Nolo's Essential Guide to Buying Your First Home (23 page)

Read Nolo's Essential Guide to Buying Your First Home Online

Authors: Ilona Bray,Alayna Schroeder,Marcia Stewart

Tags: #Law, #Business & Economics, #House buying, #Property, #Real Estate

BOOK: Nolo's Essential Guide to Buying Your First Home

13.62Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

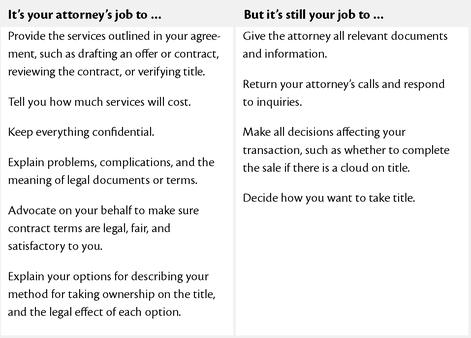

Who Does What

Sometimes, a homebuyer goes directly to a lender, rather than dealing with a mortgage broker. The buyer may like the personal aspect of walking into a local bank branch or even have found a better deal than is available through a broker. You can often find a lender’s advertised rates on the Web or in your local newspaper—we’ll talk about searching for that in Chapter 6.

If you decide to work with a lender, you’ll probably still be dealing primarily with a person within the institution called a “mortgage banker” or “loan officer.” This person performs the same duties (more or less) as a mortgage broker, except that instead of scouring the entire loan market, the loan officer will help you identify which of the bank’s own portfolio of loan products suits your needs. In other words, you’ll be limited to the loan packages offered by that institution.

The loan officer should help you fill out your application and handle necessary paperwork like obtaining your credit report and getting an appraisal. However, once you’ve chosen a bank, you won’t be able to choose your loan officer as you would a broker—or your available choices will be limited.

How much personal contact you have with a specific loan officer depends on the lender. Lenders come in all shapes and sizes, from the behemoth bank to the local credit union. Some operate almost entirely online, even having you apply online. These lenders may be keeping their overhead low by cutting out the operating costs of the local office, passing the savings on to you. If you work with online lenders, you’ll have to rely more heavily on technology (email, fax machines, and scanners) to transmit documents. You may also have to accept that you’ll never meet the loan officer face to face or that you’ll be dealing with several different people during the transaction.

Your Fine Print Reader: The Real Estate AttorneyIn some states, real estate attorneys are a regular part of the homebuying process. Even in states where this isn’t the case, a complex transaction may need an attorney’s assistance. After all, if you don’t use an attorney and the transaction later goes awry, you’ll still have to hire one, at much greater time and cost. Save yourself the headache by working with a lawyer to structure the deal, not salvage it.

TIPThere’s no substitute for your own attorney.

Don’t expect the seller’s attorney, the closing agent (who may be an attorney), the real estate agent, the mortgage broker, or anyone else in the transaction to look after your legal interests.

A real estate attorney is, by definition, one who focuses on real estate transactions. This may sounds obvious, but you don’t want to get stuck working with an attorney whose main expertise is estate planning or corporate mergers. Ideally, your attorney will have several years of real estate law experience, at least some of it working directly with other, more experienced attorneys. Additionally, in most cases, you’ll want an attorney who specializes in helping buyers with their residential real estate transactions: drawing up contracts, researching title, and the like. An attorney who specializes in litigating disputes is a better fit if you think you’ll need to sue or you might be sued—but when structuring your deal, you’ll be trying to avoid that result.

CHECK IT OUTAre attorneys always involved in real estate transactions in your state?

Any experienced real estate agent should be able to tell you this right away, but you can also check with your state bar association. Find it through the American Bar Association’s website at

www.abanet.org/barserv

(under “Find a local, state, or specialty bar association”).

Depending on your needs and which state you’re in, your attorney may become involved in one or more of the following: negotiating, creating, or reviewing the sales contract; overseeing the homebuying process to check for compliance with all terms and conditions of the contract; performing a title search or reviewing the title abstract or title insurance commitment (to determine whether there are any liens or encumbrances on the property); explaining the effect of any easements or use restrictions; negotiating or representing you in a contract dispute with the seller; and representing you at the closing.

TIPCheck your prepaid legal plan.

Such plans may provide legal services for homebuyers, so if you have one, this may be the time to use it.

An attorney can also assist you in complex transactions, for example if:

Getting the Best Attorney Out There• Legal claims have been made against your prospective house that must be satisfied by the time the property is sold.

• Problems show up with the title: for example, the driveway is shared by the house you want to buy and the neighboring house, but that isn’t reflected in the title.

• You need help reviewing community interest development agreements and documents like CC&Rs, a co-op proprietary lease, or a new home contract drafted by the developer.

• You need to structure a private loan from a relative or friend to make the purchase.

• You purchase the house jointly with others and need to structure a cobuyer agreement and document how title will be held.

You may be tempted to get the cheapest attorney you can, but it’s smarter to get one who’s a real estate expert, even if it costs more. If you pay the attorney by the hour, the seasoned one will take less time than, for example, a criminal defense lawyer, who’ll need to spend time just researching real estate laws.

Many, but not all, states require you to have a written fee agreement with your lawyer. It’s worth doing, anyway. Your agreement establishes the terms of representation: what the lawyer is expected to do, how much you’ll pay and on what basis (for example, hourly or a flat rate), and when the lawyer must be paid. Often you’ll have to pay some advance money, called a retainer—but the rest of the lawyer’s fee will be paid later.

TIPCount the hours.

If you have an hourly arrangement with your attorney, here’s a way to keep costs in check: Ask that the attorney contact you before starting each discrete task (like reviewing condo CC&Rs) and give you an estimate of how long that task will take. If it sounds reasonable, say okay, but require the attorney to contact you if additional time is needed.

To find potential attorneys, get recommendations from friends, coworkers, and trusted real estate professionals. While you can check with professional organizations or use lawyer referral services, these systems suffer from the same problems as with other professions: Other than membership, you have no real way to gauge the person’s effectiveness.

Then interview three or four attorneys. Clarify in advance whether you must pay for this interview time. Some attorneys offer free consultations, others don’t. It may be worth paying, though, to start your case off with a highly regarded attorney. At the interview, ask about not only the attorney’s general legal skills, but also how much time he or she spends on transactions similar to yours—especially if you’re buying a condo, co-op, or newly built house.

If possible, get and check references for any attorney you plan to hire, especially if a substantial amount of legal work (and money) is involved. While some attorneys will be reluctant to provide names of clients (because of client confidentiality), it doesn’t hurt to ask.

Who Does What

Other books

Three to Get Deadly by Janet Evanovich

Shoot to Kill by Brett Halliday

A Cleansing of Souls by Stuart Ayris

River Of Fire by Mary Jo Putney

House Rules: The Jack Gordon Story by Liz Crowe

Against Gravity by Gary Gibson

Scattered by Malcolm Knox

Taking a Chance by Eviant

All Things Wicked by Karina Cooper