Mind and Emotions (12 page)

Authors: Matthew McKay

Cognitive Flexibility with Assessing Your Ability to Cope

How would you cope if the worst happened? You may have images of collapsing or being emotionally overwhelmed. Your mind may be saying, “I couldn’t stand it if what I fear actually happened.” Or your mind might serve up a global sense of catastrophe and a vague feeling that you couldn’t take it. The best way to deal with thoughts such as these is to draw up a plan for coping with your worst-case scenario, as in the first exercise below. You may also find it helpful to review how well you’ve coped with difficulties in the past, and the second exercise will help you do just that.

Drafting a Worst-Case Coping Plan

Start by assuming that your worst-case prediction has come true. Imagine facing cancer, a lost job, the end of your relationship, or whatever catastrophe you fear. Imagine that you’re in the middle of the crisis trying to grapple with the event. On the Coping Plan Worksheet that follows, write a brief description of your worst-case prediction. Since you may want to generate additional coping plans in the future, use a copy of the worksheet and leave the version in the book blank for future use.

Now shift your attention to what you’d do to cope, using the following questions to help you generate a plan. Start by considering how you’d cope behaviorally and writing your ideas in the “Behavioral coping” section. What, specifically, would you do to face this crisis? If it was a medical problem, what steps would you take to get treatment, negotiate accommodations at work, or secure support at home? If you were facing an end-of-life crisis, how would you deal with financial affairs, the emotional needs of your family, and limitations as your physical capacities decline? If you fear a financial crisis, outline the steps you’d take to reduce expenses, secure a source of funds, or change your living situation. As you think about how you’d cope behaviorally, also consider what values would guide your choices in the situation. If you feel uncertain about this, refer back to chapter 4, Values in Action.

Next, think about how you’d cope emotionally and record your ideas in the “Emotional coping” section. What could you do to deal with the emotional fallout from the crisis? Think about some of the skills you’ve learned in this book. At this point, mindfulness skills would probably be most effective. Later in the book you’ll learn other skills that will also be helpful, such as self-soothing, doing the opposite, and emotion exposure. As you learn more skills, be sure to integrate them into your coping plans.

Next, turn to the section “Cognitive coping.” Would mindfulness, defusion, or any of the techniques in this chapter help you face your feared scenario?

Finally, move to the section “Interpersonal coping.” Are there friends, family members, or others who might offer support if the feared event occurred? Later, in chapter 10, Interpersonal Effectiveness, you’ll learn other skills that might be helpful here, such as making assertive requests or saying no. Again, be sure to incorporate these into future coping plans. Here’s the blank worksheet for you to copy, followed by a sample.

Coping Plan Worksheet

Worst-case prediction:

_______________

Behavioral coping:

_______________

_______________

_______________

_______________

Emotional coping:

_______________

_______________

_______________

_______________

Cognitive coping:

_______________

_______________

_______________

_______________

Interpersonal coping:

_______________

_______________

_______________

_______________

Now that you’ve come up with a comprehensive coping plan, have your feelings regarding your worst-case prediction changed in any way? Has your fear level gone up or down? Does the scenario seem less overwhelming or less scary to think about?

Here’s an example filled out by Anthony, who had an enduring worry that his marriage was in trouble. He and his wife were in couples therapy, but the sessions only seemed to stir up more conflict. He feared they were headed for divorce, and didn’t know how he’d cope if that happened. (Note that Anthony’s plan makes use of some strategies that you’ll learn in later chapters.)

Anthony’s Coping Plan Worksheet

Worst-case prediction:

She calls it quits, says she’s got a lawyer, and is getting a divorce.

Behavioral coping:

Get my own lawyer.

Try to explain things to my daughter, Jeanie, so she isn’t scared.

Work out a temporary custody schedule.

Look for a two-bedroom apartment so Jeanie can have her own room when she’s with me.

Emotional coping:

Learn to accept the emotion using exposure techniques.

Spend some time in a beautiful place—Yosemite?

Get support from friends. Do fun things with Jeanie. Get back into photography.

Cognitive coping:

Remember that I have a plan.

Try to find positives in my new life.

Try to accept that we’re different people with different needs, and that we’ve been growing

apart for years.

Interpersonal coping:

Turn my anger into assertive requests regarding assets and time

with Jeanie.

After completing the worksheet, Anthony was surprised to discover that he felt less anxious. He still wanted to save his marriage, but having a plan for coping reduced his panic and sense of being overwhelmed when he thought about the possibility of divorce.

Remembering Your Coping History

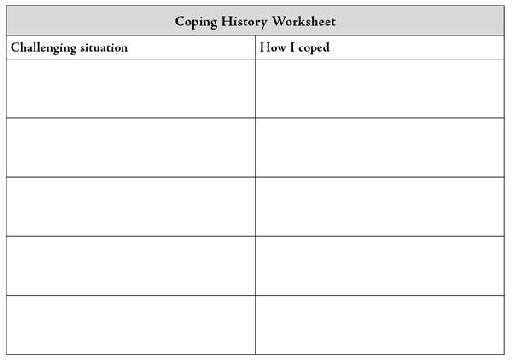

You’ll probably find it helpful to remember that you’ve faced difficult situations in the past and coped with them successfully. Use the following Coping History Worksheet to list five major challenges in the past where you coped more effectively than expected. For each crisis, note the specific ways you coped. Did you do anything that surprised you or seemed different from your usual response to challenges? Are there common threads across these situations in terms of ways you responded effectively?

When Rena, a forty-five-year-old social worker who struggled with self-esteem, examined five challenges she’d dealt with successfully, she noticed that a common thread was assertively asking for what she wanted. She hadn’t let people push her around, as she often did. It was illuminating for Rena to see that she was capable of standing up for herself and did actually possess effective coping skills—she just had to use them.

Cognitive Flexibility with Focusing on the Negative

Focusing on the negative is perhaps the most problematic cognitive habit for maintaining depression. Fortunately, it can be overcome with a few specific skills. One key is to expand your focus and take a different perspective. The first two exercises will help you do that. You may also find it helpful to consider the purpose these negative thoughts serve and how well they’re working for you; the third exercise addresses this.

Using Big-Picture Awareness

Focusing on the negative is like eating dinner and only noticing the food you don’t like. As for the rest of the meal—what you might have enjoyed—you simply don’t pay attention. Negative focus shows up in countless ways. Whether you’re thinking about a vacation, a conversation, a movie, a relationship, a job, a place you lived, or how you’re going to spend tomorrow, focusing on the negative turns it into something dark and sad. You simply fail to notice, remember, or anticipate anything that feels good.

Stepping back and taking a look at the big picture is a way to overcome this cognitive habit. It’s simple to do. After you’ve said or noticed what you don’t like about an experience, add some positive assessments to help balance your perspective. For each negative appraisal, acknowledge two things that you liked or appreciated. Make it a rule not to think or talk about the negative without identifying two positive aspects. When looking for the positive, consider these categories:

- Physical pleasure or comfort

- Positive emotions

- Rest, relaxation, relief, or peace

- A sense of satisfaction, accomplishment, or validation

- Finding something interesting, exciting, or fun

- Learning something

- The feeling of connection or closeness

- The feeling of being loved or appreciated

- Finding something meaningful or valued

- The feeling of giving something

Put these categories on an index card and keep them with you. Then, when you think or speak negatively about something, use these categories to find two positive aspects and balance your perspective.

There’s nothing inherently wrong with having negative thoughts and evaluations, and they may, in fact, be true. But there are always positives in every event and situation, and ignoring them puts you on a one-way street to painful emotions.

For example, Leah hated visiting her mother-in-law. And worse, her complaints about it and reluctance to visit were creating conflict in her marriage. So she decided to try this exercise. When she looked at the list of positive categories, she was surprised to see that several applied: Her mother-in-law served delicious pastries, so visiting often offered some physical pleasure. Leah had fun playing with her in-laws’ collie, and she actually felt a sense of connection with her mother-in-law when they talked about a TV program they both enjoyed.

Looking at the big picture allows you to see that things aren’t all good or all bad. Most experiences have multiple components; some feel good, and some don’t. Seeing each event as an amalgam of the pleasant and unpleasant helps you develop more balanced and flexible thinking.

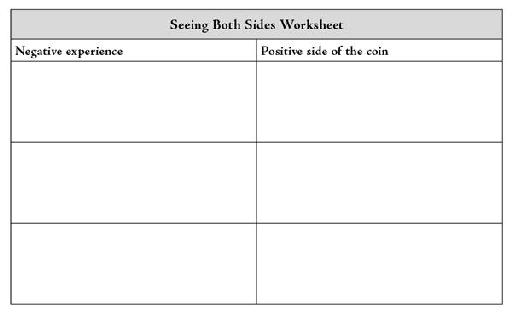

Seeing Both Sides of the Coin

Nearly every bad or painful thing that happens has embedded in it the exact opposite. Most losses include something gained or learned. Moments of failure and weakness often evoke strength or determination. Right alongside trauma, there’s often an incredible will to survive.

Like most people, you’ve probably experienced many painful moments, losses, and disappointments. Yet if you look, most of these experiences offer something else. The coin has another side. Although a negative focus may keep you from seeing the other side (the positive), it’s usually there. Cognitive flexibility training encourages you to look past the pain and recognize the positive qualities or outcomes usually embedded in even the worst of times. As with the exercise Using Big-Picture Awareness, the positive aspects often show up in specific categories, such as the following:

- Learning something

- Finding new strength or determination

- Gaining greater appreciation of the struggles of others

- Experiencing greater acceptance and an ability to let go

- Discovering new or unrecognized parts of yourself

- Finding love and support you hadn’t known were there

- Gaining confidence in your ability to cope, face things, and survive

- Developing a deeper sense of values and what matters most to you

Try it right now. Below, list three events that seem to be entirely negative, such as serious losses or failures on your part. You’re well acquainted with how painful they were, but now flip the coin over and look for the positive aspects. You can use the categories above or come up with your own characterizations.

Shana used this exercise to look back at the six miserable years she spent in psychology grad school. She’d been depressed beyond belief and almost quit numerous times. But when she looked for the positives, she found there were quite a few: finding unwavering support from her best friend, developing a new sense of willpower and perseverance, learning how to take better care of her body, and discovering a commitment to help others in pain.