Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power (20 page)

Read Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power Online

Authors: Robert D. Kaplan

Tags: #Geopolitics

Diu had been a key strategic base for Portugal’s Indian Ocean empire, captured from the Ottoman Turks in a decisive sea battle in 1509 by Francisco de Almeida, who had convinced the local Muslim governor to change sides and thus not come to the aid of his religious compatriots. It was this victory that further cemented Portugal’s claim to control navigation in these waters. The poet Camões celebrates such conquest and treachery in

The Lusíads:

That Portuguese, they prophesy,

Raiding along the Cambay coast, will

Be to the Gujaratis such a specter

As haunted the Greeks in mighty Hector.…

The King of Cambay, for all his pride,

Will surrender rich Diu’s citadel,

In return for protecting his kingdom

From the all-conquering Mughal…

16

The sea gently knocked at the ramparts of the Portuguese citadel, the colors of mustard and lead from centuries of wear. The citadel is a triumph of fortress architecture—with a long landing pier, double gateway, rock-cut moat, and double line of seven bastions, each named after a Christian saint. Weeds crept through the stone, wild pigs wandered about, and packs of young male Indians, impervious to the historical explanations in Hindi

and Gujarati, loudly ambled along the stone works, seemingly unknowing of the significance of this immense curiosity, topped at its highest point by a lonely white cross. No guidebooks in any language were on sale, nor was there any entry fee or even a gatekeeper. The massive Portuguese churches here, with their colossal white Gothic facades, stood equally forlorn, their walls faded and leprous. You could actually see and hear the plaster falling at the close wing beats of pigeons. Inside these churches, after you had made your way past the tangle of garbage and overgrown white roses and oleanders, were cool, dark aromatic interiors conducive to prayer for the delivery of loved ones from the ravages of the sea. A few hundred years old, these dilapidated monuments are more like relics from antiquity, so divorced do they seem from the local environment.

Empires arise and fall. Only their ideas can remain, adapted to the needs of the people they once ruled. The Portuguese brought few ideas save for their Catholic religion, which sank little root among Hindus and Muslims, so these ruins are merely sad, and, after a manner, beautiful. By contrast, the British brought tangible development, ports and railways, that created the basis for a modern state. More importantly, they brought the framework for parliamentary democracy that Indians, who already possessed indigenous traditions of heterodoxy and pluralism, were able to fit successfully to their own needs.

17

Indeed, the very Hindu pantheon, with its many gods rather than one, works toward the realization of competing truths that enable freedom. Thus, the British, their flaws notwithstanding, advanced an ideal of Indian greatness. And that greatness, as enlightened Indians will tell you, is impossible to complete without a moral component.

As the influence of an economically burgeoning India now seeps both westward and eastward, it can do so only as a force of communal coexistence made possible by being, as the cliché goes, the world’s largest democracy. In other words, India, despite its flashy economic growth, is nothing but another gravely troubled developing nation without a minimum of domestic harmony. Mercifully, the forces of Indian democracy have already survived more than sixty years of turmoil, attested to by the stability of coalition governments following the era of Congress Party rule. These forces appear sufficiently grounded to either reject a Modi at the national level or to neuter his worst impulses as he moves at some point from Gandhinagar to New Delhi. After all, the churches and bastions in Diu are ruins not because they represent an idea that failed, but

because they represent no idea at all; whereas India has been an idea since Gandhi’s Salt March in 1930. Modi’s managerial genius will either be fitted to the service of that idea or he will stay where he is. Hindus elsewhere in India are less communal-minded than those in Gujarat, and that will be his dilemma. The coming together of Hindus and Muslims following the seaborne terrorist attack on a hotel and other sites in Mumbai in November 2008, originating from Pakistan, should have been a warning to him.

And if he did not get the message then, he certainly got it in May 2009 when Indian national elections gave the Congress-led coalition a decisive victory over Modi’s BJP. Indeed, the decline of Modi, which those elections might suggest, is as sure a sign as any of India’s triumphal entry into the twenty-first century. At the end of the day, despite all of the trends I have noted, I believe that enough Hindus will not ultimately give in to hate, regardless of the Muslim threat. We can thank India’s democratic spirit for that, a spirit that is truly breathtaking in terms of what it can overcome. That is India’s ultimate strength.

But in Gujarat, at least, peace will not come easily. From Diu I hired a car and drove two hours westward along the coast to Somnath, site of the Hindu temple destroyed by Mahmud of Ghazna, as well as by other invaders, and rebuilt for the seventh time starting in 1947.

Adorned with a massive pale ocher

shikhara

(tower) and assemblage of domes, this temple is located at the edge of a vast seascape glazed over with heat. Its coiled and writhing cosmic scenes on the facade are so complex they create the sculptural equivalent of infinity. Prayer blasted from loudspeakers. It was a madhouse on account of the full moon. Hundreds of worshippers checked their bags at a ratty cloak stand and left their shoes in scattered piles. Beggars attached themselves to me; hawkers were everywhere, as at many pilgrimage sites. Signs proclaimed that no mobile phones or other electronic devices would be permitted inside. I knew better, I told myself. I put my BlackBerry in my cargo pocket, not trusting it to the mild chaos of the cloak stand, and expecting the usual, lackadaisical third world frisk. I then joined the long, single file line to enter the temple. At the entrance, I was savagely searched and my Black-Berry discovered. I was rightly yelled at, and beckoned back to the cloak stand. “Muslim terrorism,” one worshipper alerted me. From the cloakroom I got back in line and entered the temple.

Semi-darkness enveloped me as worshippers kissed the flower-bedecked idol of a cow. The air was suffocating with packed-together bodies approaching the womb-chamber. I felt as if I were trespassing on a mystery. Though nonbelievers were officially welcomed, I knew that I was outside the boundaries of the single organism of the crowd—philosopher Elias Canetti’s word for a large group of people who abandoned their individuality in favor of an intoxicating collective symbol.

18

This sanctum was a pulsating vortex of faith. Some dropped to their hands and knees, and prayed on the stone floor. There was no seduction of outsiders as at the Vatican, a place diluted by global tourism; nor was this the Kali temple in Kolkata, where foreigners are regularly welcomed and accosted by “guides” demanding their money. The universalism of the kind I had experienced at the Sultan Qabus Grand Mosque in Oman, which celebrated material civilization throughout the Indian Ocean, was not missing here, it was simply irrelevant. I had had the same extreme and cloistered sensation inside the shrine of the Black Madonna at Cz stochowa in Poland, and in the Imam Ali Mosque in Najaf in Iraq, two of the holiest sites of Catholicism and Shiism, respectively; at the latter unbelievers are expressly forbidden and I had to sneak in with a busload of visiting Turkish businessmen.

stochowa in Poland, and in the Imam Ali Mosque in Najaf in Iraq, two of the holiest sites of Catholicism and Shiism, respectively; at the latter unbelievers are expressly forbidden and I had to sneak in with a busload of visiting Turkish businessmen.

Being here you could not help understanding Hindu feelings about Muslim depredations of this temple, one of India’s twelve Jyotirlingas (places with signs of light that symbolize the God Shiva). Emotions crackled like electricity, yet I thought of what human rights official Hanif Lakdawala had asked me in a pleading tone: “What can we poor Muslims of today do about Mahmud of Ghazna?”

THE VIEW FROM DELHI

O

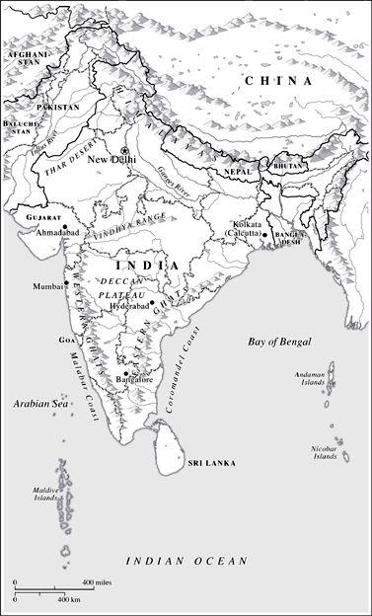

f all the periods of Indian Ocean history with which Gujarat is associated, and which are pertinent to our larger strategic discussion, among the most important is that of the Mughal Empire. Mughal emperor Akbar the Great marched into Ahmedabad in 1572 and completed the conquest of the province two years later. For the first time, the Mughals were rulers of a full-fledged coastal state with a substantial foothold on the Arabian Sea. Gujarat offered the Mughals not only possession of the busiest seaports of the Subcontinent at the time, but also a maritime kingdom that included vast and rich agricultural lands, and was in addition a powerhouse of textile production. By linking Gujarat with the Indo-Gangetic plain, and with soon-to-be-conquered Bengal, Akbar secured a subcontinental empire that spanned the two great bays of the Indian Ocean: the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal. It was by conquering Gujarat that Akbar saved India from disintegration, and from falling further into the hands of the Portuguese, whose hold on Goa threatened the other Arabian Sea ports.

Few empires have boasted the artistic, religious, and cultural eclecticism of the Mughals. They ruled India and parts of Central Asia from the early 1500s to 1720 (after which the empire declined rapidly). Like the Indian Ocean world of which it was a part, the Mughal Empire was a stunning case in point of early globalization. Take the Taj Mahal, the white marble mausoleum built on the bank of the Yamuna River in Agra by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan to honor his wife Mumtaz Mahal, who died in childbirth (her fourteenth) on June 17, 1631. The tomb fuses all the liberating grace and symmetry of the best of Persian and Turkic-Mongol architecture, with an added Indian lightness and flair. It is as though, with its globular dome and four slender minarets, it is able to defy gravity and float off the ground itself. There is a romance to the tomb and the story surrounding it that makes one forget that Shah Jahan was an extremely orthodox Muslim whose rule, according to Duke University history professor John F. Richards, represented a “hardening” of relations between the dominant Muslims and those of other faiths in the Subcontinent.

1

Mughal is the Arabic and Persian form of Mongol, which was applied to all foreign Muslims from the north and northwest of India. The Mughal Empire was founded by Zahir-ud-din-Muhammad Babur, a Chaghatai Turk born in 1483 in the Fergana valley in today’s Uzbekistan, who spent his early adulthood trying to capture Tamerlane’s (Timur’s) old capital of Samarkand. After being defeated decisively by Muhammad Shaybani Khan, a descendant of Genghis Khan, Babur and his followers headed south and captured Kabul. From there Babur swept down with his army from the high plateau of Afghanistan into the Punjab. Thus, he was able to begin his conquest of the Indian Subcontinent. The Mughal, or Timurid, Empire that took form under Akbar the Great, Babur’s grandson, had a nobility composed of Rajputs, Afghans, Arabs, Persians, Uzbeks, and Chaghatai Turks, as well as of Indian Sunnis, Shias, and Hindus, not to mention other groups. In religion, too, Akbar’s reign of forty-nine years (1556–1605) demonstrated a similar universalism. Akbar, who was illiterate, possibly the result of dyslexia, spent his adult life in the study of comparative religious thought. And as his respect grew for Hinduism and Christianity, he became less enamored with his own, orthodox Sunni Islam. In his later years, writes Richards in his rich yet economical history of the Mughal Empire, Akbar gravitated toward a “self-conceived eclectic form of worship focused on light and the sun.”

2

Moreover, he championed an “extraordinarily accommodative, even syncretic style of politics,” even as he governed in the courtly style of a traditional Indian maharaja, as demonstrated in the miniature paintings.

3

All that changed under his successors Jehangir, Shah Jahan, and especially Aurangzeb, who returned the empire to a fierce Sunni theocracy that, nevertheless, tolerated other sects and religions. This very religious dynamic was a factor in the tense relations between Mughal India and Safavid Persia. Although Persian administrators were among the largest

ethnic groups in the Mughal nobility, the Safavi Persians, who were fervent Shias, showed contempt for the Sunni Timurids governing India. This extreme dislike was intensified by the uncomfortable cultural similarity between the two empires that shared a common frontier through what is today western Afghanistan, for the Mughal imperium truly conjoined India and the Near East.