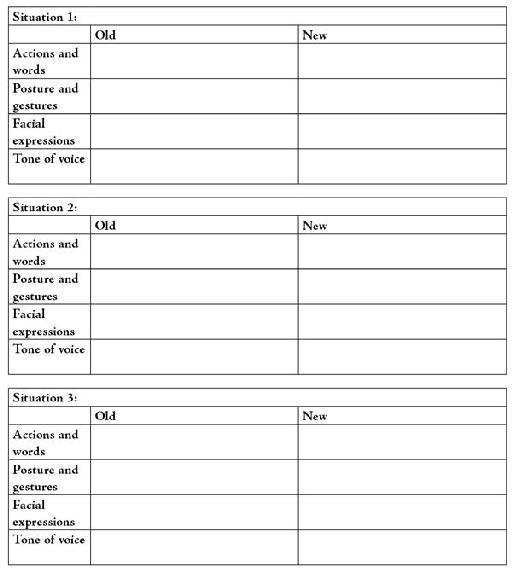

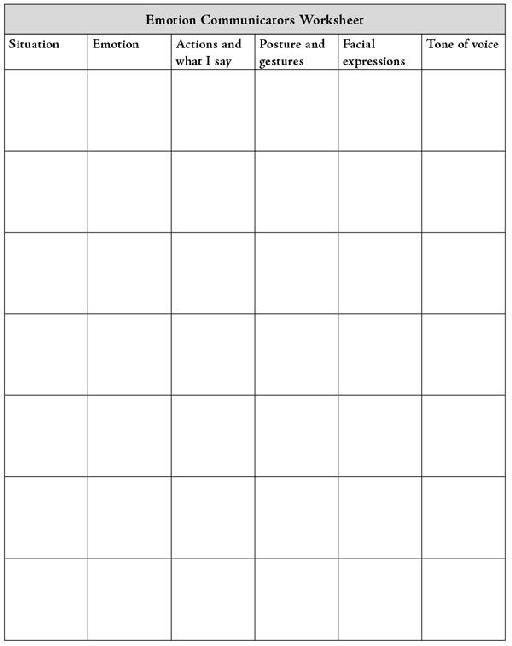

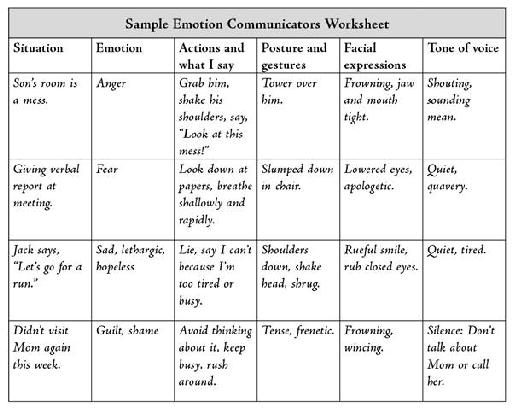

The worksheet that follows will help you explore the details of what you do in challenging situations that tend to provoke emotion-driven behavior. It unpacks emotional expression into four key components: actions (including what you say), posture and gestures, facial expressions, and tone of voice. Use the worksheet to analyze, in detail, your emotional expression in three or four situations in which you experience painful feelings. When thinking about which difficult situations to analyze here, choose situations that occur frequently in your life, that result in emotion-driven behavior that has negative consequences for you, and that happen predictably, in circumstances you can plan for. After the blank worksheet, we’ve provided a sample worksheet that combines responses from several different people. You may want to copy the worksheet and leave the version in the book blank for working with other challenging situations in the future.

Planning to Do the Opposite

Now that you’ve broken down some typical responses into concrete details, this exercise will help you plan the specifics of how you’ll do the opposite in terms of actions and words, posture and gestures, facial expressions, and tone of voice. Again, we’ve provided samples after the blank worksheet. You may want to copy the worksheet and leave the version in the book blank for working with doing the opposite in other situations in the future.