Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power (23 page)

Read Monsoon: The Indian Ocean and the Future of American Power Online

Authors: Robert D. Kaplan

Tags: #Geopolitics

India was the ultimate paradox. It dominated the Subcontinent much as the British had, yet unlike the viceroys it was bedeviled by land borders in which the only state within the Subcontinent that was not dysfunctional was India itself. All the others—Pakistan, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Burma—were supreme messes of countries. Pakistan and Bangladesh made no geographical sense. They were artificial constructs in places where the political map had changed dramatically over

the decades and centuries. Nepal and its dozen ethnic groups had been held together by a Hindu monarchy torn asunder by gruesome murders, and finally replaced by a fragile new democracy. Sri Lanka’s rival ethnic groups had been engaged in a generation-long war whose embers were still hot. And Burma’s very sprawling and rugged topography made it home to several ethnic insurgencies that had provided the raison d’être for military misrule. Only India, despite its languages, religions, and ethnicities, dominated the Subcontinent from the Himalayas to the Indian Ocean, providing it with geographical logic. Democracy helped immeasurably by giving all these groups a stake in the system. The Naxalite terrorists notwithstanding, India was inherently stable—in other words, it could not fall apart even if it wanted to.

Yet dealing with all of its problems on a daily basis, even as its naval chief contemplated sea power as far away as Mozambique and Indonesia, provided the inhabitants of these awesome government buildings with a sense of modesty that the British, with all of their realpolitik, lacked. Thus, the Indians might occupy this magnificent perch at the confluence of Central Asia and the Hindu plain longer and ultimately more fruitfully than did their predecessors. The real art of statesmanship was to think tragically in order to avoid tragedy.

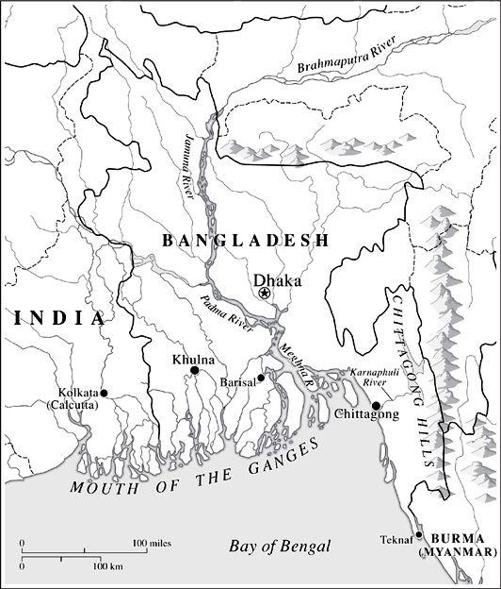

India stands dramatically at the commanding center of the Indian Ocean, near to where the United States and China are headed for a tryst with destiny. Just as America is evolving into a new kind of two-ocean navy—the Pacific and the Indian oceans, rather than the Pacific and the Atlantic—China, as we shall see in a later chapter, may also be evolving into a two-ocean navy—the Pacific and the Indian ocean, too. The Indian Ocean joined to the western Pacific would truly be at the strategic heart of the world. But before we complete this picture, it is necessary to take a close look at other countries along the Indian Ocean’s littoral, particularly those on the Bay of Bengal. Let’s start with India’s neighbor Bangladesh, which was also part of the Mughal Empire.

*

Until the Mughals’ invasion, Bengal itself had been under the less organized Delhi Sultanate from the end of the twelfth century.

*

India was expected to surpass China around 2032 as the world’s most populous country.

*

The navy’s share of the Indian defense budget had doubled from the early 1990s. Walter C. Ladwig III, “Delhi’s Pacific Ambition: Naval Power, ‘Look East,’ and India’s Emerging Influence in the Asia-Pacific.”

Asia Security

, vol. 5, no. 2 (May 2009).

*

Daniel Twining, “The New Great Game,”

Weekly Standard

, Dec. 25, 2006. Only in 2005 did India recognize Chinese sovereignty over Tibet; in return, China recognized Indian sovereignty over the Himalayan state of Sikkim.

†

Some Indians liked to point out that China opposed the selling of uranium to India by Australia, for use in India’s nuclear program, which suggested to them that China opposed the very emergence of Indian power.

*

Pakistan regularly accuses India of using its newly opened consulates in Afghanistan to support the Baluch separatist movement.

*

Facing, in its own view, a missile threat from China and Pakistan, India was also an ally of the United States on the issue of missile defense.

BANGLADESH

THE EXISTENTIAL CHALLENGE

T

he Indian Ocean alone among the world’s great bodies of water is, in the words of Alan Villiers, an “embayed” ocean. While the other oceans sweep from north to south, from Arctic to Antarctic ice, the Indian is blocked by the landmass of Asia, with the inverted triangle of peninsular India forming two great bays, the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal.

1

The Arabian Sea is oriented toward the Middle East; the Bay of Bengal toward Southeast Asia, with the Mughals having a perch on both. But it is the monsoon that truly unites them. It ignores national borders with its vast geographical breadth. Pakistanis in Karachi watch closely the progress of the boisterous southwest monsoon northward along India’s Malabar coast in the Arabian Sea; Bangladeshis do likewise as this monsoon churns its way up through the Andaman Sea off Burma, culminating at the top of the Bay of Bengal. My visits to the Bay of Bengal were almost always during the spring and summer monsoon rains, so these shores have retained a darker, though not unpleasant cast in my mind compared to the other seaboard farther west, that of the Arabian Sea.

The southwest monsoon that arrives in the Bay of Bengal in early summer provides a new dimension to rain. This is the time of tropical cyclones, and it is as though the ocean was continually emptying itself upon you. For days at a time, the sky is a low, claustrophobic vault of angry clouds. Absent sunlight, the landscape—however intrinsically rich in color, with mountains of hibiscus and bright orange mangoes, and the flowing saris of women—becomes scrubbed over in a grainy mist. Mud is the primary color, but it is not depressing. It is the coolness that you notice first, not the leaden darkness. You are filled with energy. No longer are your clothes dissolving in sweat or your knees hollow from the heat. No longer is the air something thick and oppressive that your body needs to push against.

The monsoon—from the Arabic

mausim

, meaning “season”—is one of the earth’s “greatest weather systems,” generated by the planet’s very rotation, and also by climate. As the landmass on the Indian Ocean’s northern shores near the Tropic of Cancer heats up in the summer, producing spectacularly high temperatures, a low-pressure zone forms near the surface, equalized by cooler air starting to flow in from the sea. When this cool, moist sea air meets the hot dry air of the Asian mainland, the cool moist air rises in upward currents, producing clouds and rain.

*

There is something truly mathematical about it, as the monsoon’s two branches reach Cape Comorin and Bangladesh around June 1, Goa and Kolkata five days after that, then Mumbai and Bihar five days after that, Delhi in mid-June, and Karachi around July 1. It is the monsoon’s dependability that inspires such awe, and on which agricultures and local economies consequently depend. A good monsoon means prosperity, so a shift in weather patterns due to possible climate change could spell disaster for the littoral countries. There is already statistical evidence that global warming has caused a more erratic monsoon pattern.

2

The southwest monsoon in Bangladesh arrived while I was in a shallow draft boat traveling over a village that was now underwater. In its place was a mile-wide channel, created by erosion over the years, which separated the mainland from a

char—

a temporary delta island formed by silt, that would someday just as easily dissolve. As ink-dark, vertical cloud formations slid in from the Bay of Bengal, the small boat made of rotting wood began slapping hard against the waves. Following days of dense soupy heat, rain fell like nails upon us. The boatman, my translator, and I made it to the

char

before the channel water that was splashing into the

hull, heavy with silt, threatened the boat’s buoyancy. We started bailing. It was a lot of work just to see something that was not there anymore.

Some days later, in order to see a series of dam collapses that had been progressing inland, and which had led to the evacuation of more than a dozen villages, I rode on the back of a motorcycle along an interminable maze of embankments that framed a checkerwork of paddy fields glinting mirror-like in the steamy rain. Once again, the sight at the end of my journey—a few crumbled earth dams—was not dramatic, unless you had a “before” picture with which to compare it.

Climate change and attendant sea-level rises provide few straightforward visuals. Pictures of Arctic ice melt are dramatic only because the Arctic is itself dramatic. As sudden as the changes may be in geological time, to us they still occur in slow motion. Rivers will shift course overnight, and dams will collapse instantly, following a slight but pivotal rise in hydraulic pressure. But in such cases you have to be there when it happens.

Yet, from one end of Bangladesh to the other, in the early weeks of the monsoon, I saw plenty of drama, registered in this singular fact: remoteness and fragility of terrain never once corresponded with a paucity of humanity. Even on the

chars

, I could not get away from people cultivating every inch of alluvial soil. Human beings were everywhere on this dirty wet sponge of a landscape traversed by narrow, potholed roads and grimy, overcrowded ferries, where the beggars and peddlers appeared to sleepwalk between the cars in the pouring rain.

I went through towns that had a formal reality as names on a map, but were little more than rashes of rusted, corrugated iron and bamboo stalls under canopies of jackfruit, mango, and lychee trees. These towns teemed with men wearing traditional skirtlike

longyis

and baseball hats, and women who over the years were increasingly garbed in Muslim burkas that concealed all but their eyes and noses. Between the towns were long lines of water-filled pits, topped with a green scum of algae and hyacinths, where the soil had been removed in order to raise the road a few feet above the unrelenting, sea-level flatness.

Soil is so precious in Bangladesh that riverbeds are dredged in the dry season to find more of it. It is a commodity that is always on the move. When houses are dismantled, the ground on which they stand is transported through wet “slurry pipes” to the new location. “This is a very transient landscape, what’s water one year can be land the next, and vice

versa,” explained an official of the U.S. Agency for International Development in Dhaka, the capital. “A man can dig a pit, sell the soil, then raise fish in the new pond.”

In every respect, people were squeezing the last bit of use out of the earth. One day I saw a man carried on a stretcher moments after he had been mauled in the face and ear by a royal Bengal tiger. It is not an uncommon occurrence, as fishing communities crowd in ever closer on to the tigers’ last refuge in the mangrove swamps of the Bangladeshi-Indian border area, even as salinity from rising sea levels has led to a sharp reduction in the deer population on which the tigers feed. Neither man nor tiger has anywhere else to go.

The earth has always been unstable. Throughout geological history flooding and erosion, cyclones and tsunamis have been the norm rather than the exception. But never before have the planet’s most environmentally frail areas been so crowded. Although the rate at which world population grows continues to drop, the already large base of population guarantees that absolute rises in the number of human beings have never been greater in countries that are most at risk. This means that over the coming decades more people than ever before, in any comparable space of time save for a few periods like the fourteenth century during the Black Death, are likely to be killed or made homeless by Mother Nature. The Indian Ocean tsunami of December 2004 was a curtain raiser for disasters ahead.

People joke sometimes about how thousands of people displaced by floods in Bangladesh equals, in news terms, a handful of people killed or displaced closer to home. But that comparison, in addition to its cruelty, is blind to where natural events may be headed. The U.S. Navy may be destined for a grand power balancing game with China in the Indian and Pacific oceans, but it is more likely to be deployed on account of an environmental emergency, which is what makes Bangladesh and its problems so urgent.

With 150 million people living packed together at sea level, the lives of many millions in Bangladesh are affected by the slightest climatic variation, let alone by the dramatic threat of global warming. The possibility of an eight-inch rise in sea level in the Bay of Bengal by 2030 would devastate more than ten million people, notes Atiq Rahman, executive director of the Bangladesh Centre for Advanced Studies. The

partial melting of Greenland ice alone over the course of the twenty-first century could inundate more than half of Bangladesh in salt water. Although such statistics and scenarios are hotly debated by scholars, one thing is certain: Bangladesh is the most likely spot on the planet for the greatest humanitarian catastrophe in history. And as I saw, it would affect almost exclusively the poorest of the poor.