Niagara: A History of the Falls (53 page)

Read Niagara: A History of the Falls Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Once again, man had tried to change the course of nature. This time nature was to be allowed to take its own course.

Chapter Thirteen

1

Love Canal makes the news

2

The mother instinct

3

The long crusade of Lois Gibbs

4

Taking hostages

1

Love Canal makes the news

Five years after the American Falls International Board agreed not to tamper with nature, Niagara Falls, New York, was plunged into the worst crisis in its history. The earlier prophecies of trouble at the old Hooker Chemical dump in the Love Canal returned to haunt the city. For well over a century, the Falls had enjoyed an international reputation as a glamorous and spectacular resort. By 1978 that reputation was tarnished.

By shutting off the American Falls almost as easily, it seemed, as turning off a kitchen tap, man had “conquered” Niagara. Decade by decade, more and more water rushing toward the cataract had been taken to produce power. But much of that power had been used to fuel the factories where ordinary carbon was transformed into a satanic mixture that now bubbled up in the basements of families that had bought houses near 97th and 99th streets in the LaSalle residential district of the American city. (There was no 98th Street. That was the site of the Love Canal.)

In 1976, after one of the heaviest snowfalls in history, the situation had become critical. Several years of abundant snow and rain had already turned the old canal into a sponge. Its contents, often disturbed by digging, were overflowing into the surrounding clay and sandy loam, oozing through the old creekbeds and swales that formed swampy channels extending into the neighbourhood. That year, Patricia Bulka discovered a black, oily sludge oozing out of the drains into her basement. Her mind turned back to ten years earlier, when she and her family had moved into the LaSalle district in the southeast corner of the city. Her son Joey had fallen into a muddy ditch, and when his brother, John, pulled him out, both boys came home covered in what she described as an “oily gook.” She scrubbed them down and threw their clothes away, but the noxious odour from the muck filled their house for more than two weeks.

At that time, Mrs. Bulka had alerted the Niagara County Health Department. Men arrived, took soil samples, and assured the Bulkas that nothing was wrong. Afterwards, Mrs. Bulka had to endure the indignation of the neighbours, some of whom refused to speak to her for calling the authorities and, by implication, threatening the real-estate values in LaSalle.

Thereafter, Patricia Bulka held her tongue. If she connected young Joey’s chronic ear ailment or John’s respiratory problems with the incident, she said nothing, even though both problems had begun after the boys went into the ditch. But in the spring and summer of 1976, she found that her neighbours also had basements redolent with the same oily black sludge that was welling up in hers. The Bulkas bought a sump-pump to clear their basement; so did several of their neighbours.

Nobody now attacked Mrs. Bulka for her concerns. Calls began to flow in to the Niagara Falls

Gazette

, which sent its educational reporter, David Pollak, out to the LaSalle district to look into the complaints. On October 3, Pollak reported that “Civilization has crept to the doorstep of a former Hooker Chemicals and Plastics Corp. waste deposit site, and the combination contains the elements of an industrial horror story.” The phrasing was melodramatic, but, as it turned out, Pollak had not exaggerated the situation.

Over the past year the Bulka family had worn out three sump-pumps trying to cope with the seepage through cellar walls that were only one hundred feet from the dump site. Pollak had some of this material analysed by an independent firm. Its analysis made it clear that the chemical content came from Hooker wastes. Love Canal, the

Gazette

reported, contained at least fifteen organic chemicals including three chlorinated hydrocarbons, which, the analysts declared, constituted an “environmental concern” and were “certainly … a health hazard.” Anyone who breathed the fumes or touched the substances could be affected. The only immediate action taken by the county health department as a result of these revelations was to state that sump-pumping was illegal and to threaten to take action against anyone pumping out a basement into the sewer system.

Meanwhile, the winter of 1976-77 dragged on, leaving the residents worrying about a problem the authorities refused to acknowledge. The odours abated during the cold weather but returned in the spring. George Amery of the county health department assured everybody that while the fumes might be disagreeable, they posed no immediate health threat to the people living along the old canal. By May 1977 the seepage had been found in at least twenty-one homes. The state ordered corrective action, and in June, the city commissioned a private corporation to study the problem and come up with a solution. Nothing more was heard from officialdom about Love Canal until August, when a dogged reporter, Michael Brown, dug into the human side of the story and sparked the protest movement that, in the end, made Love Canal a byword for pollution in North America.

Brown, a published author, had been bom and raised in Niagara Falls. Returning after a five-year absence in 1975, he found a new spirit in the community. Local politicians were proudly announcing handsome new industrial and office buildings. The city seemed to be getting back on its feet after a long decline. In February 1977, Brown went to work for the

Gazette

as a suburban reporter. That summer, he covered a public hearing concerning the existence of a waste disposal firm in the city. A young woman took over the microphone to oppose the company’s presence and suddenly, to Brown’s mystification, burst into tears as she mentioned another dumpsite ravaging her neighbourhood. That was the first Brown had ever heard of Love Canal. He went to the

Gazette

library and dug out the Pollak articles and some other clippings. Except for Pollak’s investigation, the reports were reassuring. The consensus seemed to be that the situation was well in hand, and there was little hard fact to support the young woman’s emotional outburst.

He soon changed his mind when he visited the Love Canal area. As he wrote later, “I saw homes where dogs had lost their fur. I saw children with various birth defects. I saw entire families in inexplicably poor health. When I walked on the Love Canal, I gasped for air as my lungs heaved in fits of wheezing. My eyes burned. There was a sour taste in my mouth.”

On August 10, Brown wrote his first front-page story, the opening shot in a crusade that would win him a Pulitzer Prize. The state ordered the city to investigate, but when the city found that corrective action would cost $400,000, it rejected it as too expensive. That was a short-sighted decision; within a year the bill for temporary remedies would soar to $2 million. (The total cost of cleanup was later put at $500 million.)

Assured that the story would be pursued, Brown returned to his suburban beat. But the newspaper, under heavy pressure from city officials and industrial leaders, played the story down. “There seemed to be an unwritten law that a reporter did not attack or otherwise fluster the Hooker executives,” Brown later wrote. Nothing more appeared in the press until February 1978, after Brown was given the city hall beat. On February 2, in his Cityscape column, he charged, “Government officials are in the throes of a full-fledged environmental crisis.” The city was supposed to take action the previous summer, he wrote, but nothing had been done.

By this time the filled-in land over the canal between 97th and 99th streets was a quagmire of greasy mud and potholes. When a city truck tried to cross the field to dump clay into a hole, it sank to its axles. In May, after David Pollak was made city editor, the

Gazette

stepped up its coverage. This wasn’t easy because the authorities kept a tight lid on information. The Environmental Protection Agency had at last been persuaded to conduct tests in the basements of the houses on the canal to see if chemicals were present in the air. It took Brown three months to get at the results, which had not been published. A stray memo to a local senator revealed that benzene had been detected on the streets adjoining the canal. This widely used solvent is a carcinogen known to cause headaches, fatigue, weight loss, dizziness, and, eventually, nosebleeds in addition to damage to the bone marrow. The toxic vapours, the EPA survey reported, “suggest a serious threat to health and welfare.”

Brown kept up the exposés. He revealed that both federal and state officials were considering declaring Love Canal a disaster area and evacuating some residents. He quoted a state biologist as saying that if he owned a home near the canal and could afford to move, he would. That same month – May 1978 – the state announced at last that it would conduct a health survey based on blood samples taken at the southerly end of the canal area. The results were alarming. The women living in the area had suffered a high rate of miscarriage and given birth to an extraordinary number of children with birth defects. In one age group, 35.3 percent had records of spontaneous abortion – far in excess of the national average. And the people who had lived for the longest period near Love Canal had suffered the highest rates.

It was about this time that a slender, dark-haired housewife named Lois Gibbs found herself involved. She was only twenty-six, painfully shy, politically uncommitted. Love Canal would change her life forever, as it changed the lives of so many others in Niagara Falls, New York.

2

The mother instinct

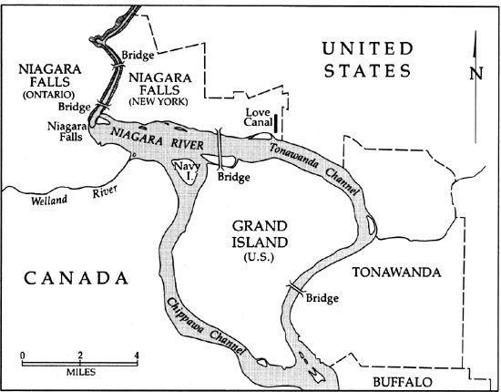

Lois Gibbs had been born and raised on Grand Island, some three miles above the Falls. She married young, as most of her friends did, and after her son, Michael, was bom in August 1972, the family moved across to the city so that Lois’s husband, Harry, would be closer to his job as a chemical worker at Goodyear Tire.

Grand Island

They bought a three-bedroom house on 101st Street, three blocks south of Love Canal. Mrs. Gibbs had been only vaguely aware of Mike Brown’s stories in the

Gazette

and was confused by his references to 97th and 99th streets. These streets came to an end at Pine Avenue (now Niagara Falls Parkway) and commenced again farther to the north. She thought the problem lay some distance away on the far side of Pine. Though she sympathized with the people whose property seemed to be contaminated, she did not connect the problem with her own district until Brown mentioned the 99th Street School. That brought her up short. “Wow!” she thought. “This isn’t on the other side of Pine Avenue. This is in my own backyard.”

She called her brother-in-law, a professor of biochemistry at the state university in Buffalo, and asked him to translate some of the scientific jargon in the articles. She couldn’t quite believe what he told her. It was enough, however, to convince her she should get her son out of the school. She went to the

Gazette

library to read the back files. From these she learned that some of the chemicals could cause a nervous reaction while others might cause blood disease or leukemia.

Lois Gibbs was suddenly very alert. Since Michael had started school the year before, his blood count had gone down and he had begun to have seizures. She had been vainly badgering her pediatrician about her son’s condition, which he had diagnosed as epilepsy. Now she began to suspect that there might be another cause.

She reproached herself for her earlier inattention: “God! It’s all my fault.” Until now she had thought of the grassy expanse that covered the old canal as nothing more than a little park in which her children could gambol. Before Michael started school she had been in the habit of taking him and his younger sister, Melissa, there every day before lunch –

every

day, because, as she was to recall, “being a blue-collar Mom, you have a routine and you never vary it.”

Up to this point, Lois Gibbs was, as she herself later remarked, “a typical blue-collar housewife.” Her husband was employed on shiftwork at Goodyear. Her own life revolved around the home. As she was to put it, “when you graduate from high school you get married, you have children, the boys go bowling and go for a beer Friday night to cash their checks, and the girls do Bingo with Mom.” She didn’t belong to any community organizations, had no interest in politics, and voted Democrat only because her mother did. She was a private, inward person, so shy that she mailed in her city taxes rather than paying the bill personally, as others did, because she didn’t want to face strangers at the counter.

That is the unlikely background of the woman who achieved international attention as the determined and effective leader of the activist movement that forced a mass evacuation of the Love Canal district.