Niagara: A History of the Falls (49 page)

Read Niagara: A History of the Falls Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Meanwhile, Moses had renewed his offer of $1.5 million for the 1,383 acres of Tuscarora land. He had already agreed to pay the neighbouring Niagara University $5 million for two hundred acres. In addition, he had sweetened the offer to the Indians, not only with the community centre but also with promises of new roads and free electricity. He even promised to name one of the big generators Tuscarora. The Indians laughed at this. For the first time, Moses began to talk about building a much smaller reservoir outside the reservation.

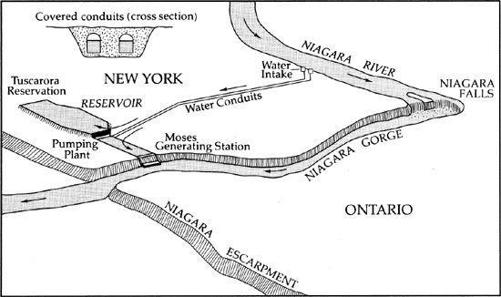

Moses continued to press forward in his usual way with construction of the generating plant. As always he was right on schedule. Thirty-five hundred men were now working on the plant and on the huge conduit ditch, one hundred feet deep and four hundred feet wide, being gouged from the rock of the Niagara Escarpment. Eight temporary bridges were being constructed, and five million yards of earth and rock had already been removed. Before the job was complete, the bridges would be torn down and the great cut covered over. The estimated cost had now soared to $720 million.

The covered conduits to the Moses powerplant

In January 1959, the FPC delayed its findings, hoping for an out-of-court settlement. A desperate Moses was now offering $2.5 million for the Indian land. At a tribal meeting, Lazarus, the Tuscarora’s lawyer, urged them to negotiate in good faith. Clinton Rickard’s son, William, opposed him, pointing out that the public would think the Tuscarora were simply holding out for more money when they had already said they wouldn’t sell for any price. The atmosphere was heated even though the room temperature stood at twelve degrees below zero. In spite of the cold, the debate continued until two in the morning.

Rickard was convinced that Moses was out to create a disunity among his people. Cries of “Sell out! Sell out!” were heard from a minority. The majority agreed to continue negotiations, causing the press to speculate that the Tuscarora

did

have a price. That suspicion was reinforced when Moses upped the ante again to $3 million – more than twice what he had originally suggested he might pay. He set March 1 as a final deadline when the agreement would have to be signed.

The Rickards, father and son, were in despair, for the Indians appeared to be divided as a result of the new offer. “Money is like water in your hands,” they had often said. “It falls through your fingers and disappears. But the land lasts forever.” Would the Tuscarora heed this message?

The Tuscarora were to vote on Moses’ offer on the evening of January 29, 1959. That morning, William Rickard received a letter from a friend describing the struggle for civil rights among the blacks in the South. At the meeting he read the letter aloud. Surely, he said, the Tuscarora could be just as courageous. In forty-five minutes the Indians voted unanimously to reject the money.

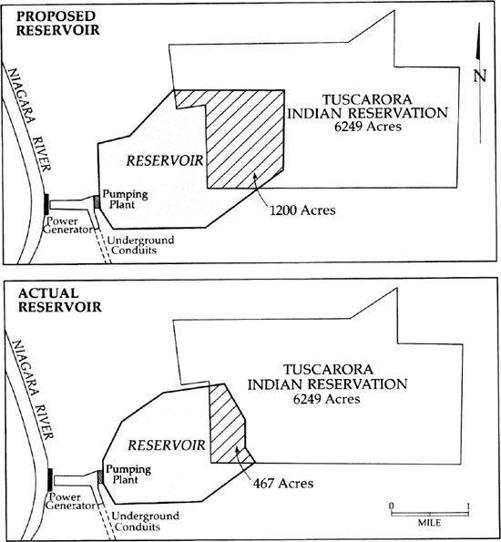

Just four days later the FPC handed down its decision, ruling that the use of the Indian land for a reservoir was inconsistent with the purpose for which Indian reservations had been established. The contractors removed their equipment, and Moses announced ruefully that he would build the reservoir on private land expropriated outside the disputed area. By increasing the height of the dikes by ten feet he could cut in half the contemplated loss in capacity.

It was generally accepted that the Indians had won and that Moses was beaten. But Moses was not a man who ever gave in. Apparently, the March 1 deadline was not inviolate, for he now filed a request for a new hearing before the FPC – one that would certainly drag out far beyond that date. Moses had scaled down his demands, announcing that he would now need no more than 470 acres of the reservation for power lines, a road, and part of the reservoir, most of which would occupy land outside the Indian boundaries. Moses had earlier refused to consider this solution.

More delays. The federal government stepped into the dispute, contending that the law, as the FPC interpreted it, applied only to land held by the government in trust for the Indians. The Tuscarora

owned

their reservation; the government had no power over it. Once again the case moved to the Supreme Court.

The court did not review the case until December and did not publish its decision until March 7, 1960 – and it was a shocker. The court pointed out that the tribe had not acquired their land by treaty but by gift and purchase. By a vote of six to three, the court held that inasmuch as the lands were owned in fee simple by the Tuscarora nation and that no interest in them was owned by the United States, “they are not within a ‘reservation’ as that term is defined and used in the Federal Power Act.…”

The three liberal judges on the bench, Chief Justice Earl Warren, William O. Douglas, and Hugo Black, dissented. “Some things are worth more than money and the costs of a new enterprise,” Black wrote. “I regret that this court is to be the governmental agency that breaks faith with this dependent people. Great nations, like great men, should keep their word.”

The battle was over. The Indians had lost and Moses was triumphant. “A Niagara of fictional treacle and molasses has been poured on the Indians, a sticky flow finally stopped by the United States Supreme Court,” he declared triumphantly in a speech before the New York State Society of Newspaper Editors that June.

But Moses hadn’t really won. He did not get his 1,383 acres; he got only 467, which included the land taken earlier for the power line. Most of the reservoir would be outside the reservation after all. Nor was the new plan as devastating to the project as Moses had suggested. The reduction in power would be minor – 1,700,000 kilowatts instead of 1,800,000.

The Tuscarora continued to brood over the court decision. “Many of our white friends have assured us that even though we lost the land, we gained a moral victory,” Chief Rickard wrote after the fact. “We unfortunately live in a day when moral victories count for little.” The families who occupied the land taken for the reservoir were moved. Those who lost land were paid for it. The remainder of the Tuscarora received eight hundred dollars apiece.

The scaled-back reservoir on the Tuscarora’s land

“The SPA got its reservoir and we were left with scars that will never heal,” Rickard said. Some years later he described the permanent damage that had been done by the reservoir. “It has ruined the fishing on our reserve by damming up the inlet. The Northern Pike like to lay their eggs in swampy areas and our reservation provided several such places for them. Now they are gone, along with the other fish that liked to swim in our waters. We have never been compensated by the state for this loss.…”

At 11:30 on the morning of Friday, February 10, 1961, the governor of New York, Nelson Rockefeller, pulled a symbolic red-handled switch and formally put into service the largest water-driven power complex in the world. The president, John F. Kennedy, and three of his predecessors sent recorded greetings. The specially commissioned mural by Thomas Hart Benton, showing Father Hennepin at the Falls, was unveiled. Ferde Grofé conducted the premier performance of his

Niagara Suite

, which Moses had commissioned, hoping (vainly) that it would be as popular as Grofé’s earlier

Grand Canyon Suite

.

Moses himself was the recipient of unadulterated praise from press and politicians. He was, in Rockefeller’s words, “a giant of a man … a man of unique and almost incredible accomplishments … a man of fabulous energy and imagination and a genius for getting things done.…” Moses’ reply was brief. “After long, stultifying and maddening delays and obstructions, it has through persistence and, I suppose, luck, finally come about.”

But Robert Moses was not a man who believed in luck. It had been his own persistence that had got the job done exactly on schedule, just 1,107 days after the first bulldozer bit into the sod on the edge of the Niagara gorge. Moses had achieved it through a combination of bulldog tenacity, hard driving, devious politicking, and sheer charm. The powerplant itself was accomplishment enough, but it was the tremendous face-lifting over which Moses had presided that was his true monument. Moses had never seen the powerplant as an end in itself, but simply a means to restore the American side of the gorge by providing the parklike atmosphere needed to enhance the glory of the Falls. This was his larger vision, and he lived to see it completed.

Moses’ name was enshrined on both the Robert Moses Parkway and the Robert Moses Niagara Power Plant, but his term at the power authority was about to end. Nelson Rockefeller, with as strong a personality as the power commissioner’s, tried to ease him out gently; after all, Moses was long past retirement age. But Moses wouldn’t go gracefully. In a burst of anger, he quit all his state posts and issued a furious press release attacking the governor.

That was not quite the end of Robert Moses. In assuming the presidency of the private corporation that was to build and operate the 1964-65 World’s Fair in New York, he again put his reputation on the line, only to tarnish it irrevocably. It was not the big fair that interested him. It was his grandiose scheme to use its profits to pay for the greatest city park in the world on its site at Flushing Meadows. The scheme failed, and Moses had to take the blame for his bullheadedness, which antagonized everybody from the European nations that unanimously boycotted the exposition to the press itself. The fair lost $11 million. Moses, by defaulting on the fair’s debt to the city, managed to scrape together enough funds to clean up the site. What remained was a far cry from the park of his dreams – a vast 1,346 acres of green space on the rim of the expanding metropolis. But in the view of Moses, the park man, it was still a park of sorts, and for him that was all that counted.

Chapter Twelve

1

The miracle

2

Blackout

3

Drying up the Falls

1

The miracle

The construction of the Moses powerplant turned Niagara Falls, New York, into a city of trailer camps. A total of eleven thousand men worked on the plant, on the reservoir, and on the conduits leading to it. Many, like Frank E. Woodward, a carpenter, had long been accustomed to a gypsy-like existence, moving from city to city, whenever and wherever the work beckoned. Frank’s younger child, Roger, was only seven when the family moved to the area in the winter of 1959-60. He’d already been in two schools in two different communities. The 95th Street School would be his third.

The Woodwards and their two children, Roger and Deanne, aged seventeen, lived in the Sunny Acres Mobile Home Park, not far from the job. Frank’s foreman, James Honeycutt, lived in Lynch’s Trailer Park in the neighbouring community of Wheatfield. Both men worked for Balf, Sarin and Winkelman, building the big conduits.

On Saturday afternoon, July 9, 1960 – a day that the Woodwards would always remember and that would eventually change the direction of Roger Woodward’s life – Jim Honeycutt dropped over to Sunny Acres and offered to take the Woodwards for a boat ride. Frank Woodward and his wife declined, but Deanne and Roger eagerly accepted. “Remember to wear your life jacket,” Frank called out to Roger, who was just learning to swim.

Honeycutt, an experienced boatman and a strong swimmer with six years’ experience as a lifeguard in North Carolina, had done considerable boating on the upper Niagara south of Grand Island. He owned a twelve-foot aluminum craft, powered by a seven-and-a-half-horsepower Evinrude outboard. The trio set off from Grand Island to explore the river. It was a blistering hot day, and Roger wanted to remove his life jacket. But Honeycutt, remembering Frank Woodward’s warning, insisted that he keep it on. In later years, Roger Woodward, looking back on the scene, could never understand Jim Honeycutt’s purpose in taking the boat under the Grand Island bridge and into the strange and turbulent waters below. Was it accidental, or did he intend to give the children the thrill of their lives?