Moonshot: The Inside Story of Mankind's Greatest Adventure (29 page)

Read Moonshot: The Inside Story of Mankind's Greatest Adventure Online

Authors: Dan Parry

Tags: #Technology & Engineering, #Science, #General, #United States, #Astrophysics & Space Science, #Astronomy, #Aeronautics & Astronautics, #History

BOOK: Moonshot: The Inside Story of Mankind's Greatest Adventure

13.57Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

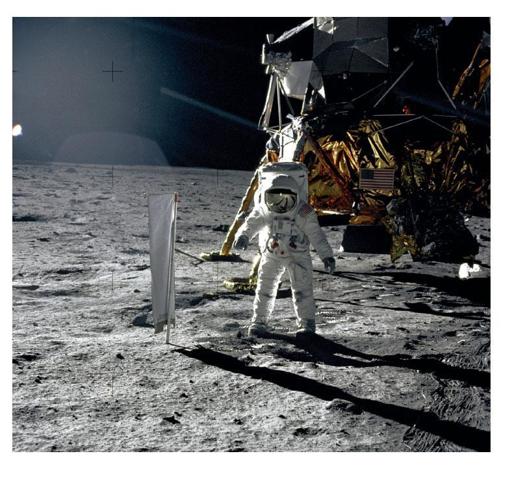

Aldrin beside the US flag. The footprints of the astronauts are clearly visible in the soil of the Moon.

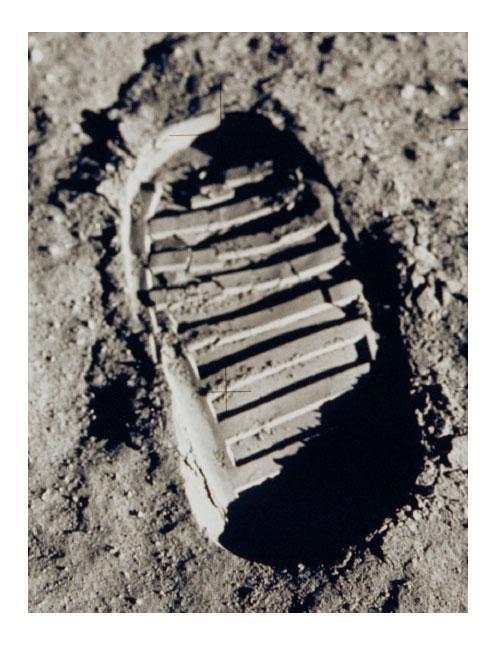

One small step ... Buzz Aldrin's bootprint.

Buzz Aldrin and, to his right, the Solar Wind Composition experiment.

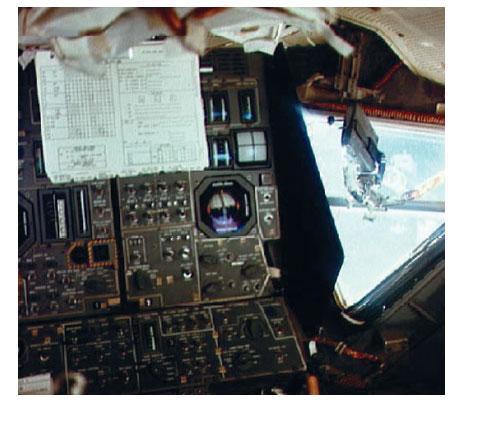

A relieved Armstrong back in the LM after the moonwalk.

Buzz's position on the right-hand side of the lunar module cabin. In the window is a 16mm film camera.

Lt. Clancy Hatleberg closes the spacecraft hatch while the crew await rescue. Leaving Columbia Aldrin said he was struck by a 'peculiar sense of loss'.

Officials join the flight controllers in celebrating the return of Apollo 11. Third from left (foreground) is Chris Kraft, fourth is George Low and fifth is Bob Gilruth.

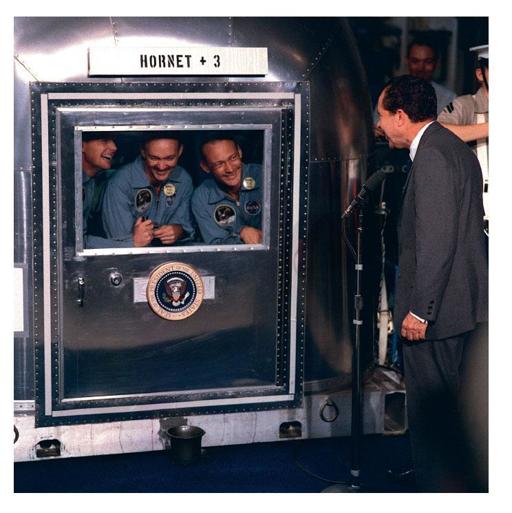

President Nixon welcomes the astronauts aboard the USS Hornet. The crew are already confined to the Mobile Quarantine Facility, MQF).

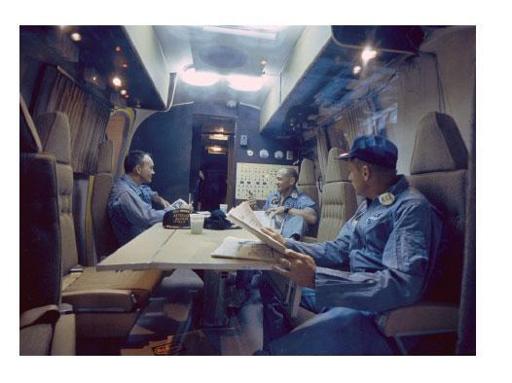

Inside the quarantine facility.

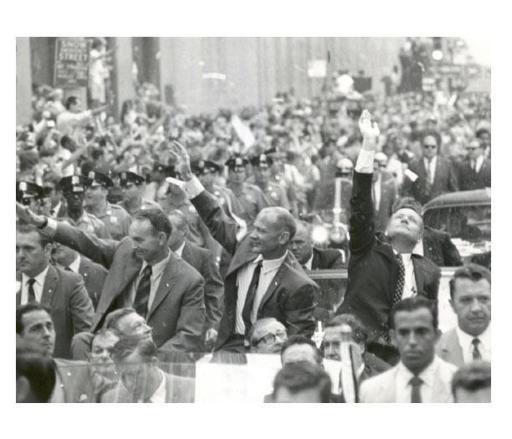

New York City welcomes the three astronauts, in a shower of ticker tape.

Chapter 11

A PLACE IN HISTORY

On 10 July 1969, Frank Borman returned from an official goodwill trip to Russia. Three days later he was still briefing senior politicians in Washington when Chris Kraft urged him to find out what he could about the Luna 15 mission. Borman consulted the National Security Advisor, Henry Kissinger, before using the infamous White House hotline to call the Soviet Academy of Sciences. The following day, telegrams detailing the probe's trajectory and promising that radio interference would not be a problem were sent to the White House and to Borman's home in Houston.

1

In a rare moment of co-operation, the two superpowers were brought a hair's width closer through a spirit of unity fostered by the leaders of their respective space programmes. In space at least, if not elsewhere, the Cold War was showing signs of a thaw.

An atmosphere of mutual respect between astronauts and cosmonauts developed in rare meetings at international air shows. In May 1967, Michael Collins was asked by NASA to attend the Paris Air Show, along with Dave Scott. Besieged by photographers, autograph hunters, security men and tourists, they sat down with cosmonauts Pavel Belyaev and Konstantin Feoktistov. But the formalities evaporated when everyone retreated to the privacy of the Russians' airliner and opened the vodka. The Russians insisted they had no plans for a manned landing on the Moon but admitted that cosmonauts were training to fly helicopters, leading Collins to suspect that secretly their lunar ambitions were far from over.

Compared to NASA's open way of doing things, Collins considered the Russian space programme to be 'hidden from view, secret and mysterious'.

2

This was a widely held opinion. The Russians never announced flights in advance and disasters were always concealed. News of the loss of cosmonaut Valentin Bondarenko, during a training accident in 1961, did not emerge until the 1980s.

3

Worse, many in NASA believed the Russian space programme to be tinged with a nasty communist way of doing things, including ordering cosmonauts to undertake risky ventures simply to beat the Americans in achieving key objectives. The Russians might have put the first man in space, and the first woman, and carried out the first EVA, but some in NASA wondered just how much risk they were accepting along the way. There were indeed occasions when cosmonauts were sent on missions against their better judgement. Unknown to NASA, Vladimir Komarov had raised concerns about the many technical problems with Soyuz 1, before it claimed his life in April 1967.

4

Yet the fact that the Russians were sometimes getting ahead of themselves, and consequently taking unnecessary risks, did not prove that NASA occupied the moral high ground. It was the Americans who had publicly set a deadline, forcing developments to move forward so quickly that while the Russians lost one man during a mission NASA lost three on the ground. A month after Komarov died, Collins, Scott, Belyaev and Feoktistov drank to an end to accidents.

By 1968, the CIA was warning NASA's leadership of a giant rocket being secretly built by the Russians.

5

It appeared that Moscow was preparing to send men to the Moon, in an attempt to beat the Americans once again and steal the ultimate prize laid down by Kennedy. In fact Kennedy, as we have seen, had invited Khrushchev to take part in a joint expedition to the lunar surface. Although the Russians were receptive to the president's UN speech, they were never to find out what he had in mind.

6

After Kennedy's assassination Khrushchev was persuaded to go it alone, and he secretly set in motion the necessary preparations – as Collins had suspected. A top priority was a powerful rocket to rival the Saturn V, and by February 1969 the Russians were ready to test their N-1 booster. Although big enough to impress the CIA, the N-1 lacked the Saturn's reliability and exploded just over a minute into its flight. On 3 July, just two weeks before the launch of Apollo 11, a second N-1 blew up, the huge explosion destroying its launch-pad at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan and bringing an end to any realistic hope of a Russian manned mission to the Moon. No announcement was made of the disaster and the world did not learn of it for some months to come.

7

Other books

Impulse by Vanessa Garden

Out of Control by Shannon McKenna

Sold To The Bears (A BBW Paranormal Romance Book 1) by Amira Rain, Simply Shifters

Lady Thief: A Scarlet Novel by Gaughen, A.C.

You Don't Love This Man by Dan Deweese

Sinema: The Northumberland Massacre by Rod Glenn

Laina Turner - Presley Thurman 07 - Cupids & Crooks by Laina Turner

The Exile by Mark Oldfield

Wicca by Scott Cunningham

Sugar and Spice by Sheryl Berk