Niagara: A History of the Falls (57 page)

Read Niagara: A History of the Falls Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

It is then that a shiver runs down the spine as the visitor realizes that all the windows are boarded up, the eaves troughs are crumbling, the paint is peeling, the front porches are falling apart. Here and there, behind an unprotected and shattered window, the remnants of an old Venetian blind hang limply. And above each doorway a naked light bulb bums day and night, a wan message that the house has been abandoned.

It is an eerie sight, this suburban ghost town. Block after block, the spectacle is the same. Three hundred acres that were once home to twenty-six hundred men, women, and children lie deserted. We are familiar with films and photographs of abandoned mining camps and false-fronted cow towns. But this is not the Old West. This is modem America. Is the shape of things to come to be found here within earshot of the continent’s greatest natural wonder? Already another community some three miles away – Forest Glen – has had to be abandoned for similar reasons.

Love Canal is still not free of controversy. People are moving back into the outer ring of homes, two hundred of which were put up for sale by the revitalization agency after a federal survey in 1988 deemed them “habitable.” By the spring of 1992, thirty had been sold. But what does “habitable” mean? Only that these houses are no worse off than comparable housing elsewhere in Niagara Falls. For Lois Gibbs, still fighting the environmental battle from her new base outside Washington, that does not mean the houses are free of risk. Even as the new tenants moved in, her organization and several others were planning court action to force a study.

Suits and countersuits drag on. Occidental, which has paid $20 million to 1,328 plaintiffs as the result of a class-action suit, is suing the state, the city, and the school board for funds to help pay the costs of a clean-up. The total cost of litigation has been estimated at $700 million.

This may be only the beginning. The empty homes with their naked light bulbs stand as testimony to the great dilemma of our times: what to do with the unwanted by-products of industry? The problem extends far beyond those ghostly streets. After Love Canal, three more Hooker dumps in the Niagara Falls area were identified, each much larger than the original. Together these alone contain a million tons of waste products. Thanks to the Love Canal controversy, the industries along the river have been cleaned up; they no longer discharge their wastes into the Niagara. But the old dumps remain, some unidentified because no one can remember where the truck-loads of poison were taken decades ago. There are an estimated 250 of these trouble spots within three miles of the river. To find them, excavate them, and remove their contents represents a herculean and hideously expensive task.

The great cataract has become a victim of its own immensity. Its spectacular presence alone was never enough to satisfy those who sought to transform it into a theatrical backdrop for high carnival or to harness its apparently limitless energy to banish industrial grime. The Falls proved a fickle servant. It was that same energy – captured by man, channelled and transformed – that powered the chemical revolution that defiled Niagara’s waters. Those early pioneers who talked so enthusiastically of the genie in the bottle did not live to see the havoc caused after the genie escaped.

How bitterly ironic that 89 percent of the pollution that is leached into the Niagara comes from the American side and not from the side show on the opposite shore! Those early pioneers – Porter and Evershed, Schoellkopf and Adams – could not know that the by-products of their vision would some day defile the river. Their purpose was laudable enough – to separate the great cataract from the beneficiaries of its power, to create an industrial community that did not encroach upon the glory of the Falls. The result is Buffalo Avenue, that crowded chemical alley of squat factories and high-tension pylons that leads from the Love Canal area to the business centre of the city. Buffalo Avenue is to Niagara Falls, New York, what Clifton Hill is to Niagara Falls, Ontario. But the much-maligned hill, for all its tinsel glitter, does not befoul the waters.

Yet there is one crowning glory that remains, and it is to be found on the American side. Goat Island continues to provide a haven from the industrial world as it has since the days when Augustus Porter saved it from commercial exploitation. The manicured park land and the encircling roadway of the state reservation are encroaching upon the wild, but thanks to men like Olmsted and Church, some of the original forest remains and visitors can enjoy the kind of ramble in the woods that helped spark the preservation movement of the last century.

Well away from the tourist routes is one little glade where commerce does not intrude. Just opposite little Luna Island on the eastern bank of Goat Island beneath a canopy of birch, black willow, and shagbark hickory, a narrow pathway meanders along the water’s edge. Here, beside the slenderest of Niagara’s channels, the workaday world is blotted out. The cataract’s roar and the hiss of the rapids, racing over the limestone ledges, blur the stridence of the twentieth century. The soft curtain of foliage conceals the jagged silhouette of the skyline beyond.

Here is the peace that Francis Abbott sought. One can easily imagine him in his brown cloak, with his dog by his side, lounging on this very spot and staring into the violent waters at his feet, calmed by the tranquillity of the forest yet haunted by the magnetic pull of the river on its final rush to the brink. Did he shudder a little at the power and treachery of the Niagara River and the Falls beyond? Or did he simply surrender himself to their sorcery? Beauty, danger, terror, and charm are here combined. Over the centuries, poets, essayists, historians, and ordinary visitors have struggled, and often failed, to find words to describe the lure of these waters. Yet in the end, a single word – an old, well-used word – best captures the essence of Niagara. In spite of mankind’s follies and nature’s ravages, in spite of scientific intrusion and unexpected catastrophe, in spite of human ambition and catchpenny artifice, the great cataract remains what it has always been, and in the true sense of the word, Sublime.

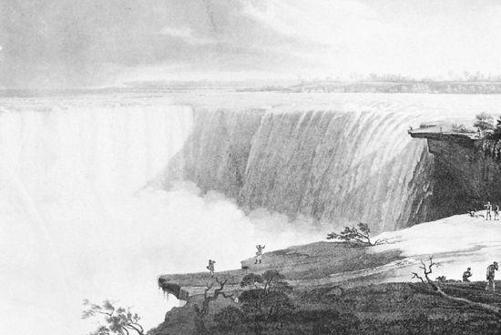

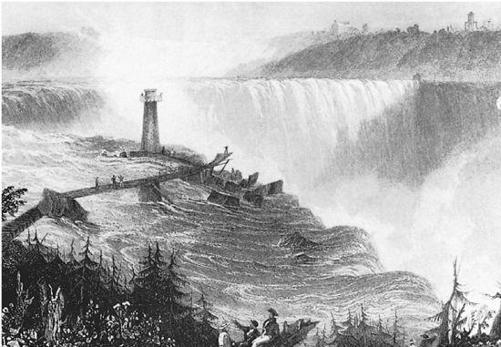

The Falls, with Table Rock in the background, right, engraved from a painting by John Vanderlyn in 1803 when the flow of water over the precipice was twice as great as it is today.

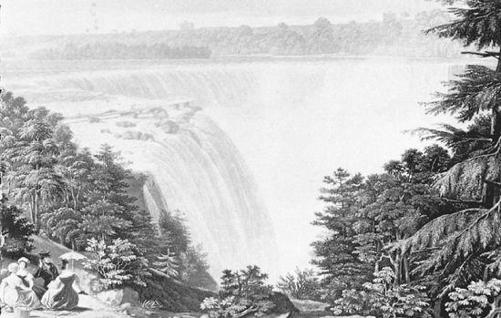

The Horseshoe Falls from Goat Island, painted in 1830. Note the precarious bridge to the Terrapin Rocks just above the crest.

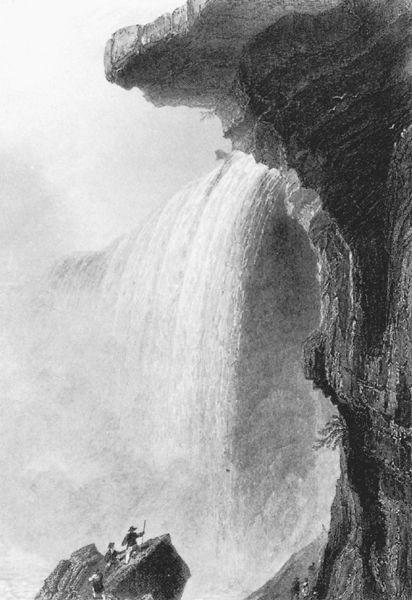

W.H. Bartlett, the much-reproduced artist of

American Scenery

and

Canadian Scenery

, sketched the massive overhang of Table Rock in 1837.

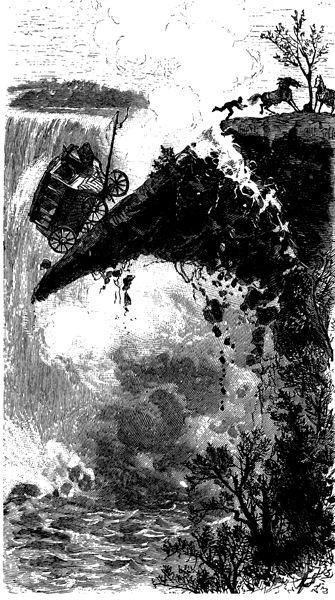

The fall of Table Rock in 1850. The hackman, washing his Carriage, barely escaped when the dolostone cap crumbled.

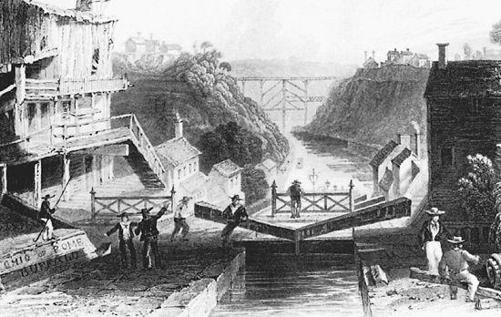

One of the locks on the Erie Canal, which helped turn Niagara Falls into a fashionable spa, rivalling Saratoga Springs.

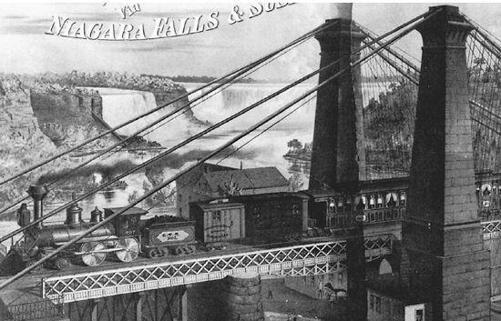

Like the drawing above, this one was made in 1837 by Bartlett for

American Scenery

. It shows the Terrapin Rocks, Tower, and bridge.