Mind and Emotions (11 page)

Authors: Matthew McKay

The first problem is that trying to dispute and replace a negative thought with one that’s positive implies that the negative thought is false and the positive one is more accurate. Couching things in this true-false dichotomy may not always serve people well. In fact, assuming that negative thoughts are distorted sometimes pushes people to defend them all the more (McKay, Davis, and Fanning 2007).

The second problem is that disputing negative thoughts in the middle of a distressing situation can function as an avoidance strategy—an effort to stop painful emotions—and there’s a lot of evidence that trying to block or avoid painful emotions actually makes them more intense and longer lasting. So in the long run, disputing thoughts while you’re upset might only make the upset worse (Allen, McHugh, and Barlow 2008). David Barlow, one of the leading lights in cognitive behavioral therapy, now suggests that cognitive restructuring be done before or perhaps after an upsetting event, not during the event (Allen, McHugh, and Barlow 2008). This way you aren’t trying to suppress emotions during situations that provoke strong feelings.

In light of the above research, plus evidence that disputing thoughts doesn’t always work (Hayes 2005), the cognitive flexibility training presented here takes a different approach from classic cognitive behavioral techniques. It encourages an awareness of multiple alternative interpretations for events and discourages seeing thoughts as right (positive) or wrong (negative). The more ways you can look at something, the less tied you’ll be to any particular negative thought. It also differs in that it encourages you to broaden your thinking either before or after events that trigger strong emotions, not during such events.

Cognitive flexibility training isn’t about trying to argue with or dispute negative thoughts. It also isn’t about trying to suppress or control thoughts or avoiding emotions as they arise by banishing problematic ideas. It’s about developing multiple ways to look at things that happen to you and exploring alternatives to old negative appraisals.

Why Do It?

Negative appraisals contribute to anxiety, depression, anger, shame, and guilt. Virtually every painful emotion can be intensified and maintained by such thoughts. Although these thoughts are a result of your mind doing its best to prepare you for danger and help you face difficult things in life, the bias toward seeing the negative has a huge cost: You end up thinking that every horror story your mind tells you is true. The world you live in becomes what your mind makes it: scary, sad, or unfair. And you see yourself not as you are, but as the person your mind describes: lazy, bad, selfish, or stupid.

Cognitive flexibility training can loosen the way your mind defines reality. As you learn to develop multiple alternative appraisals, you’ll be less inclined to automatically accept everything your mind tells you as truth. Your new appraisals may not be any more right (or wrong) than your old thoughts, but by virtue of the fact that they are new possibilities, they help stretch your mind and loosen old, rigid beliefs.

What to Do

The first step in cognitive flexibility training is to identify what type of thinking you’re doing. In this section, we’ll help you learn to recognize the five types of negative appraisals, then provide exercises that will help you understand and change each of these thinking patterns.

Recognizing Categories of Negative Appraisal

As mentioned, there are five types of negative appraisals: negative predictions, underestimating the ability to cope, focusing on the negative, negative attributions, and shoulds. It’s important to learn to recognize which of these categories your thoughts fall into, because different cognitive flexibility techniques are effective for each. To help you learn to identify them, here are some example thoughts from each category:

NEGATIVE PREDICTIONS

- I’m going to end up losing my house.

- My boss is going to give me a bad review.

- This heartburn will turn out to be an ulcer.

UNDERESTIMATING THE ABILITY TO COPE

- I’m no good at interviewing; I can’t deal with looking for work.

- I’d be destroyed if my mother died.

- I couldn’t stand it if they were upset with me.

FOCUSING ON THE NEGATIVE

- This vacation is boring.

- Every time we visit my brother, he monopolizes the conversation and spoils the evening.

- My life is nothing but problems.

NEGATIVE ATTRIBUTION

- My sister didn’t come to Thanksgiving because she doesn’t like my girlfriend.

- He’s listening to the ball game because he’s tired of talking to me.

- She was late because she’s mad at me.

SHOULDS

- He should help me and not wait for me to ask.

- I should be making more money at this point in my life.

- I was stupid to buy this car; I should have bought a newer one.

Now we’d like you to practice identifying which of these five categories a particular thought belongs in. Read through the list of negative appraisals below, and in the blank, mark each according to the category it falls into:

a. Negative predictions

b. Underestimating the ability to cope

c. Focusing on the negative

d. Negative attributions

e. Shoulds

1. _______d_______

Example:

He didn’t call because he’s losing interest.

2. _______________ I should be married with a family.

3. _______________ I’m not going to pass the course.

4. _______________ My son’s behavior problems are too much for me.

5. _______________ My son’s going to get kicked out of school.

6. _______________ What a lousy day off—a total loss.

7. _______________ My husband was quiet at dinner because he didn’t want to eat out.

8. _______________ I can’t handle another medical problem.

9. _______________ People shouldn’t talk about their family issues.

10. ______________The whole course was a waste.

11. ______________ I ought to read good books instead of trash.

12. ______________ My friend is calling because she wants something.

ANSWER KEY:

2: e; 3: a; 4: b; 5: a; 6: c; 7: d; 8: b; 9: e; 10: c; 11: e; 12: d.

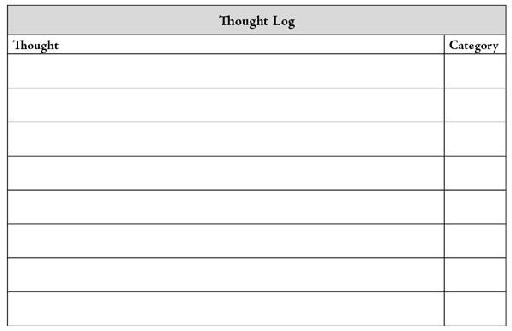

Keeping a Thought Log

To strengthen your skill at recognizing categories of negative appraisals, keep a thought log for the next week. Each time you have a painful emotion, write down the thoughts that accompanied this feeling, then note which category of appraisal this thought reflects. Make several copies of the form below to last through the week, and use the same letter designations as in the previous exercise:

a. Negative predictions

b. Underestimating the ability to cope

c. Focusing on the negative

d. Negative attributions

e. Shoulds

At the end of the week, review your log and note which types of appraisals occur most often. Then spend some time thinking about the emotional impact of these thoughts and what, if anything, you do to cope with or respond to them.

The sections that follow provide exercises targeting each type of negative appraisal. You may find it helpful to read through all of them, but you can focus your efforts on the exercises that target your most typical or frequent types of negative appraisals.

Cognitive Flexibility with Negative Predictions

The key to cognitive flexibility is developing the ability to come up with multiple ideas about how to interpret an event or situation. With negative predictions there are several ways to go about this. Two of the following exercises will help you assess how accurate your negative predictions are, and the third will help you figure out what purpose these predictions serve.

Calculating the Validity Quotient

The validity quotient is a measure that gives you an idea of how accurate thoughts are at fortune-telling. To find the validity quotient for a specific prediction, start by answering the following questions (Moses and Barlow 2006):

How many times have you made this prediction in the past five years?

How many times in the past five years has it come true?

To calculate the validity quotient, divide the number of predictions that came true by the total number of predictions. You can also use the validity quotient to assess the accuracy of predictions in general. How many negative predictions have you made, of all types, in the past year? How many turned into realities?

Here’s an example: June kept having anxious thoughts that whomever she was dating at the time would leave her. She estimated that over the past five years she’d worried about this at least 100 times. During the same time period, June herself left several relationships, and one ended by mutual agreement. Her validity quotient was 0/100. June used this analysis to recognize that although her thoughts predicting rejection felt very believable at the time, they were just ideas—and not in the least bit accurate. Far from being certain to happen, they had actually never happened.

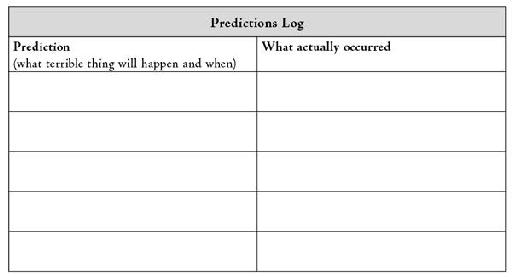

Keeping a Predictions Log

In the previous exercise you looked at the accuracy of past predictions. This exercise will help you track the accuracy of predictions as they occur. Every time you seriously start to worry about something and imagine a bad or painful outcome, use the following Predictions Log to record exactly what you fear will happen and when. From time to time, check your Predictions Log and bring it up to date. Did the predicted catastrophe happen or not? In the right-hand column, write the actual outcome of each prediction. You may want to make copies of the log and leave the following version blank so that you can always make more copies as needed.

The Predictions Log will help ease the sense of certainty that so often accompanies negative predictions based on worries. And when these thoughts seem less absolute, they’ll trigger less fear.

Here’s how it worked for Annie. She began keeping a Predictions Log focused primarily on her fears about her six-year-old daughter. Annie wrote down all of her worst-case predictions about medical problems, relationships with other children, and learning and behavior problems. In the space of three months, Annie logged more than two dozen negative predictions. Yet only one of them came true (a lice infestation during a classroom epidemic). As a result of keeping her log, Annie began to take her worries a little less seriously. She started viewing them as possibilities, rather than likely outcomes. Annie’s worries felt softer, less absolute, and less scary.

Finding the Purpose of Your Predictions

Every behavior has a purpose, and that includes mental behaviors—your thoughts. In this exercise, you’ll identify the functions of your negative predictions and gain an understanding of why you keep turning to them. Look back at some of the predictions noted in your Predictions Log or try to recall some negative predictions from the past few weeks. These thoughts are all trying to do one thing: reduce uncertainty. They seek to prepare you for bad things that might happen and somehow keep you safe.

But is this working? Think back and notice what happens when you make negative predictions. Do you feel more secure and more prepared for danger, or are you simply more scared?

For most people, negative predictions leave them feeling more anxious and less safe. In fact, the degree of anxiety people experience is often proportional to the time they spend focusing on predicting. So here’s what you can do: When your mind generates scary predictions, ask yourself, “Is this working for me? Is this helping me deal with an uncertain future, or just frightening me more?” If the answer is the latter, remind yourself that these are just thoughts, not reality. Label your thoughts, saying something like “There I go again with the predictions (or what-ifs or future thoughts).” This will help you notice your thoughts but take them less seriously.