Mind and Emotions (7 page)

Authors: Matthew McKay

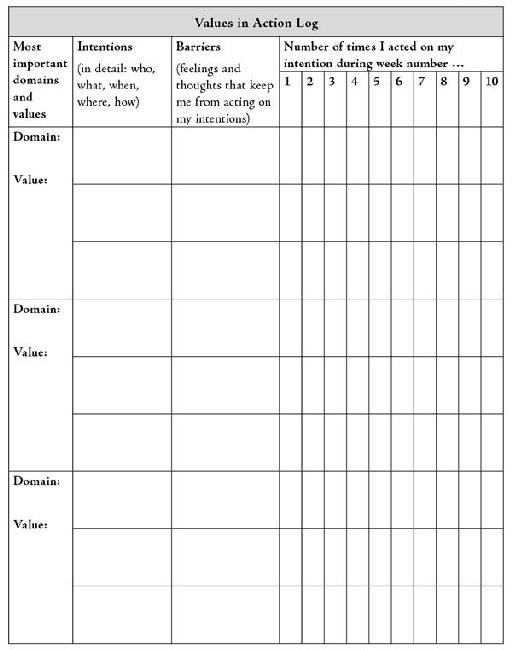

Use the following log to work on your most important two or three domains from the previous exercise over the next ten weeks. In the first column, write your most important domains and the core value you identified for each.

Then, in the second column, write your intentions: the things that you’d be doing if you could get past all the painful thoughts and feelings that keep you from acting 100 percent according to your values. Avoid vague, general intentions like “Be more loving” or “Stay calm.” For the purposes of this exercise, describe small, discreet, measurable actions:

- What you will do exactly: actions and words

- Whom you will do this with

- Where and in what situation you will do it

- When you will do it

Next, visualize yourself doing each of your intentions. Close your eyes and really imagine what it would be like, using all your senses: see yourself and any other people, watch what you do, hear the sounds, smell the smells, feel temperature and textures. Imagine what will be running through your mind and what will be happening in your body. Concentrate on the thoughts and feelings that will be barriers and tend to stop you from following through on your intention. When you have a good sense of the typical barriers to each intention, write them in the “Barriers” column.

Finally, commit to putting your values and intentions into action. Use the log to record the number of times you acted on each of your intentions each week. At the end of ten weeks, you’ll have a record of how you did.

Here’s a blank worksheet for your use, followed by an example filled out by Phil. We recommend that you continue using the log for other values and intentions in the future, so make several copies and leave the version in the book blank for future use.

Planning Committed Actions

Steve Hayes, father of acceptance and commitment therapy, frequently uses the metaphor of a bus to illustrate how committed action works (Hayes, Strosahl, and Wilson 1999; Hayes 2005). Here’s our version of that metaphor: Imagine that you’re driving a bus called Your Life. On the front of the bus is a sign saying where the bus is headed. The sign is a value, like “Being a loving person” or “Doing what I say I’m going to do.” When you turn the bus in the direction of your values, painful emotions and thoughts often pop up in front of you like monsters, and you can’t get around them or run over them. You could stop the bus and wait for them to go away, and that’s exactly what you do every time you put valued actions on hold because of difficult emotions. Unfortunately, those monsters don’t go away, so your bus is stalled by the side of the road.

The solution? You have to let the monsters on the bus and take them along for the ride. They’ll continue to try to cause trouble, yelling from the back of the bus that the route you’re taking is too dangerous, scary, dumb, hard, and so on. That’s what monsters do. That’s their job. Your job is to keep driving the bus in the direction you’ve chosen.

Committed action requires willingness on your part to feel some painful emotions in service of your values. Your values are your motivation. Focusing on the destination posted on the front of your bus takes your attention off of painful feelings. It makes them a little more tolerable and, in time, helps quiet the noisy rabble in the back of the bus.

So, where to start? One way is to pick the easiest, least threatening domain and start there. It’s like climbing smaller mountains before tackling Mount Everest. However, since your strongest, most important value will also be your most powerful motivator, you can make an argument for starting at Everest. It’s up to you and your sense of your own values and motivation.

In whatever domain you choose to make your first committed action, do some careful planning first. Take some time to think about concrete goals: specific actions you can perform, in a series of small, manageable steps, at certain times, in certain places, and with particular people. It helps to plan your action in the format below.

In service of my value of _______________

I am willing to feel _______________

so that I can _______________,

in these steps:

1. _______________

2. _______________

3. _______________

Here’s an example of an action plan:

In service of my value of

caring and compassion for my friends

,

I am willing to feel

nervous and anxious

so that I can

drive on the freeway and bridge to visit Marianne in the hospital

,

in these steps:

1.

Monday 7 p.m., call Marianne and tell her I’ll visit on Wednesday morning.

2.

Tuesday after class, gas up car, clean windows, get change for toll, mark map.

3.

Wednesday 10 a.m., drive to the hospital and have a great time visiting.

Applications

Values clarification helps with chronic anger by taking your attention away from the outrage of the moment and focusing it on where you really want to go in life. This will prevent you from falling into another cycle of confrontation, recrimination, remorse, and resentment. For example, at work you could plan to honor your values of productivity and teamwork by soliciting and accepting your assistant’s suggestions rather than calling her incompetent and insisting that she do everything your way.

Making step-by-step plans based on your values will lift depression by getting you into action. Instead of eating ice cream in front of the TV on Thursday nights, you can live up to your value of community service by attending and participating in that Rotary committee meeting you’ve been blowing off for the last six months.

Likewise, your values can motivate you to stop avoiding situations that make you anxious. For example, if you value self-expression, creativity, and community involvement, you’ll be motivated to practice performing a song and to sign up for the town talent show.

Getting in touch with your long-term, enduring values will also help you get beyond feelings of shame and guilt. For example, if you value truthfulness and standing up for the underdog, this will motivate you to speak up at a city council meeting to oppose an ordinance that makes it tough on homeless people in your town.

Duration

You can identify your values in a matter of hours, and then begin committing to valued actions right away. Use the ten-week log to track your follow-through, and after the first ten weeks, reassess your values and begin a new ten-week log. In a few months, putting your values into action will become more automatic and you won’t need the log.

As the habit of following through on valued intentions develops over months and years, you’ll start to allow emotions to flow through you (rather than obstructing you) as you ask yourself, “What’s really important to me in this situation? What do my values say I should be doing here?”

From time to time, it’s a good idea to revisit your values. Over time, you form new relationships, take on new responsibilities, encounter new health and career challenges, acquire new knowledge and interests, and so on. Your values will evolve with time, becoming deeper, more complex, and more mature. You should reassess your values every few years as your life changes.

Chapter 5

Mindfulness and Emotion Awareness

What Is It?

Mindfulness has two key aspects. First, it is the nonjudgmental awareness of what is. It is seeing without interpreting, evaluating, or appraising. It is the experience of everything that goes on around you without thoughts about value or worth.

Second, mindfulness is focused attention on the present moment, rather than the future or the past. It is seeing, hearing, and feeling what’s happening now, not getting caught up in what-if thoughts about possible catastrophes in the future or regretful thoughts about losses and mistakes that have already occurred. Mindfulness is attention to the river of now: your ongoing experience of what’s happening in your mind, your body, and the environment that surrounds you.

Mindfulness, with a specific focus on emotion awareness, is a component of all three universal protocols for treating emotional disorders: dialectical behavior therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, and acceptance and commitment therapy.

Why Do It?

Focusing on the future or the past intensifies painful emotions. What-if thoughts about the future make us anxious. Judgmental and regretful thoughts about the past can trigger depression, shame, or guilt. Shoulds—thoughts that focus on what we or others should have done differently—create anger or depression.

Staying in the present moment is an antidote to future- and past-oriented thoughts that can get you in trouble emotionally. That’s why mindfulness exercises are an essential part of the management of painful affect.

Mindfulness targets two of the transdiagnostic factors that lie at the root of emotional disorders: the maladaptive coping strategies of rumination and experiential avoidance. Because rumination is almost exclusively focused on the future or the past, mindfulness of the present moment reduces ruminative thinking. It’s hard to be consumed with what-ifs and judgmental thoughts if you’re focused on what your senses tell you in the here and now.

Mindfulness addresses experiential avoidance by allowing you to observe the way emotions rise, crest, and slowly diminish. Rather than avoiding the emotion, you can watch it, from the first uncomfortable feelings to the tail end, when that particular emotion morphs into other experiences. Watching the emotion mindfully is a huge shift from maladaptive coping strategies that involve trying to numb or suppress it. Now you can see it for what it is: a feeling that has a brief life on the stage of your experience and then fades away.

Mindfulness is crucial to emotion regulation for another reason too. It helps you see your emotions as only one part of the present moment. Whether you’re happy, angry, sad, or whatever, the emotion is just a single aspect of your current experience. There are so many other pieces of the present moment, including what you see, what you hear, what’s happening in your body, and what you’re tasting, smelling, and touching. Emotions are important, but they’re not your total experience. Mindfulness helps you observe your emotions and situate them in the context of everything else.

What to Do

In this section, you’ll find a series of exercises that will help you increase your awareness of the present moment. All of them facilitate shifting from a painful focus on the future or the past to an awareness of the here and now. This moment can be a refuge, a location to recover from some of the dark places your mind takes you, so let’s begin.

Inner-Outer Shuttle

This exercise is a good introduction to mindfulness because it teaches you to differentiate between things happening inside your body and experiences in the outside world.

Start by closing your eyes and taking a deep breath. Next, notice any sensations inside your body. Observe any pleasant feelings. Also notice the locus of any pain or tension, but don’t let your mind linger there. Are there other sensations, like pressure, heat, or cold? Notice your breath. Be aware of the sensations in your feet where they touch the floor and in your hips if you’re sitting.

After a minute or two of looking inside, open your eyes and shift your attention to what you see, hear, and smell, as well as feelings of texture or temperature. Just move from one sense mode to another. Look at the shapes and colors around you, then let yourself be aware of small, ambient sounds, like a clock ticking. Also notice sounds that may be coming from outside the room or building. Do you hear the hum of a refrigerator, heater, or air-conditioning?

After a minute or two of external focus, close your eyes and return to an internal focus. Try to notice other, perhaps more subtle sensations than you did before. Let your attention roam throughout your body, noticing what you feel. Once again, if there’s anything uncomfortable or painful, notice it in the context of all other sensations and move on to whatever else there is to be aware of. After a minute or two, open your eyes and switch to outer awareness one more time.