Mind and Emotions (23 page)

Authors: Matthew McKay

Now take some time to carefully work out your own situational emotion exposure hierarchy. Again, make copies and leave the version in the book blank so you can use it for future situational exposure hierarchies.

Practicing Situational Emotion Exposure

Now that you’ve created your exposure hierarchy, you’re ready to start doing exposures. The procedure for situational emotion exposure is similar to what we outlined in chapter 12, Interoceptive Emotion Exposure:

- Start with the least threatening situation on your hierarchy.

- Place yourself in that situation.

- Focus on the uncomfortable emotion that you’re working on.

- Notice how the feeling shows up in your body.

- Use the scale of 0 to 10 to continuously rate your level of distress as it rises and falls.

- Stay in the situation for at least 60 seconds. Don’t retreat from the situation or do anything to distract or distance yourself.

- Remain in the situation until your level of distress drops several points, indicating that you’re experiencing some desensitization. For an exposure that’s very brief by nature, you may not have time to observe your level of distress declining. In that case, just go on to the next step and repeat the exposure until your distress level is 2 or 3.

- Practice repeated exposures to the situation until your level of distress ends up at a tolerable level of 2 or 3. Don’t wait too long between exposures. An ideal schedule would be to practice one or two exposures a day.

- Then go on to the next situation in your hierarchy and work through it using the same process. Continue in this way until you’ve mastered all of the items on your hierarchy.

Once you’ve completed your first hierarchy, you can construct a new hierarchy to work on another area of emotional avoidance.

When you practice situational exposure, you’ll generally find that anxiety or any other painful feeling tends to come on like a wave, building rapidly in intensity and then slowly subsiding and receding. Your goal isn’t to reduce your distress level to 0 in each situation, but to experience each situation over and over until the wave of emotion is smaller and more tolerable—more like a knee-high wave at the beach, not a huge breaker that could knock you off your feet.

In order to more quickly experience the desensitization effect of situational emotion exposure, it’s important to keep focused on the particular uncomfortable emotion you’re working on. Notice shifts in the emotion’s intensity and any subtle ways it might be changing. Above all, consciously resist emotion-driven behavior. Don’t permit yourself to engage in any form of avoidance or withdrawal. This includes subtle things like closing or unfocusing your eyes, thinking about something else, shutting down, or numbing. If you’re working on confronting situations that provoke anger, don’t respond with aggressive words, postures, or actions.

In the 1970s and 1980s, when cognitive psychologists were working out the best way to do situational emotion exposure, many therapists had their clients do relaxation exercises before, during, and after practicing an exposure. People were also instructed to prepare what therapists termed “stress coping thoughts” or affirmations to repeat to themselves during an exposure. More recent opinion is that these strategies aren’t helpful, and that they may, in fact, constitute a subtle form of avoidance that delays the desensitization effect of exposure.

You may want to use the following log or something similar to keep track of your distress levels during each exposure exercise. Alternatively, you could just add notes to the hierarchy itself.

Practice your exposure exercises daily, working steadily through your hierarchy. Situational emotion exposure works best when you practice it on a daily basis, without long breaks between exposure sessions. Sylvia started her exposure exercises by calling a friend to arrange to have lunch together at school, and progressively moved forward on her exposure hierarchy until she reached the situation that caused her the highest level of distress: stating her real opinions in class. Even with spring break and midterms, she was able to complete her hierarchy and significantly overcome her social phobia in seven weeks.

Obstacles to Exposure

If you try situational emotion exposure but don’t experience a reduction in your levels of distress, it’s time to become a detective. Look closely at what you’re actually doing in the exposure situations. It may be that you’re somehow avoiding the exposure, either overtly or covertly.

If you postpone experiencing a situation for several days, or if you try it and feel overwhelmed and leave the situation early, before your distress has declined, that’s overt avoidance. If this happens, add some additional, easier steps to your hierarchy so that you start with a less threatening situation. Then follow through, practicing the exposure on schedule and remaining in it long enough to experience some habituation.

Covert avoidance consists of all the subtle cognitive strategies for escaping situations without physically leaving: deep breathing, saying prayers or affirmations, spacing out, entertaining distracting thoughts, visualizing positive outcomes, and so on. Anything that takes your attention away from your feelings in the moment will interfere with effective exposure. When practicing situational emotion exposure, keep asking yourself, “What am I feeling right now? How is it showing up in my body?”

Applications

Although situational emotion exposure was first developed to relieve anxiety, it works equally well for other painful emotions, including anger, shame, guilt, and depression. Let’s look at some short examples illustrating the approach with depression, anger, and shame.

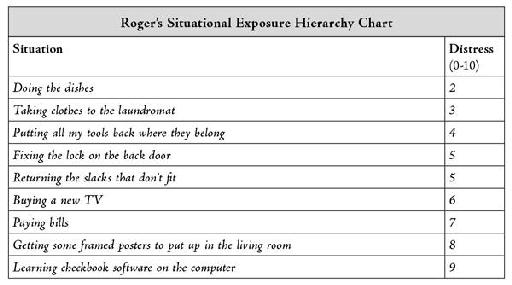

Here’s a hierarchy of situations involving simple daily tasks created by Roger, a carpenter whose depression made him want to collapse on the couch and do nothing after work and on weekends.

For Sophia, her persistent feelings of anger drove her to aggressive outbursts in which she shouted and threw things. She created this hierarchy of situations to practice without giving in to urges to behave aggressively.

Rick’s feelings of shame kept him hiding out and pulling back from life. Here’s the exposure hierarchy he came up with.

People suffering from obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) typically require more prolonged exposure to desensitize to some of their symptoms. For the phobic avoidance symptoms of OCD, for example, fear of germs or harm, extend situational exposure sessions to several minutes, until your distress level goes down to near zero. With PTSD it also works better to extend exposure to stimuli such as crowds or loud noises—stay in the situation until distress levels fully subside.

Duration

Situational emotion exposure works best when you practice at least one exposure session a day and keep moving steadily through your hierarchy. To keep up your momentum, be sure to practice at least three or four times a week. If you have a hierarchy of twenty items and work on it daily, and if each item requires two or three repetitions to become tolerable, you could complete your hierarchy in as little as six weeks, though eight weeks may be more realistic.

Post-treatment Assessment Exercise

Congratulations on completing the treatment chapters of

Mind and Emotion

s. You’ve come a long way, through many ups and downs. You’ve met and mastered many challenges and, we hope, experienced many exciting changes in your life.

Now is the time to take stock and celebrate. Fill out the Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz and Roemer 2004) a third time and compare your score today with your previous scores.

Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS)

Please indicate how often the following statements apply to you by writing the appropriate number from the scale below on the line beside each item.

1. _______________ I am clear about my feelings.

2. _______________ I pay attention to how I feel.

3. _______________ I experience my emotions as overwhelming and out of control.