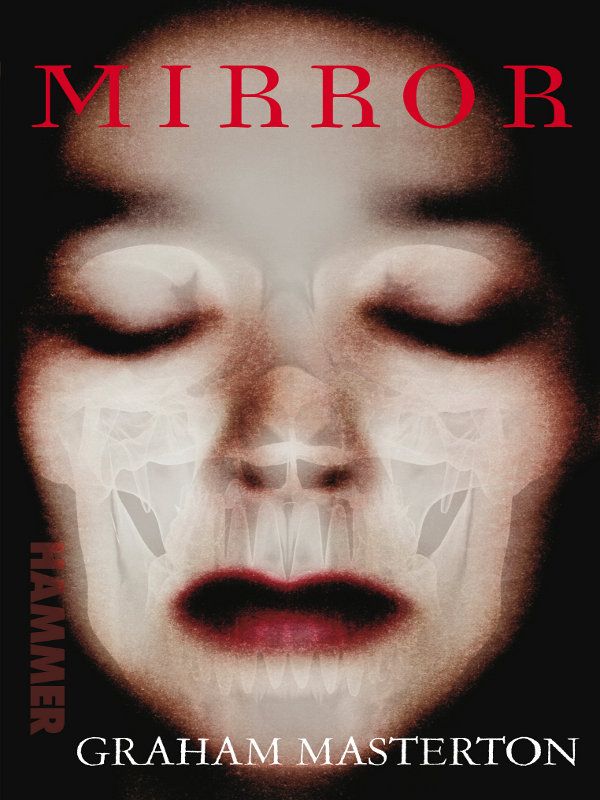

Mirror

Contents

About the Book

It is said that a mirror can trap a person’s soul…

Martin Williams is a broke, two-bit screenwriter living in Hollywood, but when he finds the very mirror that once hung in the house of a murdered 1930s child star, he happily spends all he has on it. He has long obsessed over the tragic story of Boofuls, a beautiful and successful actor who was slaughtered and dismembered by his grandmother.

However, he soon discovers that this dream buy is in fact a living nightmare; the mirror was not only in Boofuls’ house, but witness to the death of this blond-haired and angelic child, which in turn has created a horrific and devastating portal to a hellish parallel universe. So when Martin’s landlord loses his grandson, it is soon apparent that the mirror is responsible.

But if a little boy has gone into the mirror, what on earth is going to come out?

About the Author

Graham Masterton was born in Edinburgh in 1946. After training as a newspaper reporter, Graham went on to edit the new British men’s magazine

Mayfair

. At the age of 24, Graham was appointed executive editor of both

Penthouse

and

Penthouse Forum

magazines.

Graham Masterton’s debut as a horror author began with the wildly popular

The Manitou

in 1976. Altogether Graham has written over a hundred novels, ranging from thrillers and horror to disaster novels and historical sagas, as well as four short story collections.

GRAHAM MASTERTON

À François Truchaud

Merci, mon ami!

One

MORRIS NATHAN LIFTED

his folded sunglasses up in front of his eyes like a lorgnette and watched in satisfaction as his fourth wife circled idly around the pool on her inflatable sunbed. ‘Martin,’ he replied, ‘you should save your energy. Nobody, but nobody, is going to want to make a picture about Boofuls. Why do you think that nobody’s done it already?’

‘Maybe nobody thought of it,’ Martin suggested. ‘Maybe somebody thought of it, but felt that it was too obvious. But it seems like a natural to me. The small golden-haired boy from Idaho state orphanage who became a worldwide star in less than three years.’

‘Oh, sure,’ Morris agreed. ‘And then got himself chopped up into more pieces than a Colonel Sanders Party Bucket.’

Martin put down his drink. ‘Well, yes. But everybody knows that, I mean that’s part of the basic legend, so I haven’t actually shown his death in any kind of graphic detail. You just see him being driven out of the studio that last evening, then fade-out. It’s a bit like

Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid

. You remember the way that ended.’

Morris lowered his sunglasses and squinted at Martin thoughtfully. ‘You know something, Martin? I used to deceive myself that I married for intellect, can you believe that? Conversation, wit, perception – that’s what I wanted in a woman. Or at least, that’s what I

kidded

myself I wanted in a woman. My first three wives were all college graduates. Well, you remember Sherri, don’t you – my third? Who could forget her, I ask? But then one day just after Sherri and I were divorced, I was looking through my photo albums, and I realized that each of my wives had one thing in common that wasn’t anything to do with intellect.’

He turned and looked fondly out at the twenty-nine-year-old titian-haired woman in the tiny crochet bikini circling around and around on the breeze-ruffled surface of the pool.

‘Jugs,’ he said, ‘that’s what I married them for. And I was being a fool to myself for not admitting it. I was like the guy who buys

Playboy

and tells himself he’s buying it for the articles.’ He wiped his mouth with his open hand. ‘It’s infantile, sure. But that’s what I like. Jugs.’

Martin shielded his eyes with his hand and peered out at the woman in the pool. ‘You made a good choice this time, then?’

‘Well, sure. Because Alison has the figure without the brains. If you subtract her IQ from her bra size, you get a factor of eleven. And, believe me, next time I meet a woman I take a shine to, that’s going to be the only statistic I’ll ever want to know.’

Martin paused for a moment before getting back to the subject of Boofuls. He didn’t want Morris to think that he wasn’t interested in Alison, or how small her mind was, or how enormous her breasts. He picked up his vodka-and-orange-juice, and sipped a little, and then set it down on the white cast-iron table.

‘I have the treatment here if you want to read it,’ he said, clearing his throat.

Morris slowly shook his head. ‘It’s poison, Martin. I can’t think of a single producer who isn’t going to hate the idea. It has the mark of Cain. All the sickness of Fatty Arbuckle and Lupe Velez and Sharon Tate. Forget it. Everybody else has.’

‘They still show

Whistlin’ Dixie

on late-night television,’ Martin persisted. ‘Almost anybody you meet can remember at least two lines of “Heartstrings”, even if they don’t know who originally sang it.’

Morris was silent for a long time. A pair of California quail fluttered onto the roof of his Tudor-style pool-house and began to warble and look around for dry-roasted peanuts. Eventually, Morris said, ‘You’re a good writer, Martin. One day you’re going to be a

rich

writer, that’s if you’re lucky. But if you try to tout this particular property around Hollywood, you’re not going to be any kind of writer at all, because nobody is going to want to know you. Just do yourself a favor and forget that Boofuls ever existed.’

‘Come on, Morris, that’s ridiculous. That’s like trying to say that Shirley Temple never existed.’

‘No, it’s not. Shirley Temple wasn’t brutally hacked to death by her grandmother, now, was she?’

Martin rolled up his screenplay into a tight tube and smacked it into the palm of his hand. ‘I don’t know, Morris. It’s something I really want to do. It has absolutely everything. Songs, dancing, a sentimental story line.’

Alison had paddled herself to the side of the pool and was climbing out. Morris watched her with benign possessiveness, his sun-reddened hands clasped over his belly like Buddha. ‘Isn’t she something?’ he asked the world.

Martin nodded to Alison and said, ‘How’re you doing?’

Alison reached out and shook his hand and sprinkled water all over his shirt and his screenplay. ‘I’m fine, thanks. But I think my nose is going to peel. What do you think?’

‘You should use sunscreen, my petal,’ said Morris.

Alison was quite pretty in a vacant sort of way. Snub nose, with freckles. Pale green eyes. Wide, orthodontically immaculate smile. And really enormous breasts, each one as big as her head, barely contained in her crochet bikini top. By quick reckoning Martin worked out that her IQ was 29, give or take an inch.

‘Are you staying for lunch?’ Alison asked him. ‘We only have fruit and yogurt. You know – my figure and Morry’s tum-tum.’

Martin shook his head. ‘I only came over to show Morris my new screenplay.’

Alison giggled and leaned forward to kiss Morris on his furrowed scarlet forehead. ‘I hope he liked it, he’s been

so-o-o

grouchy today.’

‘Well, no,’ said Martin, ‘as a matter of fact he hated it.’

‘Oh,

Morry

,’ Alison pouted.

Morris let out a leaky, exasperated sigh. ‘Martin has written a screenplay about Boofuls.’

Alison made a face of childish disgust. ‘Boofuls? No wonder Morry hated it. That’s so

icky

. You mean a horror picture?’

‘Not a horror picture,’ Martin replied, trying to be patient. ‘A musical, based on his life. I was going to leave out what happened to him in the end.’

‘But how can you do that?’ asked Alison innocently. ‘I mean, when you say “Boofuls”, that’s all that anybody ever remembers. You know – what happened to him in the end.’

Morris shrugged at Martin as if that conclusively proved his point. If a girl as dumb as Alison thought that it was icky to write a screenplay about Boofuls, then what was Paramount going to think about it? Or M-G-M, where Boofuls had been shooting his last, unfinished picture on the day he was murdered?

Martin finished his drink and stood up. ‘I guess I’d better go. I still have that

A-Team

rewrite to finish.’

Morris eased himself back on his sunbed, and Alison perched herself on his big hairy thigh.

‘Listen,’ said Morris, ‘I can’t stop you trying to sell that idea. But my advice is, don’t. It won’t do you any good and it’ll probably do you a whole lot of harm. If you do try, though, you don’t bring my name into it. You understand?’

‘Sure, Morris,’ said Martin, deliberately keeping his voice flat. ‘I understand. Thanks for your valuable time.’

He left the poolside and walked across the freshly watered lawn to the rear gate. His sun-faded bronze Mustang was parked under a eucalyptus just outside. He tossed the screenplay onto the passenger seat, climbed in, and started the engine.

‘Morris Nathan, arbiter of taste,’ he said out loud as he backed noisily into Mulholland Drive. ‘God save us from agents, and all their works.’

On the way back to his apartment on Franklin Avenue he played the sound track from Boofuls’ last musical,

Sunshine Serenade

, on his car stereo, with the volume turned all the way up. He stopped at the traffic signals at the end of Mulholland, and two sun-freckled teenage girls on bicycles stared at him curiously and giggled. The sweeping strings of the M-G-M Studio Orchestra and the piping voice of Boofuls singing ‘Sweep up Your Broken Sunbeams’ were hardly the kind of in-car entertainment that anybody would have expected from a thin, bespectacled thirty-four-year-old in a faded checkered shirt and stone-washed jeans.

‘Shall we dance?’ one of them teased him. He gave her a tight smile and shook his head. He was still sore at Morris for having squashed his Boofuls concept so completely. When he thought of some of the dumb, tasteless ideas that Morris had come up with, Martin couldn’t even begin to understand why he had regarded Boofuls as such a hoodoo. They’d made movies about James Dean, for God’s sake; and Patricia Neal’s stroke; and Helter Skelter; and Teddy Kennedy’s bone cancer. I mean, that was

taste

? What was so off-putting about Boofuls?

He turned off Sunset with a squeal of balding tires. He parked in the street because his landlord, Mr Capelli, always liked to garage his ten-year-old Lincoln every night, in case somebody scratched it, or lime pollen fell on it, or a passing bird had the temerity to spatter it with half-digested seeds. Martin called the Lincoln ‘the Mafiamobile’, but not to Mr Capelli’s face.