Niagara: A History of the Falls (46 page)

Read Niagara: A History of the Falls Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

His ability to stifle opposition was legendary. “There is little profit in arguing with Bob Moses,” the editor of a Syracuse newspaper wrote in 1959. “He is living proof of what a large vocabulary featuring words and terms of scorn, derision, and colossal contempt, can do for a public official when directed at an opponent with machine-gun rapidity. If and when I become embroiled in a controversy with Moses, I will insist in advance on a verbal handicap. There is no percentage in taking him on from a standing start.”

Moses himself never shrank from a fight; indeed, he welcomed controversy. “I recommend to my boys that they grow a tough hide rather than cover a thin skin with protective colouring, suntan oil, perfume and deodorants,” he once remarked. His mail, he complained, “often takes its tone from whiners and brick throwers.” But, he said, he was determined never to be deterred from his purposes. “The armour-plated rhino and the crocodile should be our symbols and our answer to the pea shooters should always be: ‘You never touched me.’ ”

Governor Thomas E. Dewey made Moses an energy czar because of his reputation as a doer. More than any other man, Moses had shaped New York City and much of New York State. He had built sixteen expressways and seven great bridges, including the famous Triborough. He had installed 685 playgrounds. He had torn down acres of slums to put up public housing. His thru way’s had displaced a quarter of a million people. Peter Cooper Village and Stuyvesant Towers, those monuments to “urban renewal” (the buzz-word of the fifties), were his doing. So were Shea Stadium, the New York Coliseum, the United Nations headquarters, and Lincoln Center.

He had made himself the most powerful man in the biggest city on the continent – more powerful at times than the mayor himself. He was admired, feared, and hated in roughly equal measure. Now, in addition to the several hats he already wore, he had donned a new one. He would be responsible not only for the Niagara project but also for the United States’ commitment to the St. Lawrence Seaway.

In the late forties, with the international agreement dividing Niagara’s water between the two nations about to expire, and with power blackouts irritating consumers on both sides of the border, Ontario Hydro pressed for a new document. Signed at the end of February, 1950, it changed the previous water allotment, in which Canada had been allowed to draw 56,500 cubic feet a second from the Falls and the United States 32,500. The new diversion treaty simply declared that

all

the water in the river could be used to develop power – after the scenic protection of the Falls was guaranteed.

That meant that not less than 100,000 cubic feet a second must be allowed to flow over the Falls in the summer months. The flow would be reduced to 50,000 between November 1 and April 1, when few tourists paid the Falls a visit. What was left could be divided equally between the two countries.

Four days after the treaty became law, Ontario Hydro had its project under way. Hydro’s dynamic new chairman, Robert Saunders, announced that a second generating plant, also to be named for Sir Adam Beck, would soon be built a few yards upstream from the first. It would be designed to produce 700,000 horsepower at a cost of $157 million. That same summer, John E. Burton, then chairman of the New York State Power Authority, offered to build and pay for a similar massive generating plant directly across the river from the Hydro structures.

Saunders wasted no time. Construction on the Ontario plant began in December 1950. But when Moses replaced Burton four years later, American politicians were still wrangling over whether a private or a public company should do the job at Lewiston. The contrast between the two systems – American and Canadian – was never better demonstrated than by the spectacle of the Lewiston site standing idle while its Canadian counterpart was alive with activity. The American concept of grass-roots democracy demanded that every elected politician should have his say before a single foot of turf was disturbed. The Canadian method of dispensing authority from above – a remnant of the British colonial system – was more efficient, if less democratic.

As chairman of the provincially owned corporation, the forty-four-year-old Saunders needed nothing more than the Ontario government’s permission to go ahead. With the province facing more power blackouts, it would have been political suicide not to build Beck 2. Saunders, after all, had been the government’s choice to head Hydro, which was also deeply involved in the new St. Lawrence Seaway project.

Niagara Falls power seemed to attract powerful men. Like Adam Beck before him, and like Robert Moses, his opposite number in the United States, Robert Saunders was a strong personality. A fireman’s son, he had risen successively from farm worker, to truck driver and factory hand, to one of Toronto’s most successful and best-loved mayors. A brilliant administrator and a master publicist, he seemed the right man to allay the growing public irritation over the continuing power shortage. Stumping the province in a marathon series of speeches, delivered in a gravelly voice, he levelled with his audience and managed to break through the massive crust of secrecy that had heretofore concealed Hydro’s inner workings.

That was why he was chosen. A glad-hander and a collector of celebrities who always managed to manoeuvre himself into the centre of any news photograph, Saunders also knew how to manipulate the press. He remembered the name of everybody he met and with his photographic memory quickly absorbed the minutiae of Hydro development. Soon he was able to astonish colleagues and newsmen alike by reeling off figures on how much power this or that Hydro plant had generated on any given day, or how many farms were served by rural power lines, and even the number of people living on those farms.

The ex-mayor’s hail-fellow personality endeared him to Hydro workers. On seeing a work crew, he would leap from his chauffeured limousine, greet them with a “Hi! I’m Bob Saunders,” and ask about the job. Later he would send along cards or letters of congratulation. Every Sunday on Canada’s largest radio station, CFRB in Toronto, he’d report to the public and welcome questions. “Good afternoon, ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, this is your Hydro chairman reporting,” he’d announce. He didn’t think it necessary to identify himself by name, secure in the knowledge that every listener knew who he was.

He loved the sound of his own voice and would sometimes argue heatedly with his chauffeur, “Swifty,” on events of the day. Once, en route to Niagara, the argument grew so heated that Saunders ordered Swifty to stop the car. He eased the chauffeur out of his seat, took the wheel himself, and drove off, leaving Swifty alone on the highway to find his own way to the Falls.

Like Beck before him, but unlike Beck’s successors, Saunders adopted a hands-on policy at Hydro. Earlier chairmen had confined their duties to acting as spokesmen for the commission. Saunders, however, wanted a say in internal decisions, which, though it caused some friction with upper management, helped speed the construction of Beck 2.

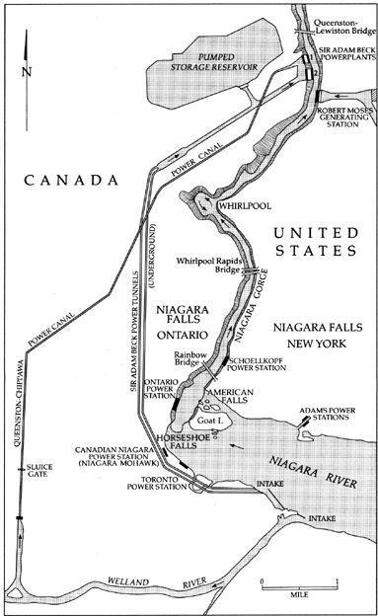

The boldness of the job fitted the chairman’s own personality. From an intake two miles above the Falls, Hydro was blasting the largest underground waterway in the world – a tunnel, five and a half miles long, three hundred feet underneath the town of Niagara Falls. At the lower end of the tunnel the water would race into a two-and-a-quarter-mile canal, constructed in a vast cut two hundred feet wide and ninety feet deep, blasted out of the rock. The other statistics were, as usual, breathtaking. The commission was planning forty miles of new roads. A new community, known as Hydro City, would house 3,000 of the 6,700 workers needed to finish the job. An artificial lake would be gouged out of a 750-acre farm to serve as a reservoir. This, in effect, would act as a storage battery, holding surplus water drained from the river during off-hours for use during the day when the Falls needed more water for tourist viewing.

Power canals on the Canadian side

This wasn’t enough for Saunders. During the first week of June, 1951, he announced that a second tunnel, also five and a half miles long and more than fifty feet across, would be blasted from the rock to run alongside the original cut to develop an additional half-million horsepower for the Beck 2 plant.

There were other headlines that week, however, that stole the spotlight from the publicity-conscious Saunders. The arrival of Marilyn Monroe and a Hollywood film company served as a lively entr’acte played before the curtain of the more serious drama of power and politics.

Monroe was then on the verge of super stardom. Niagara Falls rocketed her to the pinnacle. The great cataract served as a backdrop for a brief scene that made screen history and provided the actress with a trademark so recognizable, so individual, that Marilyn impersonators still use it to hook their audiences.

The movie, of course, was

Niagara

. It co-starred Joseph Cotten and Jean Peters but was tailored specifically for Monroe. Many an actress has walked into stardom, but, as has been said, she succeeded by walking

away

from it. Henry Hathaway, the director, photographed her as no one else had, but it was the famous, voluptuous “Marilyn walk” that made screen history.

A special track was laid for the scene, which was shot from the site of Table Rock. Dressed in a skin-tight black skirt and a flaming red blouse, the actress alighted from a car and wriggled her way for 116 feet through what has been called “the longest, most luxuriated walk in film history.” Hathaway shot the scene from behind.

“Mr. Hathaway told me I swerved too much,” Marilyn remarked with calculated innocence. “Those damned cobble stones are hell to walk on in high heels.” But the damned Niagara cobblestones helped to tum her into a Hollywood icon.

Marilyn Monroe’s fortnight at the Falls has become part of her growing legend. Sequestered in the General Brock Hotel, and under orders from Hathaway to give no interviews, she unwittingly contributed to the Honeymoon Capital’s mystique by managing to conduct two love affairs while making the film. Her longtime friend Bob Slatzer succeeded in renting an adjoining room in the already overcrowded hotel. There, with the Falls thundering just outside the window, he proposed marriage, and she accepted.

The great cataract’s magic did not long endure. Marilyn left Niagara Falls on June 18 and married Slatzer in Tijuana, Mexico – a union that lasted just four days. Later she became the wife of Joe DiMaggio, who had also flown to the Falls to be with her.

When

Niagara

was previewed the following year at the Falls, hundreds of people wrote demanding rooms at the “Rainbow Motel” featured in the movie. There was, of course, no Rainbow Motel. It had been no more than a false front built in a strategic position so that the Falls could be seen in the background. No actual motel, at that time, met the director’s requirements.

Ontario, meanwhile was pushing ahead with its newest hydroelectric development almost as fast as Hollywood made films. Hydro was not hampered, as Moses was, by a clause in the international treaty providing that Congress would have the final say in determining which agency would develop the U.S. share of the Niagara power. That simple statement, added to the treaty at American insistence, was to delay the project for the best part of a decade.

The five major private utilities waged what President Harry Truman called “one of the most vicious propaganda campaigns in history” to keep the project in their own hands. Their purpose was to portray the “power socialists,” as the chairman of Consolidated Edison called them, as captives of a foreign philosophy. Ernest R. Acker, president of Central Hudson Gas and Electric, made no bones about it. “We have conducted a vigorous campaign,” he said, “to present to the people the dangers of the ‘creeping socialism’ which is inherent in the proposals of the public power advocates.” The campaign had many powerful supporters, including eight major farm organizations. The New York Chamber of Commerce and the powerful General Electric Corporation took full-page newspaper advertisements to publicize their cause.

The advocates of public power were divided, and that added to the delays. Should army engineers build the plant, as a bill before Congress proposed? Or should the New York State Power Authority do the job, as another urged?

In 1953, a year before the Moses appointment, the House of Representatives Committee on Public Works shelved both bills and opted for one urging private development. It passed the House, but before the Senate could vote, Governor Dewey jumped into the fight on the side of public power, which, as he pointed out, the state of New York had been advocating for almost half a century. “If this is creeping socialism,” Dewey said, “then it did its creeping forty years ago.” The bill was set aside.

The following February, however, Dewey himself bridled at a new bill authorizing New York State to build the powerplant but without federal funding. This bill would have given municipalities and co-operatively owned utilities preference over the private companies in power distribution. Dewey, who faced a rift in his own party when a Buffalo senator denounced his proposals as “pure unadulterated socialism,” backtracked. In a remarkable piece of Cold War rhetoric, he declared that there should be no coddling of “those communities which bend the knee to the Moscow concept, abandon private operation of their public utilities, and socialize them.”